The Broken Bird? Notes on the Unsolved Mystery of the Loon’s Name

Sarah Harlan-Haughey

“There’s a large bird lying on the beach with its legs broken—what can I do?”

Wildlife helpline call centers in Florida routinely respond to this kind of call—the concerned caller has often encountered a stranded Common Loon, or Gavia immer. Loons have heavy bones—they haven’t the airy mesh of trussed marrow common to most other flying birds. Their bones are solid straight through, like those of the cormorant and penguin—likewise thick, oily diving birds—and their legs project back from the very end of their abdomen, an arrangement that is a great boon for propulsion through water, but which makes walking on land well-nigh impossible. Loons can wiggle themselves awkwardly forward on their breast bones, but the sight is pathetic: “the bird flounders along on all fours.”[1] Heavy bones pulling down its massive breast, legs splayed out behind it, froglike, its attempts to lift and move itself would be laughable if they didn’t remind the ecologically traumatized modern watcher so forcibly of commercially raised chickens. Indeed, the comparison is unsettling; the loon’s movements on land do resemble those of massive Middle-American factories’ chickens: struggling to lift their doomed bodies for a moment from the ground, walking for a few steps, then crashing back down.[2]

“No animal has evolved to deal with the Anthropocene, not even us.”

Contrary to disturbing appearances, the loon-birds are often not stranded at all—many simply wait on the beach, exhausted from their long flight south from northern lakes, resting for an hour or two as the tide comes in to carry them out to their watery element. But some are; some mistake large parking lots, roads, and other manmade structures for bodies of water. And once they have landed—think of a loon like an airplane, as it needs a lot of runway for takeoff and landing—they cannot get airborne again on their false pond and must await a fate of starvation, dehydration, predation, or vehicular crushing.

The loon’s brain is not built for carparks. It’s funny how often we must remind ourselves of this basic fact whenever a deer “stupidly” vacillates on a highway or a sparrow breaks its neck on a window. No animal has evolved to deal with the Anthropocene, not even us. But a loon’s ancestral memory is older even than that of the sparrow or the deer. The loon has existed—like the shark and the crocodile—in basically the same form since birds first moved on this planet. Its consciousness is Cretaceous. It was shaped by a pre-human, watery world, [3] and our innovations confuse it. It may be an efficient machine, but it can’t take flight from asphalt. It needs great bodies of water to take off—and when aloft, its wingbeats are heavy, louder than other birds’ of the same size, and somewhat laboring. Flying, it holds its head lower than other long necked birds, as if drooping with exhaustion.

So, these broken-legged birds, they’ve shed their summer coat—that gorgeous geometric dappling of white squares and checks, a triangular, white-striped collar, a luxurious mantle of glossy black—for a nondescript grey cloak, the uniform of the seabird. But their oval red eyes remain, those wild eyes! And the birds themselves are so large, so solid! So placid as they sit, grounded, waiting. Some make it into the warm Gulf and Atlantic waters, others may be harried to death by dogs or people. Helpless? Disabled? Loony?

The word loon is a contested one. No one seems completely sure where or when it came from, and what it means. But there is no doubt that the story and vocabulary of human disability is often entangled in the story of our interactions with these birds—the name is often conflated with other homophones or near homophones that align with our perception of these creatures as crazy, crippled, depressed, or otherwise challenged.

I suspect we kept the loon’s name partly because we felt it fit this denizen of the great “howling waste” of North America. It embodies the wilderness for many, as Thoreau shows in his famous description:

“The loon uttered a long-drawn unearthly howl, probably more like that of a wolf than any bird, as when a beast puts his muzzle to the ground and deliberately howls. This was his looning, perhaps the wildest sound that is ever heard here, making the woods ring far and wide.”[6]

The howl is singular, and wild, but it is not the only strange and moving vocalization of this waterbird. Indeed, the loon abounds in sound. Oliver Austin, the author of the beloved Birds of the World, notes:

“It embodies the very spirit of far places, of forest-clad lakes where the clear air is scented with balsam and fir . . . no one who has ever heard the diver`s music, the mournful far-carrying call notes and the uninhibited, cacophonous, crazy laughter, can ever forget it.”[7]

A goofy giggling cackle, the tremolo, is one of the most distinctive vocalizations of the Common Loon, next to its wail. The sound is cracked, silly, insane—Thoreau’s “demoniac laughter.”[8] One homophone that existed alongside the word loon or loom starting in the late Middle English period (a very fertile period of linguistic borrowing) and almost certainly interacted with it was the Dutch word loen or lowen, glossed by the editors of the OED as “homo stupidus.”[9] When Macbeth furiously ejaculates, “the Devil damn thee black, thou cream-faced loon” he is not insulting his servant by calling him a mad, strange waterbird (though Shakespeare cunningly bumps the other loon against this one by association, by invoking a goose in the next line[10]) but rather a knave, or “boy” in the pejorative sense—i.e. a useless youth, a layabout, a young fool with more hormones than sense perhaps.

“There is a seemingly ancient connection between this wilder-than-wild bird and the deep night, as will remember anyone who has slept on the shore of a northern lake and heard the long plaintive cry of a loon calling out to her mate and the reply echoing across the still water under the stars”

Beyond being a lout, a loon is also a madman! Many are familiar with the origin of the epithet loon, or the adjective looney to describe someone who isn’t quite right in the head. A human loon is a lunatic—someone overly influenced by the phases of the moon.[11] And here is where one of the most tenacious folk etymologies (that is, etymologies that are based on intuition or association, not methodical or accurate philological research) for the Common Loon arose; there is a seemingly ancient connection between this wilder-than-wild bird and the deep night, as will remember anyone who has slept on the shore of a northern lake and heard the long plaintive cry of a loon calling out to her mate and the reply echoing across the still water under the stars. We sense a deep link between this grand black bird, the starshine and the moonlight, the lapping waters of a cold lake, and a certain emotion—not fear, not insanity, not a sublime joy, but something with a little bit of all three mixed in. This is a rarefied emotion that only the ancient call of the loon (and also wild canids) can arouse in the human heart.The correspondence between loons and lunacy is too fitting and evocative, and sometimes etymological theories are too pleasing to set aside. (Just ask Isidore of Seville, originator of many such delightful folk etymologies. Consider, for example this charming theory: ‘The walking stick (baculus) is said to have been invented by Bacchus, the discoverer of the grape vine, so that people affected by wine might be supported by it,’ or that.”[13] Similarly a horse is an equus because it is balanced (aequare) when one hitches up a team of four.[14] These etymologies may be strictly “wrong,” but on some poetic level they make sense.)

I think it is fitting it that children all over the North Woods are taught, however erroneously, that the loon is called a loon because it is loony, singing its “looney” tunes to the moon in the dark of the night. It is somehow appropriate that that spine-tingling howl—a call to question one’s own ontology, and to think about the meaning and origins of things—is associated with an intellectual call to also delve into older layers of human language and culture. After all, the call of the loon is the siren’s call to “civilized” humans to some atavistic knowledge we have forgotten to remember. The way this bird makes us feel somehow more wild, less human. This is a satisfying name-story.

So: the madness of the lunatic, the idiocy and clumsiness of the loen—these aren’t close matches, though they linked up through homophonic analogy and folk etymology with the great black bird over the centuries.[15] So: where did the word come from? Let it be equally fitting, equally illuminating of our strange relationship with this marvelous bird! Most popular etymologies, and even the incomparable Oxford English Dictionary, note that the word loon or loom originates in the language of the Norsemen, in the Old Norse lómr, perhaps meaning something like “lame”—disability again![16] These editors believe it refers, presumably, to the loon’s inability to move very successfully on dry land.[17] The Norse word lama, loma, or lame (meaning “disabled in the limbs, maimed, crippled, weak, paralysed, palsied) has a cognate in the related West-Germanic language of Old English, lumme, and both arguably entered the English language in many forms.[18] Consider lumme/lama’s legacy in our modern lame, and possibly loon, but arguably also in the now archaic but somehow onomatopoetic lummox, a word that so evocatively describes an awkward or idiotic person (in the words of the OED, “A large, heavy, or clumsy person; an ungainly or stupid lout.”)—again, back to the loen analogue.[19]

The complex of loom/loon words in the Germanic languages offer a maddening philological puzzle. The Old English word lumme and its cousin, the Old Norse word lama, which become our modern lame, are related in turn to the loom, the weaving tool, lump, lame. These are words for stuff, words to describe things happening, words to describe objects and tools, etc. In short, this is a great puzzle of historical linguistics and one I am not equipped to solve, but I’ll cut to what I understand to be the chase. The Indo-Europeans, those romantic ancestors of so many Eurasians, those ancient people who spoke the language that would branch into Sanskrit, Persian, Latin, Greek, Irish, Russian, English, and many other languages living and dead—those chariot-drivers, horsey people of the steppes, sky-god worshippers—they had an ancient word that denoted brokenness, degrees of disassembly, or even at times just a pile of stuff, or materia—and that ancient word (the great historical linguist Anatoly Lieberman identifies the hypothetical Indo-European root as “*lam-/*lom- ‘broken’”) could well be the beginning of the word for the loon.[20] And that, of course, brings us back to the broken bird on the Florida beach.

Maybe diver is a truer name, something that honors the ways in which this creature is differently abled from us humans. The bird may seem clumsy, mad, foolish, but man, can it dive! Any lake visitor who has tried to approach a pair of promenading loons on a canoe or kayak wonders at the marvelous speed at which these wary birds can cock their heads downward and immerse themselves, snakelike, into the water, disappearing for minutes, and reappearing sometimes yards, even quarter-miles away.[21] The loon’s dense bones allow it to control its heaviness and flotation—it can hold its breath for ninety seconds, and if diving and swimming at great speed away from a threat isn’t enough to effect escape, the wily bird can breathe with just its beak outside the water, a kind of avian submarine, complete with a periscope—or maybe snorkel.

But then, there’s one more possibility in our etymological enigma: Old Norse also preserved an Indo-European root (lā) that refers to a kind of chatter or sustained sound like a wail or a mourning keening: it may appear in Old Norse as lómr, loon, creating a poetic metaphor “from the cry of these birds, a cry, lamentation.”[22] The historical linguist Eric Partridge gives us the fullest gloss of the Old Norse word in this light: to him, the loon, “a bird, is a variation of the synonym loom, of Scan origin: cf. ON lōmr, itself from echoic lō-, cf the lā- of L[atin] lātare, to bark,” or make similar nonverbal, repetitive sounds.[23] This word has cognates in other words like the Latin lamentare, which becomes our lament, the Germanic lull, which appears in Middle English, Middle Low German, and Middle Dutch, and even the Greek lalos-talkative.[24] The original Indo-European word was likely lal, or something like it, an imitative word that suggests ululation, the wordless cries of mourning, and the vocalization of animals.[25] If this is the ultimate origin of the word for the bird loon, then its name refers to its talkativeness, its tremolo and cackle, its wide vocabulary, and its wild mournful cries, not its lameness at all! But the etymologists are divided about which Indo-European root led to our modern word loon, and the mystery persists.

As historical linguists have noted, Loon is most directly a Norse word. Whether it originally referred to the loon’s wail or to his lameness, the word came to English-speakers most recently through the Old Norse-preserving linguistic cultures of the Orkneys and Shetlands, and the Old Norse poetic record preserves some visions of these birds that certainly belie their disabled name, however we spin its origins. Consider, for example, the powerful episode in the great medieval saga about Gisli Súrsson, where the doomed outlaw hero Gisli dreams in his underground dugout of his impending death. Two supernatural dream women (draumkönur) haunt him—perhaps norns, perhaps Valkyries, perhaps an angel and a devil, respectively—who bring him visions of the future and of his possible afterlife. One (the more pleasant, well-favored dream-woman) shows him a syncretic afterlife that sounds a little bit like Valhöll, with its booze, golden mead-halls, and lovely bedmates, and a little like the Christian Heaven—goodness and light—while the other, an aggressive, demonic, erotic creature, tortures him with weird sex and appears to him bathed in blood, sometimes wearing a bloody skullcap made of human skin. On the last night before his epic last stand and death, Gisli dreams not of two women, but of two giant loon-birds (possibly avatars of the dream-women?) that fight one another, covered in gore, as he tells his wife Auðr:

When we parted, flaxen goddess,

my ears rang with a sound

from my blood-hall’s realm

–and I poured the dwarf’s brew.

I, maker of the sword’s voice,

heard two loon birds fighting

and I knew that soon the dew

of bows would be descending (551-553). [26]

The medieval Icelandic skald who composed this verse certainly did not intend his audience to see the loon as a symbol of helplessness.

This bird has a fierce culture: dedicated and ferocious, it will kill its own offspring by relentlessly pecking it and pushing it into the water until the little creature starves or drowns, all to better ensure the survival of its more promising chick.[27] It will fight to the death, a flurry of wings and beaks, torn-out eyes and skin gashes, for the right to be the consort of its long-term mate.[28] It has a complex vocabulary that expresses the nuances of its desire, its alarm. It can winter on the wildest, coldest coasts in the world, not just places like the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean. It is a true waterbird—more oceanic, more watery, perhaps, than almost any other bird. It never leaves its element, except to lay. Broken is not the word for this fierce being.

“Loons are, famously, tragically, the canaries of the Northern Lakes. Their health, and more and more frequently, illness, death, and absence in the lakes, indicates the lakes’ level of pollution.”

But yet it is, and it is in such a deep way, in the way that we humans have named and renamed it through projection, through an empathetic layering of the vicissitudes of human life and disability onto the biology of this alien creature. And it is in that spooky ability language has to mirror a changing reality through near-magical and trans-historical coincidence, that that Indo-European name, broken, fits again. Loons are, famously, tragically, the canaries of the Northern Lakes. Their health, and more and more frequently, illness, death, and absence in the lakes, indicates the lakes’ level of pollution. They die of lead poisoning from lead pellets and lead sinkers and jigs used by sportsmen—near 50% of unnatural loon deaths are attributed to lead ingestion, and this is a slow, twitchy death of immobilization (lameness!) by degrees.[29] They die of mercury poisoning, perhaps an even more insidious form of pollution, since it lasts for generations. Loons with mercury poisoning are sluggish (lame!) and neglectful of their chicks and eggs (crazy!) and produce 40% fewer offspring. But even chicks that make it out of the more exposed eggs alive are much less likely to survive, as they bear their parents’ curse in their blood.[30] In other words, heavy metal paralysis and madness seems the sad irony of modern human impact on the loons’ habitat—we may have erroneously called these birds mad or lame through the centuries, but now we have fulfilled the ominous prophecy of their name. Loons also die of loss of food sources and habitat through development. Their eggs, laid in semi-aquatic nests lumped together on the muddy, reedy edge of their freshwater summer homes (the loons haul themselves out of the water only to lay and incubate in their reedy nests), are washed out and away by the wake of propellered boats zooming past, or even worse, stalking the loon to observe its vulnerable domestic arrangement. Loons are broken on parking lots, on roads—they are broken on the beach, and are broken by oil spills. They are our broken bird, and the Northern Lakes will not be the same if they go, these ancient denizens of this cold world. Cause for lamentation, indeed.

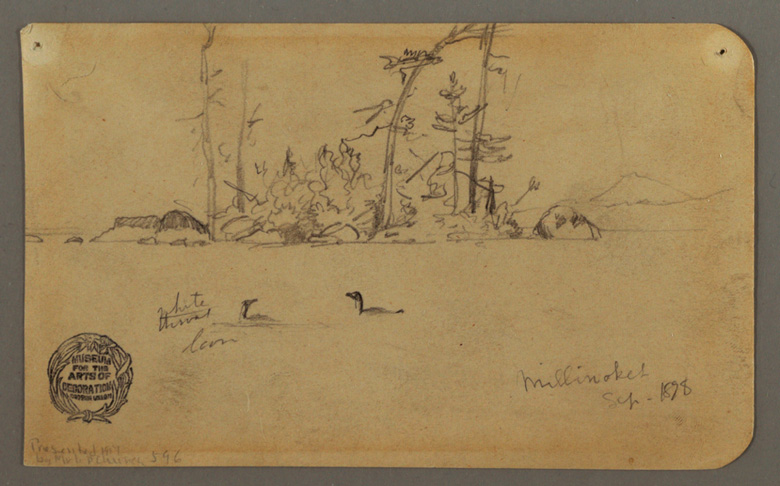

To shape an end, a parable from my own memory hoard. Obsessed, I will turn over and over in my mind all my precious encounters with these unknowable creatures, sorting them like so many jewels, polishing them, honing them through the idiosyncratic and solipsistic processes of mis- or re-remembering, taxonomy and poesis. I will sit motionless on my kayak for hours, just watching and listening, and I will write greedily in my journal, hoping to fix this ever-moving bird to the page. I will go on pilgrimage to marshy loon nurseries and watch the reptilian juveniles chatter and practice their vocalization. But my favorite memory, besides (indelible, fundamental!) the memory of my first time hearing the loon’s cry, is the strangest one. We are sea-kayaking in early April off the Blue Hill peninsula of Maine, crossing the terrifyingly deep and powerful Eggemoggin Reach—which is so placid and glassy on this brilliant morning that hardly a wave can be seen and it seems deceptively like every other stretch of ocean, not so muscular and fathoms-deep—and we are delighted by the heads of seals, popping up twenty feet off the boat. Suddenly ten or so harbor seals encircle our boat, their sleek muzzles huffing wetly with curiosity or indignation, and time stops in our otherworldly fairy ring. But then a strange noise breaks that uncanny silence, that frozen moment on the endless water—a kind of open-throated cry—unlike anything we have ever heard before. We look: and far off in the distance, near Crow Island, a raft of birds, maybe black and white, maybe grey—the mirage-like stillness of the water and the bright shine on the water surface makes it hard to tell—are they buffleheads? No: they are juvenile loons, a whole huge crowd of them! They are probably prepared to spend another year or two on the ocean water, mostly alone, but now for some reason they have convened in a parliament of fowls. Their tremolo calls are raw and untutored—nothing like the modulated refrains, choruses, and verses of their elders—they are still learning—and their voices are bright, open, reedy and rough.[31]

*

Viewed strictly as a water bird, as Nature intended, the Loon is a paragon of beauty. Alert, supple, vigorous, one knows himself to be in the presence of the master wild thing, when he comes upon a Loon, on guard in his native element.[32]

*

About the Author

Sarah is Assistant Professor of English and Honors at the University of Maine. She earned her undergraduate degrees in English and Spanish Literature at the University of Montana, and her Master’s and Doctoral degrees in Medieval Studies at Cornell University. Her scholarship contributes to discussions of the environment and literature, landscapes of power, and oral traditions. She seeks to situate the literature of the past within the context of concerns that are still relevant today, thus making medieval studies part of a broader interdisciplinary conversation. She is the author of The Ecology of The English Outlaw in Medieval Literature: From Fenland to Greenwood (Routledge 2016), and articles on Old Norse, Old English, and Middle English literature, as well as Honors pedagogy. Her current research includes an exploration of the late medieval English outlaw tradition as a seasonal virtual reality, a study of the malignant landscape in the Anglo-Norman poet Layamon’s Brut, and an examination of the depictions of the insular North-Atlantic land- and seascapes in Old Norse literature and later Scandinavian balladry.

Notes

[1] William Leon Dawson and John Hooper Bowles, The Birds of Washington. (Seattle: The Occidental Publishing Co., 1909), 896.

[2] See Kenner, Robert, Richard Pearce, Eric Schlosser, Melissa Robledo, William Pohlad, Jeff Skoll, Robin Schorr, et al. Food, Inc. (Los Angeles, CA: Magnolia Home Entertainment, 2009) for a vivid illustration of this problem of overbreeding and inhumane treatment.

[3] And loons can run on water—you’ll see them at the twilight hours in the morning and evening, sanding up, their wings flapping against the light, moving with great speed—almost like those motorboats. The dance on the water is so gorgeous to behold, apparently, it makes men of the cloth sound like pagans when they describe it: “A beautiful sight was that of three loons facing the rising sun, standing almost erect on the water, their great wings vigorously flapping, the sun shining full upon their pure white breasts. It seemed almost like an act of religious devotion in honor of old Phoebus.” The Reverend M.B. Thompson wrote this contribution to the ornithologist Arthur Cleveland Bent, who included it in his Life Histories of North American Diving birds, Order Pygopodes. (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1919), 56.

[4] For a creative rewriting and cooptation of the loon’s reputation, see Stacey Waite, “Becoming the Loon: Performance Pedagogy and Female Masculinity.” Writing on the Edge 19, no. 2 (2009): 53-68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43157302.

[5] The word immer is derived from Scandinavian forms, perhaps Norwegian or Faroese, which refer to the loon’s yearly appearance around Ember Days, a celebration before Christmas. See Ray Reedman, Lapwings, Loons and Lousy Jacks: The How and Why of Bird Names. (Exeter: Pelagic Publishing, 2016).

[6] Henry David Thoreau, “Brute Neighbors,” in Walden (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1910), 313-14.

[7] Oliver Austin, Water and Marsh Birds of the World. (New York: Golden Press, 1967). 9.

[8] Thoreau, “Brute Neighbors,” 313.

[9] The other possible etymon is, unsurprisingly, Old Norse. According to the OED, nothing is certain: “the early forms do not favour the current hypothesis of connection with early modern Dutch loen ‘homo stupidus’ (Plantijn and Kilian) which seems to be known only from dictionaries. The Old Norse lúenn, beaten, benumbed, weary, exhausted (past participial of lýja to beat, thrash) has been suggested as a possible etymon. The order of development of the senses is somewhat uncertain.” Curiouser and curiouser… From: “loon, n.1”. OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/110159?rskey=QcxG6o&result=1&isAdvanced=false (accessed February 08, 2017).

[10] Keith Stewart Thompson makes this point in his lovely essay, “The Common But Less Frequent Loon,” in The Common but Less Frequent Loon and Other Essays. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). 9-14, 10.

[11] My dad, a high school choir director, would affirm from his years of experience teaching large groups of high-schoolers that the full moon brings out the most extreme behavior in these strange creatures so directed by their biology—they’re temporarily insane.

[12] For a thoughtful study of the way the loons’ and wolves’ call activates deep ancestral memory, or as Sigurd F. Olsen would put it, “racial memory,” see Tom Klein’s Loon Magic, 3-4.

[13] Isidore of Seville, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), XX.xiii, 1-xiv.10, p. 404.

[14] Isidore, Etymologies, XII.i.31-i.44, p.249.

[15] For elucidation of the assimilation of these three words, see “loon, n.2”. OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/110160 (accessed February 08, 2017).

[16] According to the editors of the OED, “In Shetland repr. < Old Norse lóm-r; in modern literary use partly from Shetland dialect and partly < modern Swedish and Danish lom” “loom, n.2”. OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/110149 (accessed February 08, 2017). But I believe it is important to note that most Norse dictionaries identify lómr as the word for loon and, unlike the OED, connect it with the idea of lamentation. More on this later in the article.

[17] See also Walter Skeat’s gloss from his Concise Dictionary of the English Language (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1910), perhaps still the most honest partial elucidation of this riddle: “probably from the lame or awkward motion of diving birds on land; cf. Swed. dial. Loma, paralytic, E. Fries, lōmen, to move slowly” (301).

[18] This gloss is from Geir Zoëga’s Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 301.

[19] “lummox, n.”. OED Online. December 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/111135?redirectedFrom=lummox (accessed February 08, 2017).

[20] See Anatoly Liberman, “Old English gelōme, gelōma, Modern English loom, lame, and Their Kin.” In Old English Philology: Studies in Honour of R.D. Fulk. Eds. Leonard Neidorf, Rafael J. Pascual, Tom Shippey. (Martlesham: Boydell and Brewer, 2016) 190-199, 193, on the complicated history of this series of words.

[21] Another homophone that may be related: to loom, or, as Skeat glosses it, “to appear faintly at a distance” (348)—as succinct a description of the loon’s elusive appearance at a point far enough away from the human observer as to be indistinct.

[22] Zoëga, 309.

[23] Eric Partridge, ed, Origins. (New York: 1966), 304.

[24] Calvert Watkins, ed. “Lā-”. The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, 2nd ed., (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000) 34.

[25] See Joseph T. Shipley, The Origins of English Words. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1984).

[26] The Sagas of Icelanders: A Selection. Ed. Ornolfur Thorsson. (New York, Penguin Books, 2001).

“…og dreymir hann að fuglar kæmi í húsið er læmingjar heita, þeir eru meiri en rjúpkerar og létu illilega of höfðu volkast í roðru og blóði.”

“Mér bar hljóm í heimi,

hör-Bil, þás vit skilðumk,

skekkik dverga drykkju,

dreyra sals fyr eyru;

ok hjörraddar hlýddi

heggr rjúpkera tveggja,

koma mun dals á drengi

dögg, læmingja höggvi.”

[27] For a visual study of this behavior, see David Attenborough’s “The Problems of Parenthood” in Attenborough, David, Mike Salisbury, Fergus Beeley, Nigel Marven, Peter Bassett, Miles Barton, Joanna Sarsby, Ian Butcher, and Steven Faux.. The life of birds. (London: BBC Worldwide, 2002).

[28] Piper, W.H.; Walcott, C.; Mager, J.N. & Spilker, F. (2008b). “Fatal Battles in Common Loons: A Preliminary Analysis”. Animal Behaviour. 75 (3): 1109–1115.

[29] For more information, see www.loon.org/ingested-lead-tackle.php.

[30] See Seth Koenig, “Mercury causes ‘foggy-headed’ loons to fail as parents, possibly threatening their future.” Bangor Daily News, March 16, 2012; Kelly Slivka, “Mercury Sickens Adirondack Loons.” New York Times Blog Green, June 28, 2012. https://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/28/mercury-afflicts-much-loved-loons.

[31] For more on juvenile vocalizations on the ocean, or “antiphonal calling bouts,” see McIntyre, 87.

[32] Dawson and Bowles, 895. The author would like to thank the editors of Spire, Amelia Reinhardt, Heather Benner, Joseph Skerritt, and Justin Harlan-Haughey for their helpful comments on previous drafts of this piece.

Works Consulted

Attenborough, David, Mike Salisbury, Fergus Beeley, Nigel Marven, Peter Bassett, Miles Barton, Joanna Sarsby, Ian Butcher, and Steven Faux. The Life of Birds. (London: BBC Worldwide, 2002).

Austin, Oliver. Birds of the World. (New York: Golden Press, 1961).

—–Water and Marsh Birds of the World. (New York: Golden Press, 1967).

Bent, Arthur Cleveland. Life Histories of North American Diving birds, Order Pygopodes. (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1919).

Dawson, William Leon and John Hooper Bowles. The Birds of Washington. (Seattle: The Occidental Publishing Co., 1909).

Dunning, J. The Loon, Voice of the Wilderness. (Dublin, NH: Yankee Publishing, Inc., 1985).

Evers, David C., James D. Paruk, Judith W. McIntyre and Jack F. Barr. “Common Loon (Gavia immer),” The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology, (2010); Retrieved from the Birds of North America: https://birdsna.org/Species-Account/bna/species/comloo.

Imbert, Michel. ““Tawny Grammar”: Words in the Wild,” in Thoreauvian Modernities: Transatlantic Conversations on an American Icon. Edited by François Specq, Laura Dassow Walls and Michel Granger. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 265-273.

Isidore (Saint Isidore of Seville). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. S. Barney et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Kenner, Robert, Richard Pearce, Eric Schlosser, Melissa Robledo, William Pohlad, Jeff Skoll, Robin Schorr, et al. Food, Inc. (Los Angeles, CA: Magnolia Home Entertainment, 2009).

Klein, Tom. “Loonacy: What’s Black and White and Totally Enchanting?” Chicago Tribune. March 23, 1986.

—–Loon Magic. (Chanhassen: Northword Press, 1989)

Koenig, Seth. “Mercury causes ‘foggy-headed’ loons to fail as parents, possibly threatening their future.” Bangor Daily News, March 16, 2012.

Liberman, Anatoly. “Old English gelōme, gelōma, Modern English loom, lame, and Their Kin.” In Old English Philology: Studies in Honour of R.D. Fulk. Eds. Leonard Neidorf, Rafael J. Pascual, Tom Shippey. (Martlesham: Boydell and Brewer, 2016) 190-199.

Magnússon, Ásgeir Blöndal. Íslensk orðsifjabók. (Reykjavík: Orðabók Háskólans, 1989).

McAtee, W. L. “Folk Etymology in North American Bird Names.” American Speech 26, no. 2 (1951): 90-95.

McIntyre, J. W. The Common Loon: Spirit of Northern Lakes. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.)

Onions, C.T., et al., eds. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1966).

Partridge, Eric, ed, Origins. (New York: 1966).

Piper, W.H.; Walcott, C.; Mager, J.N. & Spilker, F. “Fatal Battles in Common Loons: A Preliminary Analysis.”.Animal Behaviour. 75 (3) ((2008b): 1109–1115.

Shipley, Joseph T. The Origins of English Words. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1984).

Skeat, Walter. A Concise Dictionary of the English Language. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1910).

Slivka, Kelly. “Mercury Sickens Adirondack Loons.” New York Times Blog, Green, June 28, 2012. https://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/28/mercury-afflicts-much-loved-loons.

Terres, J. K. The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American birds. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980).

Thompson, Keith Stewart. The Common but Less Frequent Loon and Other Essays. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1910).

Thorsson, Ornolfur, Ed. The Sagas of Icelanders: A Selection. (New York, Penguin Books, 2001).

Waite, Stacey. “Becoming the Loon: Performance Pedagogy and Female Masculinity.” Writing on the Edge 19, no. 2 (2009): 53-68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43157302.

Watkins, Calvert, ed.. The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, 2nd ed., (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000).

Zoëga, Geir T., A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004).

Public domain illustrations: https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18196177/