“A Trail is a Trail, and Land is Land”

How a Natural Gas Pipeline Reorganized Jurisdiction of Land Under Federal Administration

By Dominic Piacentini

Introduction

On July 5, 2020, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a 42-inch diameter, 604-mile-long natural gas pipeline was canceled by its leading partners, Dominion Energy, Duke Energy, Piedmont Natural Gas, and Southern Company Gas (Dominion Energy 2020). Among its many detractors, The Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change International (Goldtooth et al. 2021) celebrated this victory in indigenous and community opposition to carbon emissions and estimated that the cancelation of the pipeline prevented 67 million metric tons of annual CO2 pollution. Had the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) been completed, the pipeline would have disproportionately affected Lumbee and Haliwa-Saponi people in North Carolina. Lumbee scholar Ryan Emmanuel (2017, p. 260) says, “The nearly 30,000 Native Americans who live within 1.6 km of the proposed pipeline make up 13.2% of the impacted population in North Carolina, where only 1.2% of the population is Native American.” Land disputes that persist throughout the United States are frequently the result of ongoing colonization and practices of dispossession that are a feature of American governance. North of the Lumbee and Haliwa-Saponi tribes, the ACP was being routed through and constructed in ancestral lands of Monacan, Cherokee, and Shawnee people, much of which is now federal- or state-owned property. Broad coalitional opposition involving indigenous-led resistance, environmental activism, environmental justice, and eminent domain litigation was integral to halting the pipeline’s progress through these public lands.

Just a few weeks before the ACP was officially canceled, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the ACP was permitted to be constructed underneath the Appalachian Trail National Scenic Trail (Appalachian Trail). In this article, I discuss that Supreme Court case, United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al., which set new precedent for federal lands management and has applications to federally protected land in New England and beyond. This article relies on research I have done for my dissertation, involving policy and law review as well as ethnographic (qualitative, hands-on) fieldwork in Appalachia. I begin by introducing the ACP. I then describe the jurisdictional dispute between the U.S. Forest Service and the National Parks Service that is argued by the Supreme Court. I conclude by discussing the current state of the ACP and some of the implications United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation et al. has for protected land in Maine and New England.

Atlantic Coast Pipeline

In 2014, Atlantic Coast Pipeline, LLC, a joint venture between Dominion and its partners, announced plans to construct a 604-mile-long pipeline that would run through West Virginia and Virginia to North Carolina. The ACP would transport natural gas extracted from the Marcellus Shale — a deep, semi-permeable sedimentary rock that stretches underneath New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. Geologists have known for decades that natural gas exists in small pores of the Marcellus Shale, but traditional, vertical gas wells could not reach and break through the rock. The twinned technologies of horizontal drilling (the ability to shoot out multiple drills from a single wellhead) and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) provided oil & gas companies with the means to extract this fossil fuel. Though natural gas is seen by many to be a first step in an energy transition away from coal and oil as it emits less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, this perspective fails to account for the methane emissions that leak from natural gas wellheads. The Environmental Defense Fund (2022) estimates that these methane emissions have more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide, making it an incredibly potent greenhouse gas.

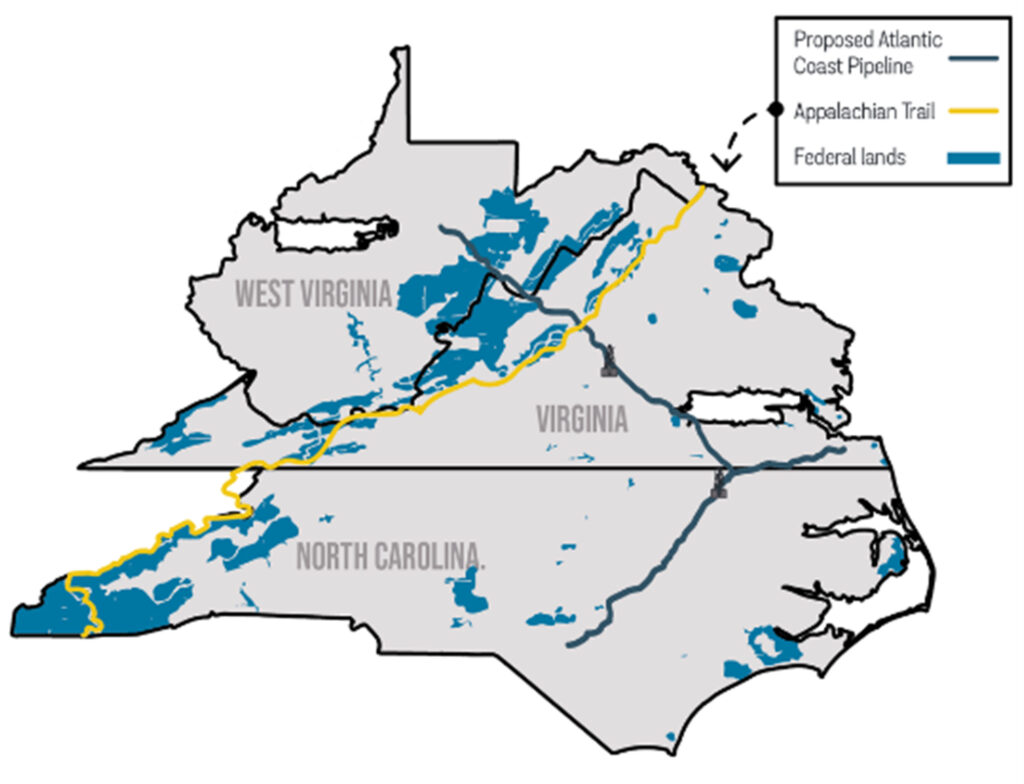

The ACP required a new energy corridor to be constructed through privately and publicly held land, including federal lands such as the Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia and the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests in Virginia. (Figure 1). One of the more interesting and contested crossings that the ACP would make is a section of right-of-way in Virginia that intersects with the Appalachian Trail in the George Washington National Forest. The Appalachian Trail is a 2,180-mile-long National Park Service unit that stretches from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Katahdin in Maine. The Appalachian Trail was federally designated in 1968 as part of the National Trails System Act, which declared that it would be administered by the Secretary of the Interior. Since that time, though, the Secretary of the Interior has delegated the administrative responsibility of the Appalachian Trail to the National Park Service (NPS), itself housed within the Department of the Interior.

Figure 1: Map of the proposed route for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and its intersections with federal lands and the Appalachian Trail. From Morshedi 2020.

The Appalachian Trail principally exists as a series of easement agreements with public and private landowners across the eastern United States, including the George Washington National Forest, managed by the U.S. Forest Service, within the Department of Agriculture. When the ACP proposed to cross the NPS administered Appalachian Trail within the George Washington National Forest, a jurisdictional dispute erupted over who had the authority to grant the ACP permission to bore beneath the scenic trail. Dominion Energy and its partners hedged their bets on the Forest Service overseeing the ACP’s easement under the Appalachian Trail. The Forest Service was set forth in law to administer federal land under a sustainable, multiple-use management concept intended to meet diverse needs beyond simply preservation or recreation. It was Richard E. McArdle, the eighth Chief of the Forest Service, who first said, “The national forests are lands of many uses – and many users,” which is why signage at national forests reads, “Land of Many Uses.” While the multiple-use management concept allows for more diverse and locally oriented land uses, it has attracted criticism throughout the years for privileging commercial users and extractive practices (Stegner 1988).

In 2017, the ACP did secure a special use permit from the Forest Service to install pipe 600 feet beneath the Appalachian Trail. Opponents of the pipeline, though, would argue that an easement across an NPS unit would also require NPS authority. The key argument of the opposition being that there are different requirements under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 that pertain exclusively to lands in the National Park System. The Mineral Leasing Act controls who has the authority to grant pipeline rights-of-way in federally managed lands, including the National Forests; however, the act’s authority excludes lands in the National Parks System. In order for a pipeline to be constructed in lands of the National Parks System, Congress would need to enact separate legislation independent of the Mineral Leasing Act. This argument was taken up by the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals when they vacated the ACP’s special use permit, halting any construction in the 16 miles of right-of-way through Forest Service land.

United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al.

When the special use permit to construct a pipeline in the George Washington National Forest was vacated, the ACP petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the Fourth Circuit’s decision. The United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al. was decided on June 15, 2020. Clarence Thomas wrote the opinion of the court, which Chief Justice John Roberts, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Ruth Bader Ginsberg joined. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the dissenting opinion, which Elena Kagan joined. The question at the heart of their arguments is whether or not all “units” of the NPS are “lands” in the National Park System. The Mineral Leasing Act enables any federal agency head to grant rights-of-way through their respective federal lands for pipeline purposes. The Act defines “Federal lands” as “‘all lands owned by the United States,’ except (as relevant) lands in the National Park System” (United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al., 2020, p. 2). The Appalachian Trail is undoubtedly an administrative unit of the National Park Service, a term which also includes national parks, national monuments, international historic sites, etc. The question became whether the Appalachian Trail is land within the National Park System.

The deciding opinion argued that although the Appalachian Trail is a unit of the NPS, it is not land within the National Parks System and therefore not excluded from the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 which permits the Forest Service to grant a pipeline right-of-way through the George Washington National Forest. This argument relies on the fact that like the ACP, the Appalachian Trail is itself an easement on Forest Service property. Justice Thomas wrote in the deciding opinion, “A right-of-way is a type of easement. And easements grant only nonpossessory rights of use limited to the purposes specified in the easement agreement […] A right-of-way between two agencies grants only an easement across the land, not jurisdiction over the land itself” (ibid, p. 2). That is, because the Appalachian Trail exists only as a right-of-way through the George Washington National Forest, the NPS does not have authority or jurisdiction of the land to which the easement grants right-of-way. For Justice Thomas, the case is a semantic one saying, “Sometimes a complicated regulatory scheme may cause us to miss the forest for the trees, but at bottom, these cases boil down to a simple proposition: A trail is a trail, and land is land” (ibid, p. 10). Can it really be as simple as that? The regulatory scheme that is undercut here concerns the mechanisms by which the NPS could functionally administer a unit of the National Parks System without having any jurisdiction over the land itself. If the NPS does not have the authority to manage the land on which the Appalachian Trail runs, how can it actually administer the unit for the public?

Justice Sotomayor writing the dissenting opinion draws on The Organic Act, which established the NPS and says that a National Parks Systems “unit” is “land” or “water” (United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al, 2020, dissenting opinion, p. 2). Sotomayor meets Thomas’s tone of argument when she says, “Unless the Court means to imply that the Appalachian Trail is water, the Trail must be land in the Park System,” and therefore the ACP cannot rely on the Mineral Leasing Act (ibid, p. 11). The dissenting opinion argues that federal law does not distinguish land from trail any more than it distinguishes land from the monuments, historic buildings, parkways, and recreational areas that make up the National Parks System and of which the NPS has jurisdiction. They argue that even if the method of acquisition is an “easement” or “right-of-way” through the National Forest, the NPS is nevertheless the lead federal administrator for the entire Appalachian Trail because the easement is to the trail and the land on which the trail sits is an implied prerequisite necessary for the maintenance of the trail. That is, protection and administration of the trail is not possible without protecting and administering the land.

“… protection and administration of the trail is not possible without protecting and administering the land”

Ultimately, the court decided that “trail” does not equal “land” and that the NPS easement is therefore irrelevant to the case at hand. Both the ACP and the Appalachian Trail are two easements that happen to intersect in the George Washington National Forest, but both remain under the ultimate jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service. By overruling the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals revocation of the special use permit in question, the ACP was permitted to burrow beneath the Appalachian Trail, though there were several other key permits that had been vacated or not yet authorized preventing the ACP from further construction at the time of the decision.

Conclusion

Ironically, 20 days after the Supreme Court issued this decision, Dominion Energy and its partners announced that they would be canceling the ACP, saying in a press release, “Despite last month’s overwhelming 7-2 victory at the United States Supreme Court, which vindicated the project and decisions made by permitting agencies, recent developments have created an unacceptable layer of uncertainty and anticipated delays for the ACP” (Dominion Energy 2020). The ACP was already years behind schedule and billions of dollars over their original estimated cost. Despite clearing the hurdle that the Appalachian Trail represented, there were a dozen more hurdles yet to overcome in an increasingly unstable market affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing political opposition, and natural gas prices.

Although the ACP was canceled, United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al. remains a victory for fossil fuel industries, pipelines, and energy corridors as it sets a formidable legal precedent giving little-to-no jurisdiction to the NPS to prevent construction in, on, under, or over the Appalachian Trail or other more nebulous “units” of the National Park System. The Appalachian Trail is a unique unit of the NPS that connects the entire eastern United States, from Georgia to Virginia to New York and Maine. The decision made by the Supreme Court sets precedent for future pipelines to be given right-of-way across the Appalachian Trail within the White Mountain National Forest on the New Hampshire side of the border and puts into question the extent of legal jurisdiction the NPS has over non-park units including sites in Maine, such as the Appalachian Trail, the St. Croix International Historic Site, Roosevelt Campobello Island International Park, and the Katahdin Woods & Waters National Monument.

U.S. governance of land and waters has been a historic morass of jurisdictional disputes that most often give way to the expansion of settler colonialism and the proliferation of the fossil fuel industry. United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al. asks us to question how many uses the “land of many uses” can sustain and which uses we should curtail or cultivate. The multiple-use management concept of the U.S. Forest Service provides local resource users and recreationists opportunities unavailable to them in the more restrictive National Park System, such as the collection of wild plants for food or medicine. However, careful consideration of diverse needs must be made as more powerful users, like the ACP, advocate for their own use over the uses of others. Those opposed to the ACP saw the restrictions of the National Parks System as an opportunity to protect their own uses of the National Forest, including an undisturbed Appalachian Trail and clean air and water. Although the ACP was canceled, this case nevertheless provided the U.S. Forest Service with new precedent to maintain and expand the commercial and extractive use of federally managed land.

References

Dominion Energy. 2020, July 5. Dominion Energy and Duke Energy cancel the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Accessed February 5, 2022. Retrieved from https://news.dominionenergy.com/2020-07-05-Dominion-Energy-and-Duke-Energy-Cancel-the-Atlantic-Coast-Pipeline.

Emmanuel, R. E. 2017. Flawed environmental justice analyses. Science, 357 (6348), 260.

Environmental Defense Fund. 2022. Methane: A crucial opportunity in the climate fight. Accessed March 7, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.edf.org/climate/methane-crucial-opportunity-climate-fight.

Goldtooth, D., Salamando, A., Gracey K., Goldtooth, T., and Rees, C. 2021. Indigenous resistance against carbon. Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change International. Washington, DC. Accessed March 7, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ienearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Indigenous-Resistance-Against-Carbon-2021.pdf.

Morshedi, M. 2020, February 20. Can the Appalachian Trail block a major natural gas pipeline project? Accessed December 29, 2021. Retrieved from https://subscriptlaw.com/atlantic-coast-pipeline-v-cowpasture/.

Stegner, W. 1988, Nov. 20. Land of many uses and abuses. Los Angeles Times. Accessed March 8, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-11-20-op-370-story.html#:~:text=That%20is%20why%2C%20in%20national,and%20wildlife%20and%20fish%20habitat..

United States Forest Service et al. v. Cowpasture River Preservation Association et al. No. 18–1584 (2020). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-1584_igdj.pdf.