For UMaine emerald ash borer researchers, preparing for the inevitable is an act of hope

Story by Sam Schipani

Emerald ash borer — or “EAB,” as it is known by those who study it — is an invasive insect that will decimate ash tree populations in Maine, as it has done in so many other places across the country. It’s not a matter of if, but when.

At the University of Maine, that inevitability is not met with despair, but hope, thanks to years of interdisciplinary research supported by the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions. Together, the Wabanaki Nations, UMaine’s dedicated researchers and the collaborating state entities responding to EAB have been able to develop innovative management and adaptation strategies that integrate Indigenous knowledge as a guiding influence to deal with the invasive pest — and, hopefully, preserve ash trees for generations to come.

The legacy of EAB research

EAB devastates ash trees from the inside out, burrowing into the inner bark and cutting off the circulation of nutrients and water until the trees wither away. There is no saving a tree once EAB has really dug in, and, as of right now, there’s no way to stop the spread of the invasive species in the United States.

The bright green bug feasts on all types of ash trees, from white ash that is prized for quality furniture to hardy green ash like the trees that shade the UMaine Mall. However, EAB favors brown ash, also known as black ash, which is the best material for traditional Indigenous basket making.

In 2009, UMaine researchers, including those affiliated with the Mitchell Center, started looking at the potential impact of EAB on Maine’s ash trees, and how to address it in a way that integrates Indigenous perspectives and interests. Even though there was no EAB detected in Maine at that point, researchers, foresters, and Wabanaki basketmakers alike were anxious to get ahead of the issue. They heard about the EAB devastation in places like Michigan, where the pest wiped out nearly all ash trees in the state.

John Daigle, UMaine professor of forest recreation management, and Darren Ranco, professor of anthropology and chair of Native American Programs, have been involved with the project since its inception. They are both Mitchell Center faculty and citizens of the Penobscot Nation.

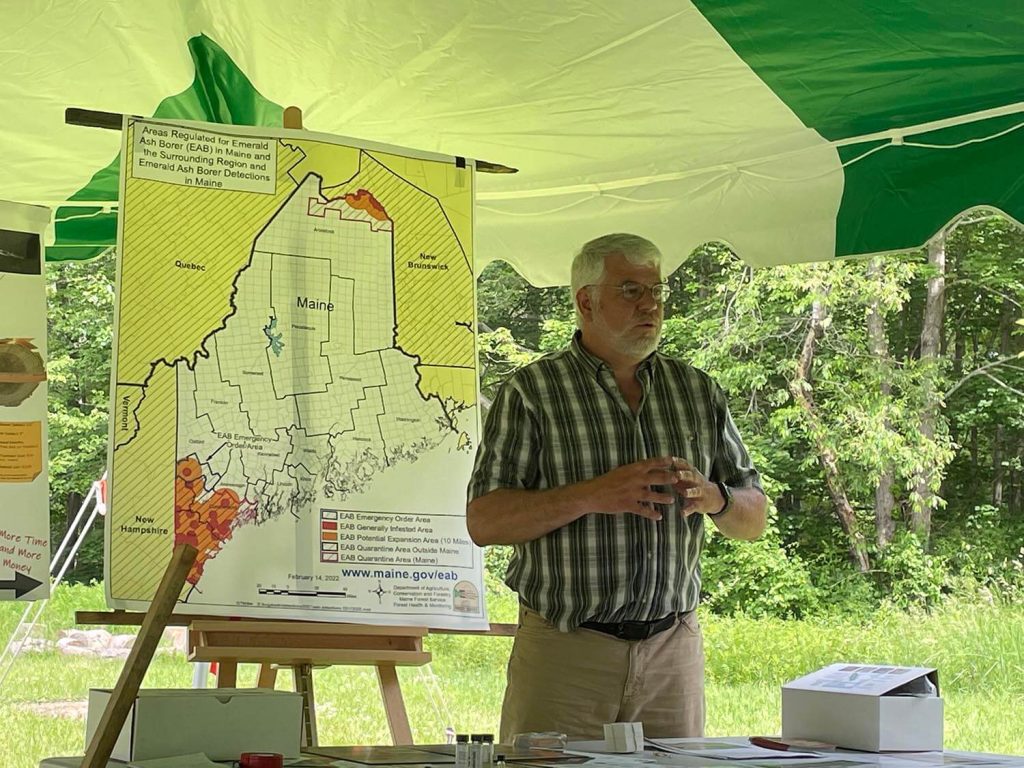

A lot has changed since 2009. EAB was first detected in Maine in 2018, but the efforts of UMaine researchers paid off. Thanks to the establishment of the EAB-Brown Ash Task Force in collaboration with Maine’s Wabanaki Nations and the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry (DACF), policies like quarantine zones and firewood bans have helped slow the spread of EAB across the state.

“The majority of our ash is still healthy in the state of Maine. Being proactive with policy, outreach and other things has made a difference,” Daigle said.

Ranco said that success also comes from EAB discussions centering Wabanaki voices and interests from the beginning.

“This also meant that UMaine, and the Mitchell Center more specifically, could serve as a key convener of both Tribal and statewide scientific and policy response, and could contribute in productive ways,” Ranco said.

But now that EAB is here, the work has entered a new era: adaptation. UMaine’s Ash Protection Collaboration Across Wabanakik (APCAW) network is leading the way.

Preparing the forest for EAB

Tyler Everett, a Ph.D. candidate at UMaine’s School of Forest Resources, is using forest management to prepare the next generation of ash trees for the inevitable wave of EAB.

Everett, who is Mi’kmaq, interned for the Passamaquoddy Forest Department as an undergraduate at UMaine, and worked there after graduation. The department encouraged him to pursue further education in the field. After enrolling in the Master of Forestry program at UMaine, he attended a Brown Ash Task Force meeting. After witnessing the integration of Indigenous knowledge into forest management firsthand, he wanted to be a part of it.

During his master’s program, Everett inventoried ash trees to find good quality brown ash sites. For his Ph.D., he focuses on managing forests in a way that will make them more resilient to EAB outbreaks, removing weaker “low vigor” trees that would attract and build up EAB while also creating gaps in the canopy.

“Brown ash is shade intolerant; by creating these gaps, we’re promoting natural regeneration,” Everett said. “Hopefully, that natural regeneration would be that cohort that survives the initial wave of emerald ash borer and gives us time to manage that site.”

Daigle notes that Everett’s silvicultural research pairs well with other management methods, such as selective insecticides and the use of natural EAB predators including nonnative and stingless parasitic wasps, a biocontrol method that the Maine Forest Service is testing.

Everett also hosts discussions with Wabanaki communities about EAB management; he has held meetings with three of the five tribes in Maine and hopes to meet with the others this summer.

Everett says one of the greatest experiences for him has been getting to learn more about basket making over the course of his research. He even made a miniature pack basket that the flower girl used in his wedding, with sweetgrass woven into the rim.

“I have been finding out a lot about my culture through my research,” Everett said. “Basketmakers say that there’s no replacement for brown ash when it comes to basketry, and until you get a chance to hold it in your hands and work with it, you can’t appreciate how true that is.”

Collecting ash seeds for the next generation

In addition to preparing the next generation of ash trees for an EAB invasion, researchers at UMaine are collecting ash seeds to preserve the genetic diversity of the trees. For example, Daigle said some trees show more resistance to EAB, and scientists may be able to build a more resilient tree through grafting.

Over the years of her Ph.D. program at UMaine, Emily Francis has led the development of a seed collection manual for ash. The guide was created in partnership with Les Benedict of the Akwesasne St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in present day New York, and speaks to the strength of UMaine’s EAB partnerships.

“That seed manual would not have happened without him,” Francis says. “There hasn’t been the care and time within the science community to dedicate to brown ash the way there is with other species. It was very frustrating for me to find information, except for Les Benedict’s article on ash. I couldn’t imagine trying to be a private landowner who wants to help or somebody who wants to collect seed.”

Francis just hopes that the seed collecting guide has arrived in time; ash trees only produce seed every 5 to 8 years, and the last banner year for seeds was as recent as 2022.

But Everett is confident that these initiatives are, in fact, right on time.

“This year, early forecasting of brown ash seed development has been positive, giving us all hope that collections of brown ash seed this fall will be numerous,” he said. Community members who want to get involved should follow the APCAW website for seed collection events.

Plus, they have the next generation on their side. The Wabanaki Youth in Science (WaYS) program has incorporated ash seed collection kits into their curriculum, and the Gulf of Maine Research Institute will bring seed kits into the classroom. The Wild Seed Project is also partnering with APCAW to bolster their capacity to collect ash seeds.

Francis also spent her Ph.D. studying what has made Maine’s EAB network successful, and how states can apply the model to deal with other invasive species.

“I was really interested in learning about how a group can come together so far in advance of a threat and stick with it once the threat is present,” Francis said.

Francis also worked with Everrett to survey landowners, foresters and loggers about their understanding of EAB, what their forest management responses might be, whether they would be interested in allowing for cultural access by Wabanaki basket makers, and what the barriers to allowing that access might be. Between their two surveys, there were over 800 respondents and plan to publish the results.

“On the whole, people want their forests to be healthy,” Francis said. “They want to take part in adaptive management strategies, but they want to know what the costs are. They want to see that their neighbors and peers have had success with this and they can see success as well. It’s not a perfect world, there are no guarantees, but the fact that people are willing to take part is exciting.”

Communicating EAB strategies

Communication ties all the interdisciplinary research together into actual change; that’s where master’s student Ella McDonald comes in.

McDonald joined APCAW in fall 2022 as a graduate student in the Ecology and Environmental Sciences Program. Through their masters program, McDonald has conducted education and outreach efforts across various stakeholder groups. During 2023, McDonald organized 10 events both online and in person around different topics of protecting ash trees in Maine, reaching over 900 people.

“I think often environmental issues feel daunting because it’s often focused on individual choices. Something exciting about outreach is that it’s an opportunity to make this work collective, and connect people who also care deeply about these issues and want to make a difference,” McDonald said.

McDonald surveyed event participants to see what the impact of these events has been, like whether participants are collecting seeds or caring for their ash stands, to figure out how to better support and encourage citizen science efforts.

In addition to the events, McDonald created a website and a newsletter to provide the public with information about ash inventory and seed collection, and was featured prominently, along with Francis, in a Maine Public segment about collecting ash seeds in October 2023.

“That gathering was great to not only shed light on the importance of collecting ash seed, but how to do it. I hope that people can see that it can be really fun to go out into the forest with a group of people and collect seed,” McDonald said.

In the coming years, Daigle says that maintaining communication with landowners, Tribal Nations and the general public will be critical to ensure that protecting ash in the face of EAB is not seen as a “lost cause.”

“I think it’s important to try to sustain that hope,” he says.

A new hope for EAB

The grip of EAB is starting to feel heavy, according to Ranco, and Francis says there is “still a psychological hump that everyone in Maine is going to have to get over when they see the damage from the ash across the state.”

“There’s going to be loss,” Francis says. “Just because there is loss doesn’t mean there isn’t a light at the end of the tunnel. We just need to remember it’s a very long process. Trees are not agricultural crops. This is a decades-long slog that we’re going to have to go through to see ash secure on the landscape.”

Everett is emboldened by the strides in research, and the interdisciplinary way the EAB issue has been approached.

“Nobody is an expert on all things; it takes everyone collectively in action,” Everett said. “Through that, and through research, I’ve learned some things that give me hope.”

Daigle and Ranco also said that the Mitchell Center’s interdisciplinary approach to the EAB issue has been key to the successes that the state has experienced so far when it comes to preparing for and controlling the spread of EAB.

“The (Mitchell Center’s) ethos is without its equal anywhere I have worked,” Ranco said. “The values cut to the core of what makes UMaine great and special, and reflects a deep commitment to Wabanaki homelands, places and sovereignty.”

The EAB work has also created a model for other projects addressing invasive species challenges by focusing on relationship building, especially for long-term projects. Daigle said that keeping up momentum, interest and satisfaction with a long-term project that does not show immediate results is challenging, but the EAB team at UMaine has shown that it is possible.

“You can’t do research and just leave. You have to maintain those relationships. You have got to stay connected,” Daigle said.

Contact: Ruth Hallsworth, hallsworth@maine.edu