Composting at the University of Maine

Off Rangeley Road, behind the Printing and Mailing Services, there is a hidden gem on the University of Maine’s campus. It’s forty fe et long, one of a kind, nine years old, and costs $140,000. It is the University of Maine’s composting system. This composter takes in 4500 to 5000 pounds of food from the dining halls every week and turns it into organic dirt that is used on campus, making this a full circle process. Green Mountain Technologies created this compost system for individual farm use, so there have been several improvements throughout the past few years to boost the composter to be ready for industrial use.

et long, one of a kind, nine years old, and costs $140,000. It is the University of Maine’s composting system. This composter takes in 4500 to 5000 pounds of food from the dining halls every week and turns it into organic dirt that is used on campus, making this a full circle process. Green Mountain Technologies created this compost system for individual farm use, so there have been several improvements throughout the past few years to boost the composter to be ready for industrial use.

Everything our composter uses comes from the University and everything our composter makes goes right back to the University. We use a mixture of 1 part nitrogen to 2 parts carbon, our nitrogen comes from our pre-consumer waste from the dining halls, our carbon comes from Witter Farms, specifically their horse manure. These two pieces get mixed together and put into the large composter. Inside the composter, there is a large auger that moves through the compost and mixes it. The mixing process creates a reaction between the carbon and nitrogen that produces heat as high as 170 degrees Fahrenheit. The composter can break down most anything, from vegetables to meats. This process takes 18 to 21 days, and when the compost comes out the other side, it is unrecognizable. After the three weeks in the composter, the dirt needs to set and cure for six to eight weeks and then is completely ready for use.

Broken parts don’t stop our composting system here, we still have backup systems to continue long-term composting, such as bin composting and creating the same mixture in other storage systems. In the summer, there is a lack of compost materials, so the system usually switches to bin composting instead. The academic year is the focus of the composting program at the University of Maine, including tours of the unit, the Maine Compost School, and several classes that visit the composting unit on a regular basis.

Many people on campus have suggested using post-consumer compost as well as pre-consumer compost. At the moment, the Resource Recovery program only uses pre-consumer compost because of the control of pre-consumer materials. Post-consumer materials usually contain a lot of plastic, which will not break down in the composting unit. In addition, the composter is already at capacity and taking in more than enough to close the circle at the University of Maine, therefore, there is no need for more material from post-consumers.

20 years ago, the University of Maine was producing over 3 million pounds of waste a year, and now the University of Maine is producing less than 2 million pounds of waste. If you’re looking for a way to help the University’s low waste efforts, there are lots of options to live a low waste life. If you’re not able to compost in your apartment or dorm, look for local businesses that will pick up organic waste in the Orono area. These types of groups will collect your waste and use it for their own compost, so at least your food waste isn’t going into landfills. You can create your own compost bins and use the same nitrogen to carbon ratio that we use on campus. Another idea that Resource Recovery mentioned is returning plastic bottles. There are hundreds of plastic bottles that could be going to redemption centers in our recycling bins to get the consumer a little bit of money back instead of going to the recycling center, keep your bottles out of the recycling and take them to a redemption center instead! These are all ways that the experts at the University of Maine’s Resource Recovery suggest starting your own sustainable habits.

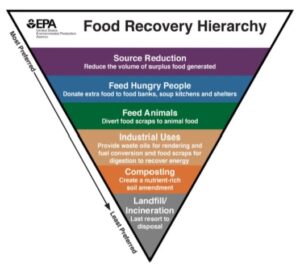

Overall, our composting unit is a shining example of sustainability at the University of Maine, but composting is only a small part of the Food Recovery Hierarchy. The Food Recovery Hierarchy is a visualization of where our food should be going to make sure that what food we have is used in the best way possible. The most important part of the Food Recovery Hierarchy is source reduction, so this holiday season, make sure to only put food on your plate that you’ll eat.

Overall, our composting unit is a shining example of sustainability at the University of Maine, but composting is only a small part of the Food Recovery Hierarchy. The Food Recovery Hierarchy is a visualization of where our food should be going to make sure that what food we have is used in the best way possible. The most important part of the Food Recovery Hierarchy is source reduction, so this holiday season, make sure to only put food on your plate that you’ll eat.

Special thanks to Mark Hutchingson, Scott Foster, and Jim Mitchell for their time to answer questions and their passion for the composting system here at the University of Maine.

To read more about the Food Recovery Hierarchy: US EPA, OLEM. Food Recovery Hierarchy. 12 Aug. 2015, https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/food-recovery-hierarchy.