Navigating the Ocean Uncommons

Emma Polhemus worked as a summer research intern at the University of Maine Darling Marine Center in 2023. Mentored by Drs. Jessica Reilly-Moman and Heather Leslie, Emma focused on participatory social science to support ocean renewable energy development. She is about to begin her junior year at the University of Vermont.

I wrote a picture book about renewable energy for a 5th grade project. The pages were filled with drawings of solar panels and plants and wildlife: a ten-year-old’s vision of environmental utopia. I remember carefully tracing wind turbines from a projector onto the page, complete with sunny skies and rolling green hills.

Eight years later, I declared my university major in environmental science. My view of our environmental future would change from happily spinning turbines to charts of carbon dioxide concentrations and global temperatures and sea levels, all rapidly rising toward total environmental crisis. So when I first started my research internship at the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, I knew that we needed renewable energy to meet that crisis, and offshore wind energy could be an integral part of transforming our current energy system. I was excited to join a social science research project on the topic, which felt like a tangible way to ease public concerns and facilitate that transformation.

However, after learning more about the project, it seemed to me that the participatory social science methods we would be using, including interviews, might highlight local resistance to ocean renewable energy without moving toward a solution. If the research showed that many people are opposed to offshore wind, would that mean we should give up on a picture book clean energy future?

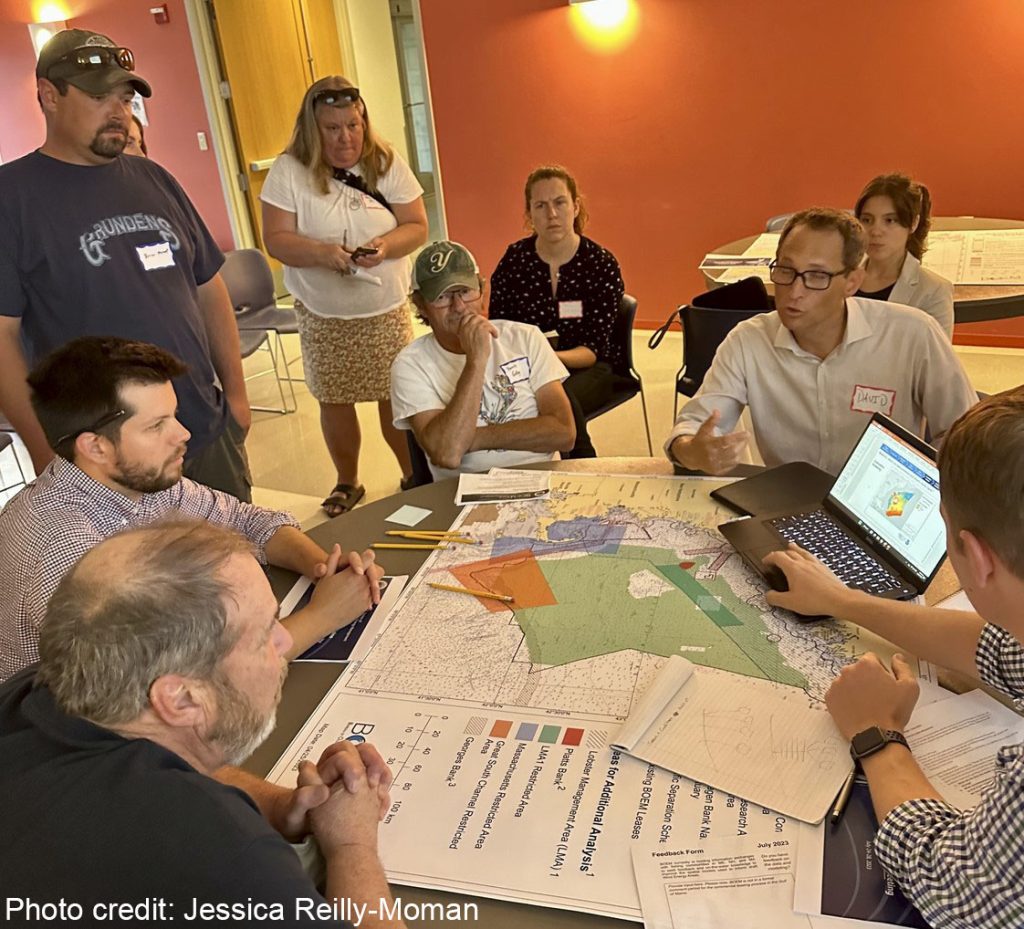

I imagine offshore wind farms as something like the picture-book drawings I made: turbines standing tall, the sea sparkling beneath them. I look at images of such farms and feel relieved that we’re making climate-smart energy decisions. However, when fishermen attending a public forum convened by the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management looked at a map of potential developments, they saw threats not only to the fisheries industry and their livelihoods, but their generational legacy and a way of life they hoped to pass on to their grandchildren.

For many coastal residents and ocean users, the ocean represents a livelihood, a tradition, and a sense of place and belonging. Offshore wind developments could threaten these connections for some people. Such developments could lead to loss of commercial fishing grounds, industrialization of seascapes, and harm to seabirds and other marine life. Beyond these impacts, stakeholders may feel that planning processes do not provide them with a meaningful role in project decisions.

Learning more about these challenges was an awakening for me. Having grown up in the midst of the climate crisis, working toward clean energy development feels personal and urgent. I hadn’t envisioned that transformation forcing the consequences onto an important heritage industry and the people—fishermen and others—who love their work and lives on the sea.

I am not, of course, the first person to take an interest in making ocean renewable energy development more suited to the communities it will impact. Current approaches to mitigating conflicts include choosing development sites to avoid important animal habitats, creating methods to use turbine bases for shellfish or seaweed aquaculture, and integrating boat transit lanes between turbines. In each case, the first step was making a commitment to recognize and respect the multiple uses of ocean spaces. This approach to shared resource management is often referred to as ecosystem-based management (McLeod and Leslie 2009).

Our oceans are a type of commons, accessible to many and managed collectively. Building on this idea, the concept of an “uncommons” considers the different worldviews that create and are created from different uses of a natural resource, like the oceans or the fish that live in them. In A World of Many Worlds, Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser (2018) describe an uncommons as “the negotiated coming together of heterogeneous worlds (and their practices) as they strive for what makes each of them be what they are, which is also not without others” (p. 4). In offshore wind development, the ocean is the centerpoint, acting as both a potential clean energy resource and as a traditional shared livelihood. For those who work at sea, offshore waters can gain a unique significance as an identity- and community-forming place; in other words, these deep waters “make them be what they are” (p. 4). Acknowledging these diverse ways that people relate to the ocean may help facilitate more productive conversations about how these spaces might change with offshore wind development.

After my summer research experience at UMaine, my perspective on offshore wind and other renewable energy technologies has changed. I’m not universally supportive of such development, as I was before, but I still believe that ocean renewable energy can enable us to thrive in the face of the climate crisis when community needs are expressed and met as part of the development process. We need to figure out how communities and developers can navigate paths through their uncommons, finding uses of the shared commons that support renewable energy goals and community needs.

Everybody could get a marker in this new picture book. We can make the next pages together.

To learn more about ocean renewable energy development, see the poster that Emma presented at the DMC summer research symposium in August 2023 and these resources:

de la Cadena, M., & Blaser, M. (Eds.). (2018). A World of Many Worlds. Duke University Press.

Haggett, C., ten Brink, T., Russell, A., Roach, M., Firestone, J., Dalton, T., & Mccay, B. J. (2020). Offshore wind projects and fisheries. Oceanography, 33(4), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/26965748

Hall, D. M., & Lazarus, E. D. (2015). Deep waters: Lessons from community meetings about offshore wind resource development in the U.S. Marine Policy, 57, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MARPOL.2015.03.004

McLeod, K. L., & Leslie, H. M. (Eds.). (2009). Ecosystem-based management for the oceans. Island Press. Read it online.

Emma’s research experience was supported by

- A grant to Drs. Leslie and Reilly-Moman (R/22-24-NESGR-Leslie) funded by a partnership among the Northeast Sea Grant Consortium, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Energy Technologies Office and Water Power Technologies Office, and NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science;

- Student Research funds from friends of the UMaine Darling Marine Center; and

- A faculty grant to Prof. Heather Leslie from the Henry David Thoreau Foundation.

To learn more about undergraduate research opportunities at the UMaine Darling Marine Center, please contact Prof. Leslie at heather.leslie(at)maine.edu or visit the DMC website at https://dmc.umaine.edu/. If you would like to support undergraduate research at the DMC, we would welcome your support; details on giving are at https://dmc.umaine.edu/giving/.