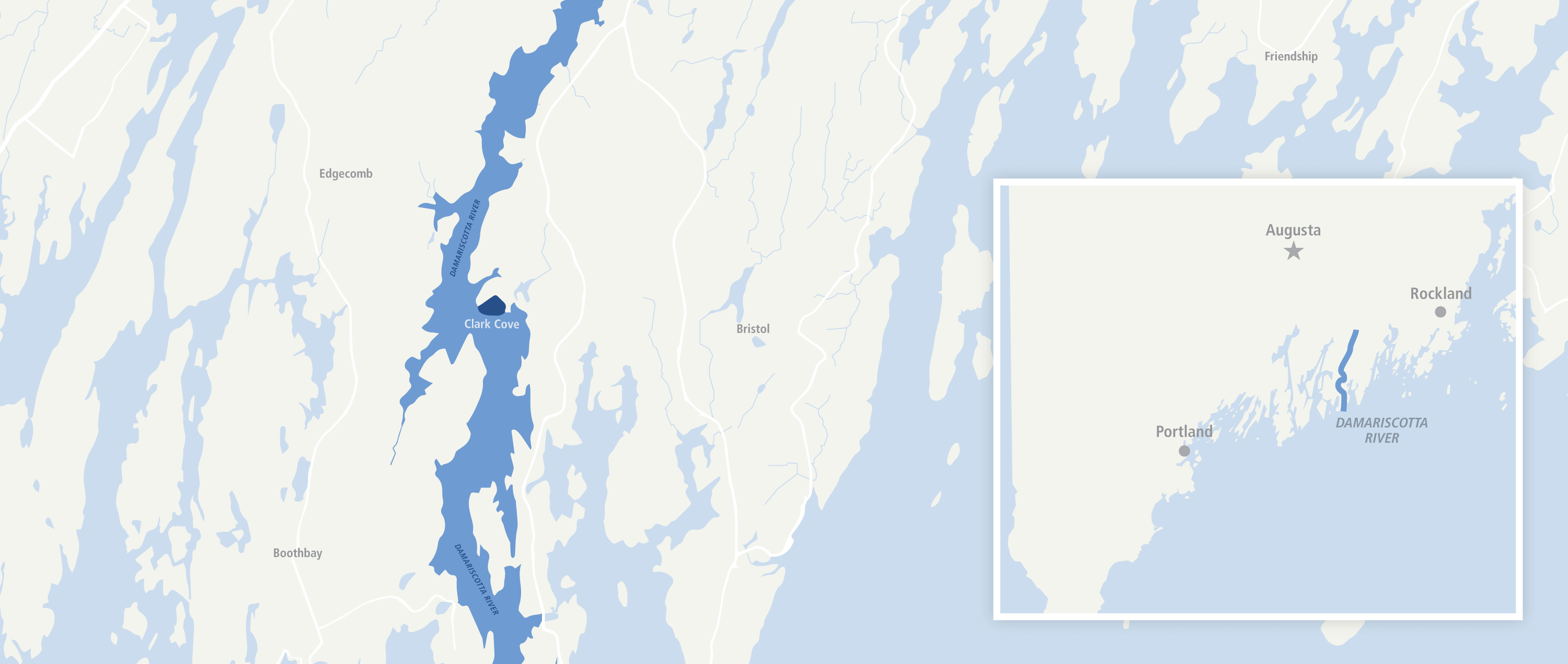

Maine’s Clark Cove has long been a farming community.

The 40-acre inlet on the Damariscotta River estuary, six miles up the state’s rocky coast, is home to numerous farms, and a diversity of crops.

But what’s most notable is the way the crops are grown.

Underwater.

With clean, cold and nutrient-rich waters, the estuary — where freshwater and saltwater ecosystems meet — is an ideal environment for growing marine animals and plants, including oysters, mussels, clams and sea vegetables.

Aquaculture in the ocean, commonly referred to as sea farming, is one of the major economic engines for the Damariscotta River. Since the establishment of Maine’s first sea farm in Clark Cove in 1975, the state’s aquaculture industry has grown to 107 companies totaling approximately 113 lease sites, employing approximately 600 people.

In 2014, the overall economic impact of Maine aquaculture was $137.6 million, according to the Aquaculture Research Institute (ARI) at the University of Maine.

For more than four decades, UMaine has conducted research and provided educational outreach related to the farming of aquatic organisms, such as finfish, shellfish or sea vegetables. On campus and at UMaine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research (CCAR) in Franklin, Maine; statewide through Maine Sea Grant College Program, headquartered on campus; and at UMaine’s Darling Marine Center in Walpole, Maine, research in oceanography, production, animal husbandry, genetics and diseases informs the development of Maine’s aquaculture industry and trains its workers.

In 2014, that support took a giant step forward with the creation of Maine’s Sustainable Ecological Aquaculture Network (SEANET), directed by UMaine Vice President for Research Carol Kim. Paul Anderson, who also leads Maine Sea Grant and ARI, is research network director.

Maine EPSCoR and ARI at UMaine oversee SEANET, which is funded by a five-year, $20 million grant from the National Science Foundation. With its R&D focus, the project includes UMaine and 10 other institutions, as well as a cohort of aquaculture farmers statewide.

Researchers are using Maine’s 3,500-mile coastline as a living laboratory to gather environmental data using a buoy-based sensor system to model aquaculture’s carrying capacity in the state’s dynamic coastal systems.

The network of six buoys — sited in areas with a variety of physical features in the Gulf of Maine — measure oceanographic and biogeochemical conditions to better understand what drives the productivity of Maine’s estuaries. The technology records air and water temperature, nutrient availability, turbidity, pH, dissolved oxygen, wind strength and direction, wave height, salinity, concentrations of phytoplankton, and the speed and direction of the current at several depths.

Any changes in these variables impact the marine environment, which subsequently impacts the businesses that rely on these waters to grow their products.

“When an aquaculturist or grower starts, it may take two years to get a lease. Then it might take another two years to get their product to market. So there are a lot of risks along the way,” says Damian Brady, an assistant professor at the Darling Marine Center. “We are trying to understand and minimize those risks to help farmers and growers succeed in their business.”

Brady oversees Maine Sea Grant’s research portfolio and is a lead researcher for SEANET. His work focuses on how changes in marine environments affect the ecophysiology of marine organisms, and looks at how climate change is impacting the aquaculture industry now and into the future.

“What we see here at the Darling Marine Center as our mission is to help the aquaculture industry with the problems that may be impediments to the growth of that industry — from disease resistance and enhancing production, to being the R&D arm for this industry,” Brady says.

Matthew Gray, postdoctoral research associate at the Darling Marine Center, was hired to maintain and deploy the buoys, and works with Brady to study how organisms respond to their environment. He is particularly interested in the physiological effects ocean acidification can have on marine invertebrates, such as mussels, clams and oysters.

“The farmers are depending on the environment to provide the food for their crops,” Gray says. “It’s important to understand where that food comes from and the factors that influence its availability, as well as the numerous environmental conditions that help these species grow, like temperature, dissolved oxygen, the acidity of the water — all these things are really important for a grower to know. It makes a real difference to their bottom line.”

“When we run these models, and after all the work is done, we hope that the access to aquaculture is greater, as well as the reliability when it comes to site selection,” he says.

Seafood production is affected by environmental quality, and as these conditions change due to climate change or other factors, it’s important to understand how the species will respond. That’s where the buoy data can help.

For shellfish farmers, the success of their business is dependent on the health of the oceans.

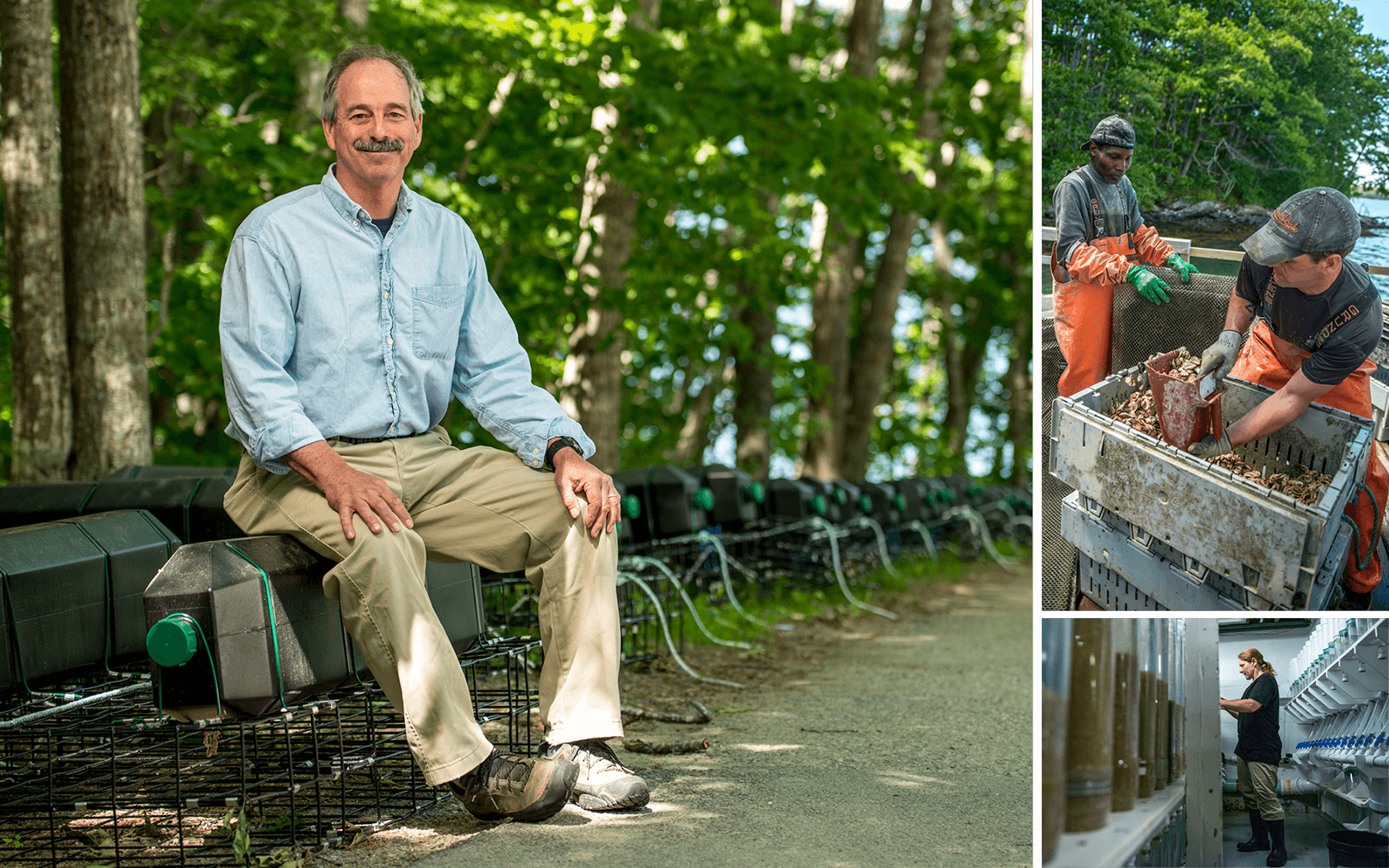

“The work we do here is a very multidisciplinary endeavor. It not only requires a lot of knowledge about oceanography and physics and math and biology, but to be successful, you also have to know how to be a businessperson,” says Bill Mook, owner and founder of Mook Sea Farm and Hatchery in Walpole, Maine.

“I believe aquaculture is one of Maine’s most promising areas for economic development. When you look at the demand for seafood, such as scallops and oysters, and you couple that with Maine’s enormous coastline and wide variety of marine environments, it’s a natural fit,” says Mook.

At the farm, Mook produces over 100 million juvenile oyster seeds annually to sell to East Coast growers. He also raises adult Wiley Point and Pemaquid Point oysters to sell to restaurants statewide.

Mook is using the data collected by UMaine SEANET buoys in aquaculture farms to help understand the changes occurring in the marine environment. Any change in ocean chemistry subsequently affects his oysters’ development.

Mook, who started his farm 31 years ago, is particularly interested in ocean acidification. At the end of the last decade, he started having trouble growing oyster larvae in his hatchery. A colleague on the West Coast told him that ocean acidification may be to blame.

“Because water quality is so important to us, we become an early warning system for problems. What we’ve experienced with larval problems and ocean acidification is a perfect example of that. We are the canaries in the coal mine in that sense,” says Mook.

Ocean acidification is primarily caused by the uptake of carbon dioxide, which dissolves in seawater and increases the acidity, making it harder for oysters to create their calcium carbonate shells.

Because of increased acidity in the Damariscotta River, Mook buffers the seawater flowing through his hatchery to be optimal for oyster development — a reality that sheds a dark shadow on the future of wild oyster populations.

Mook says the buoy data will provide information that will help relate juvenile oyster performance — growth, survival and quality — to changing seawater chemistry.

Mook’s interest in aquaculture was sparked while working on his graduate thesis on benthic ecology at the Darling Marine Center in 1983. At the time, he was working at a commercial shellfish hatchery in Round Pond, Maine, and has worked in the aquaculture industry ever since.

For Mook, it’s not just about growing delicious and locally sourced seafood. He also is concerned with the health of ocean ecosystems.

His oysters are his greatest warriors.

“When you look at the demand for seafood, such as scallops and oysters, and you couple that with Maine’s enormous coastline and wide variety of marine environments, it’s a natural fit.”Bill Mook

“I think there are several important things aquaculture brings to the table for Maine. One is that it is a very environmentally sustainable industry. Oysters are filter feeders; they literally clean the water, so just on a biological level, they really are a good thing,” Mook says.

An oyster feeds naturally on available phytoplankton, filtering 30–50 gallons of water a day. In the process, oysters absorb carbon and filter nitrogen out of the water column. Like carbon, nitrogen is an essential part of life — plants, animals and bacteria need it to survive — but too much has a devastating effect on land and ocean ecosystems.

“There are ways that a lot of these climate change-related seawater chemistry problems can be addressed through research and development that I believe will give Maine opportunities that put it in a favorable com- petitive advantage relative to other New England states,” Mook says.

“The industry is lucky to have the Darling Marine Center right around the corner to help answer these important research questions.”

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, traditionally the world’s supply of seafood has come from wild-caught fish. But in the last 50 years, aquaculture has grown to account for more than 50 percent of the world’s seafood production.

Though Maine is the largest producer of farm-raised marine food in the country, the U.S. accounts for only 0.8 percent of the farmed seafood in the world, a lag which has serious economic impacts. In 2011, the U.S. trade deficit in seafood was estimated to be $11.2 billion, according to NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service.

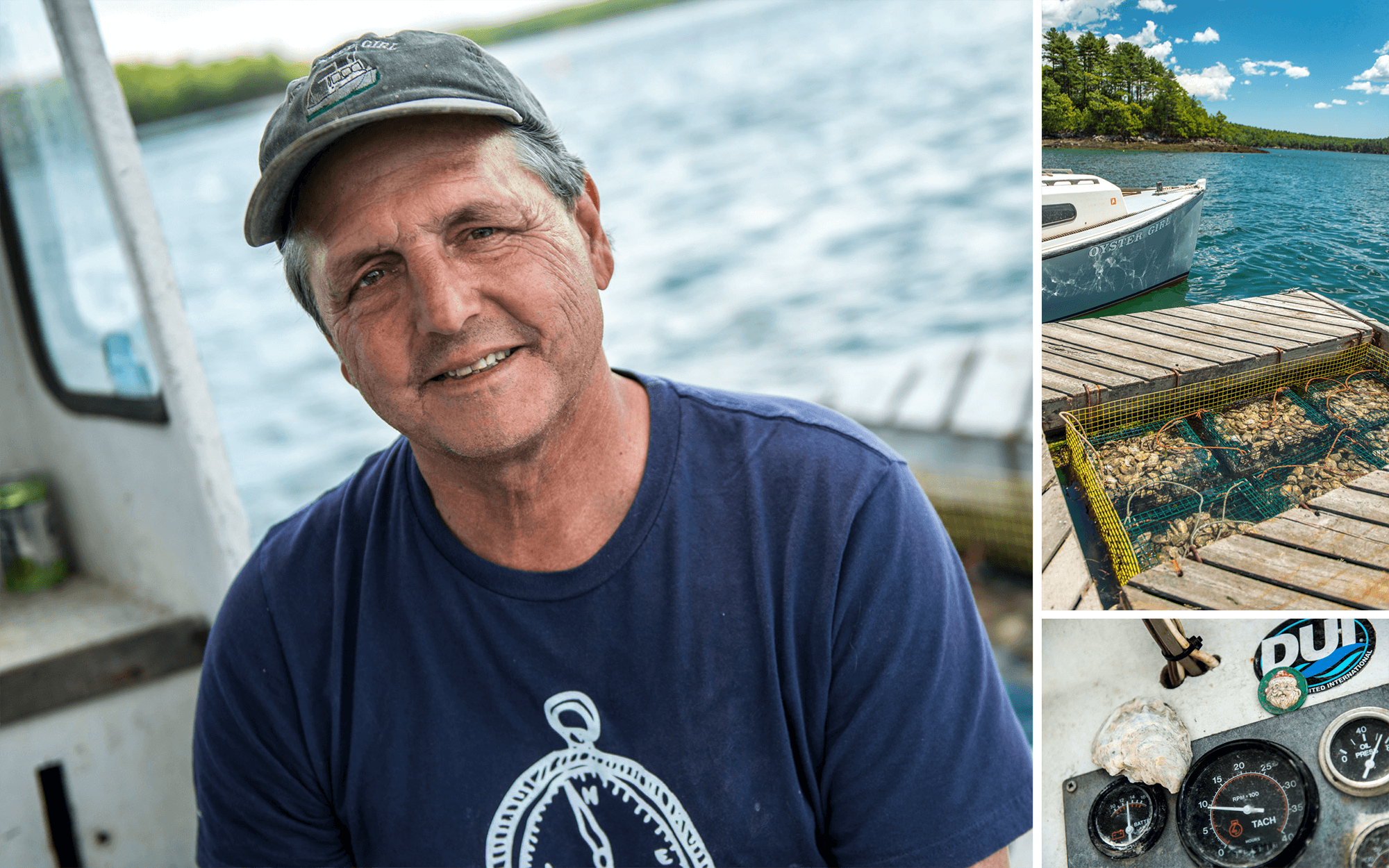

“As the human population continues to grow, we will need more food,” says Carter Newell, president and owner of Pemaquid Oyster Co. and Pemaquid Mussel Farms. “The only way to feed the world is to farm the sea.”

Newell’s interest in aquaculture also was sparked while completing his master’s degree at the Darling Marine Center in 1979, working with soft-shell clams. He decided to start raising mussels and oysters, thinking one of them would fail.

“They both seemed to succeed pretty well,” says Newell as he looks out at his floating farm in Clark Cove.

Newell grows oyster seeds in upwellers and surface trays in the upper Damariscotta and then finishes their development in floating rafts in Clark Cove. Mussels are grown in rafts in Lamoine, Stonington and South Bristol.

His products are distributed to more than 40 restaurants in midcoast Maine, and are shipped to Portland, Boston and beyond.

“As the human population continues to grow, we will need more food. The only way to feed the world is to farm the sea.”Carter Newell

Newell has experience working with shellfish farms in Ireland, where growers rely on government-sponsored buoy systems that have been collecting data for two years.

“It was exactly what we needed to model the growth of the organisms and to really understand the estuary,” says Newell, who now uses data from a buoy in the Damariscotta River to monitor changes in the ocean environment, which helps inform his farming practices.

Specifically, Newell monitors water temperature in the estuaries to know the optimal time to “plant” 2 million oyster seeds.

Though SEANET is focused on understanding what controls the productivity of Maine’s estuaries, the team of researchers also is working to train the next generation of aquaculture scientists, farmers and entrepreneurs.

“Coastal communities in Maine have a strong cultural and economic tradition of working on the sea, and aquaculture is a continuation of this tradition,” says Anne Langston, associate director of ARI.

Though Seth Barker, co-owner of Maine Fresh Sea Farm in Clark Cove, is relatively new to the aquaculture industry, he has a great deal of experience in the field.

“The potential for aquaculture in the state is enormous,” says Barker, who was a marine biologist for the Department of Marine Resources for over 29 years.

“This form of aquaculture is supplying food locally, regionally and even nationally. The potential is not just for nutritious food that can feed the world, but also for jobs and businesses that are related to and tied to the coast of Maine.”

In the clean waters of the Damariscotta River estuary, Barker grows three species of sea vegetables — sugar kelp, winged kelp and dulse — on horizontal ropes. His crops grow through the winter and are harvested in the spring.

“We look at ourselves as being a part of the local farming movement. It just happens that our crops are in the water rather than on the land.”Seth Barker

“In many ways, sea farming is a different slant on farming, but the basics are the same. We’re growing a crop, we have an annual cycle, we have things that any farmer needs to deal with, like pests,” says Barker, who founded his company in 2014 with his partners Peter Fisher and Peter Arnold.

Though the three had different specialties — marine biology, seafood sales and sustainability — they all had a similar vision: to sustainably grow and harvest sea vegetables in a way that supports the natural environment, and protects Maine’s working waterfront and marine-based economy.

Three years later, they are doing just that.

“We’re a small farm,” Barker says. “We look at ourselves as being a part of the local farming movement. It just happens that our crops are in the water.”

Barker became interested in sea vegetables when he saw a demonstration project in Clark Cove to help mussel farmers grow sugar kelp on their aquaculture rafts. The project was conceived by Newell, who had begun seeing kelp growing naturally on some of his mussel rafts. Dana Morse, a Marine Extension associate, was one of the leaders of the demonstration project, funded by the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center at the Darling Center.

Barker uses seedlings grown at the Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research and recently established his own nursery at the Darling Marine Center. He also is collaborating with food scientists in UMaine’s School of Food and Agriculture to look at the shelf life and nutritional value of sea vegetables, and with the Advanced Manufacturing Center on campus to find a mechanized way of drying seaweed.

Barker plans to use the data from the UMaine buoys to better understand the growing cycle of seaweed in the Damariscotta River estuary.

“SEANET not only provides answers to specific research problems, but it also provides people to turn to who are interested in the problems that come along and questions that need to be answered within the aquaculture industry,” Barker says.

“The better we can connect sea farmers and researchers, the further along we will move in developing this form of farming. The potential of what we’re doing, I’d like to say, is huge. And I’d like to say we will feed the world.”

Some of Maine’s biggest aquaculture fans can be found in downtown Portland at Eventide Oyster Co. The intimate oyster bar features warm natural lighting, picnic table seating, and extravagant and inventive seafood dishes, spirits and local beers. The menu bursts with creative dishes, but there’s no doubt what’s the star of the show — fresh Maine-grown oysters offered raw on the half shell.

Chef and owner Andrew Taylor says the expansion of aquaculture in Maine would not have been possible without the public’s interest in locally grown food. He has been amazed by the support of locally grown shellfish since his restaurant opened in 2012.

Taylor, named the 2013 Best New Chef in New England by Food & Wine magazine, is one of many chefs who partner with aquaculture growers across the state to provide customers with the freshest possible seafood on the market.

“When we opened this restaurant, it was our goal to showcase some of the best oysters and shellfish in the world,” says Taylor. “The best oysters are the ones that are grown closest to home, right here off the coast of Maine.”