Reflecting on ecosystem-based management

Last week, I participated in a symposium at the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) annual meeting in Boston, Massachusetts. This is an impressive scientific society, including more than 120,000 members from the US and 90 other countries around the world.

I am particularly appreciative of AAAS as they hosted one of the first meetings I attended as a graduate student. I also am honored to be recognized as a AAAS Fellow.

I went to Boston in anticipation of seeing old friends and colleagues, and meeting new ones. Together with colleagues from other universities and one of the US’s leading scientific federal agencies, NOAA, I shared my reflections on the science and practice of marine ecosystem-based management during one of the meeting’s scientific sessions.

My goal was to highlight how far we have come with the science and the implementation of ecosystem-based management for our coasts and oceans and also, the highlight the work that still needs to be done, in which we all have a part. You can view my presentation slides here.

I focused my remarks on the Gulf of Maine, a highly productive and cultural and economically important bit of the world ocean just beyond my doorstep. Over 3300 species marine plants and animals can be found in Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank, including over 650 species of fishes, 32 marine mammals, and 180+ species of seabirds. This tremendous biodiversity is supported by the Gulf’s dynamic and seasonally shifting oceanography (NOAA 2025).

I am a child of the Gulf. I grew up in Plymouth, near Cape Cod. And I now live on the Maine coast, an hour east of Portland. Like many New Englanders, my family and I spend a lot of time close to the water, swimming and walking by the shore, sailing, and watching birds. And for work, I have closely studied the varied connections between people and the ocean in this region, including coastal fisheries.

These connections between people and the ocean are the foundation of ecosystem-based management. They are what enable us to identify the place-based goals that guide both the science and practice of ecosystem-based management.

My main message to the AAAS audience was that the science and practice of ecosystem-based management have evolved a lot in the last 25 years. That is large part to the tremendous efforts of scientists, including many of our federal scientist colleagues at NOAA.

Around the turn of the century, single issue management was the norm at the federal, state and local levels in the US. That is how many of our landmark laws are written – think the U.S. Endangered Species Act that guides protection of the piping plover, for example.

I saw this firsthand, when I was active in piping plover research 30 years ago as a college intern with the Massachusetts Audubon Society. The management focused on the birds and creating conditions on Massachusetts’ barrier beaches to increase the success of individual pairs to fledge chicks. Sea level rise, beach and marsh restoration, and even the behavior of people who share beaches with these birds were outside the scope of plover management in the mid 1990s. Yet this bird is part of a much bigger coastal marine ecosystem.

Also, people were not part of many folks’ concept of an ecosystem. When people were considered, they were external to the system, and usually impacting it in a negative fashion.

Policies began to shift in the early 2000s with the release of the Pew Ocean Commission report and the National Ocean Commission report. Both reports identified ecosystem-based management as vital to our nation.

The progress continued with the National Ocean Policy released in 2010.

NOAA has been developing the science and policy of ecosystem-based management for more than 25 years. With the release of the EBFM roadmap (2016, and updated in 2024), that work became more visible and useable by managers, scientists, and others working at the regional and local levels.

Along with these policy developments, the science also has evolved. In my AAAS talk, I focused on the science of social-ecological systems specifically. When I talk about this science, I am talking about interdisciplinary research that embraces the connections between people and nature; recognizes the value of multiple disciplines and ways of knowing, including local and indigenous knowledge; and contributes to solutions.

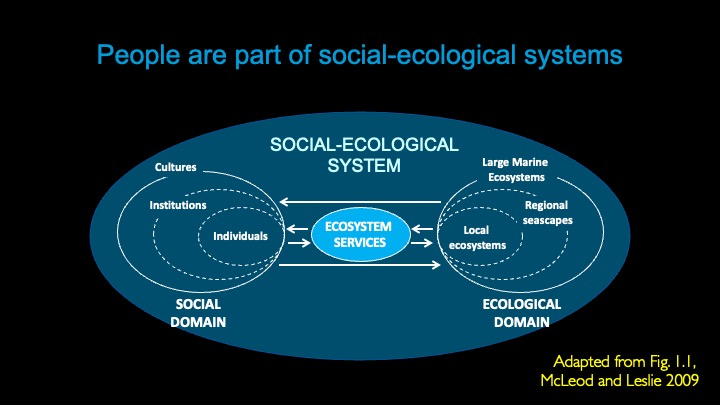

Social-ecological systems approaches recognize that people are part of the ecosystem.

This figure from the book that Karen McLeod and I edited, Ecosystem-Based Management for the Oceans (Island Press, 2009) illustrates these connections. We can see the hierarchical connections among ecological elements of the system, and also within the social domain. And we can see that the domains are connected, in multiple ways, often through ecosystem services like fisheries and recreation.

If you flip through my presentation, you’ll see the two examples I shared of how the science and practice have evolved. First I talked about a regional example: NOAA’s Integrated Ecosystem Assessment process in the Gulf of Maine. Then I discussed our lab’s work in the Damariscotta River estuary in coastal Maine.

Through these two examples, I argued that by bringing together knowledge of the diverse connections of the system of interest, we create more robust information and understanding. This way of doing ecosystem science supports a more varied set of management strategies than we get if we just rely on assessments of a particular species or set of human activities in a place. Place-based connections matter.

In summary, the science and practice of EBM has evolved a lot in the last two decades. This progress has supported implementation of EBM at multiple geographic scales.

However, we still have work to do! To guide future management, we need to continue to monitor and document the impacts of ecosystem-based management and other drivers on nature and people. If this is something you are interested in collaborating on, please be in touch.

Thank you for reading.

Heather