Marine ecology on the Maine coast

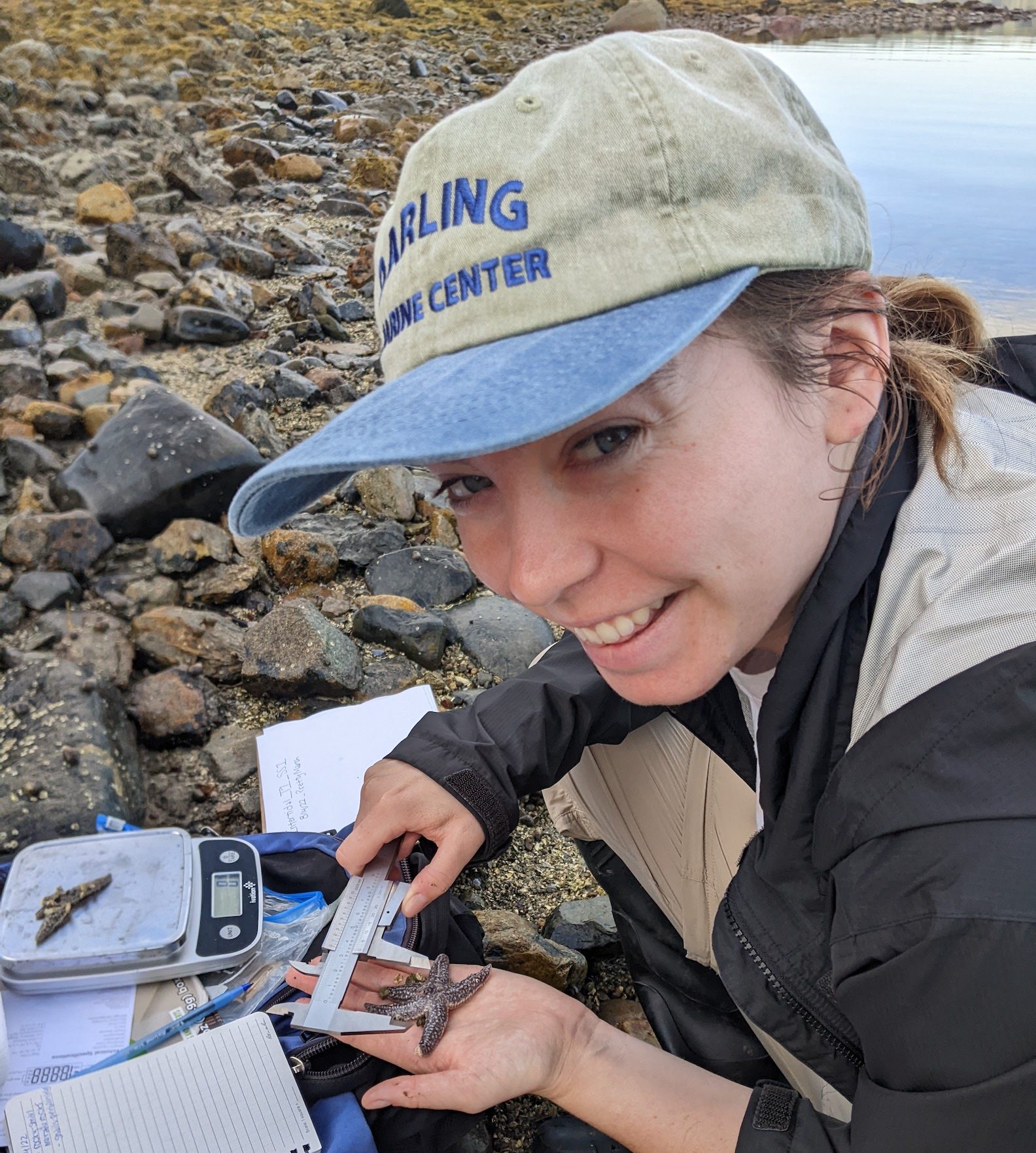

Sophia Pelletier served as an undergraduate research assistant in the Leslie Lab at UMaine’s Darling Marine Center in summer 2022. She is from San Diego, CA and currently lives in Davis, CA. Sophia graduated from University of California at Davis with a BS in Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology and is applying to graduate programs in marine ecology.

Getting Started

This summer, I was fortunate enough to work as an undergraduate research assistant in the Leslie Lab. I came across this opportunity via the Mark D. Bertness Grant to Support Marine Field Ecology in Maine offered by the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center. My senior year at UC Davis, I felt behind in my research experience due to the pandemic. While I didn’t immediately write a proposal, I kept it in the back of my head throughout the fall. After returning from winter break, I decided to give this proposal my best shot.

I started drafting ideas. I spent hours on my floor, reading scientific papers and mapping out ideas until I ultimately came up with a study to investigate sea star population change over time in the Gulf of Maine. I discovered a program led by the Schoodic Institute, inviting citizens to document sea stars along the Maine coast. I was initially drawn to this call to action because it stated: “Upload the pictures to iNaturalist, a smartphone app for collecting and sharing nature observations…” I knew that I wanted to incorporate citizen science into my research proposal, and iNaturalist is a good platform for mapping the current distribution.

Launching the Research

The first step was to read literature and familiarize myself with sea stars and the coastal marine habitats of the Gulf of Maine. The next step was creating an answerable research question for the summer. Following a literature search, I found that a lot of the questions I had (i.e., why are sea star populations declining?) were not answerable in a summer. I needed to ask a question that I could have at least a preliminary answer to by the end of the summer.

My initial question for the summer was: How have sea star abundances changed over time? However, as I learned more about the system and the work others had done, I developed two more specific questions:

- What are the current distributions of various sea star species in the Gulf of Maine?

- How have blue mussel (Mytilus edulis), the primary prey of Asterias sea stars, abundances changed over time in the Gulf of Maine?

Connecting with Others

Contacting experts was one of the most inspiring parts of this project. I got to have amazing and educational conversations with experts, divers, community members, and graduate students. I was fortunate to meet Melina Giakoumis, a graduate student at the City University of New York. Melina had conducted intertidal and subtidal sea star surveys in the Gulf of Maine the summer before and asked if I would be interested in using her protocol and sites from the previous summer. This was a breakthrough. Once I had the protocol for quantifying sea stars, I was able to think about other data I would like to collect while in the field.

After I met with Melina, I took the time to think about what I had learned and how I wanted to translate that knowledge into my surveys. My goal was to get the most out of my sampling, despite limited time. I ultimately decided to add mussel percent coverage and algae percent coverage.

I added mussel percent coverage for two reasons: (1) mussels are a prey source for sea stars and (2) during a community meeting, one of the coastal land owners asked us why mussels are declining. This question struck a chord with me, as someone who lives on the coast is seeing these changes and wants to know why. Documenting these changes is the first step to understanding the cause.

I added algae percent coverage because the second time that I surveyed at Chamberlain (also known as Long Cove Point), I observed extensive algae coverage. These surveys were as a part of an experimental survey approach, so I had the freedom to add what I wanted to monitor. In addition, I took note of water temperature and salinity at each of my sites.

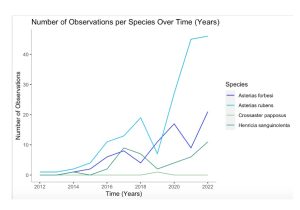

Sharing my Science

At the end of the summer, I gave a poster presentation at the SEA (Science for Economic Impact and Application) Fellows Symposium at the Downeast Institute in Beals, Maine. I spent a lot of time making graphs and deciding what would best summarize all that I learned over the summer. This symposium was the first time I had the opportunity to present my own project. This was a pivotal moment for me—I felt confident in what I had done this summer and in my ability to present and answer questions about my research. This graph (Figure 1) on my SEA Fellows Poster received a lot of attention. It was complemented by a figure created by the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR) which showed that sea stars censused subtidally on the Maine coast have declined drastically within the last 20 years. Many people asked me why there appeared to be an opposite trend on my iNaturalist graph, which largely reflects intertidal observations, as compared to the DMR figure. While I believe that platforms such as iNaturalist can and will be important for long-term monitoring in the future, there is a lack of earlier data (i.e., 2012) as compared to 2022. This is because more people now have access to phones and the internet, and iNaturalist is more widely known and used, leading to more data.

Reflecting on the Research Experience

This summer was not only a great experience conducting independent research, but also enable me to develop confidence in myself as a scientist. I could not have succeeded without the help and support of my lab mates, collaborators, and faculty mentor, Dr. Heather Leslie. My undergraduate mentors from UC Davis also provided key support and insights.

Through my work in Maine, I was able to take a big step in my journey as a scientist: I was able to design my own research project. Designing my own project presented me with an amazing opportunity to develop skills in sampling design, data collection, and analysis. This was especially important given that I lost out on years of in-person research experience due to the pandemic. The pandemic took away human contact, which resulted in a loss of networking opportunities. This meant a loss of potential lab and field opportunities, and also an added difficulty to build professional and academic relationships important for letters of recommendation and mentorship. This summer, I was fortunate enough to meet with many researchers and these conversations gave me valuable experience networking and building important professional relationships.

Sophia’s research experience was supported by friends and supporters of the Darling Marine Center, and specifically a Mark D. Bertness Grant to support Marine Field Ecology in Maine as well as additional funds thanks to a faculty grant to Prof. Heather Leslie from the Henry David Thoreau Foundation. To learn more about undergraduate research opportunities at the UMaine Darling Marine Center, please contact Prof. Leslie at heather.leslie(at)maine.edu or visit the DMC website at https://dmc.umaine.edu/. If you would like to support undergraduate research at the DMC, we would welcome your support; details on giving are at https://dmc.umaine.edu/giving/.