Maine Schools in Focus: How Far Have We Come? Looking Back a Century

Editor: Gordon Donaldson

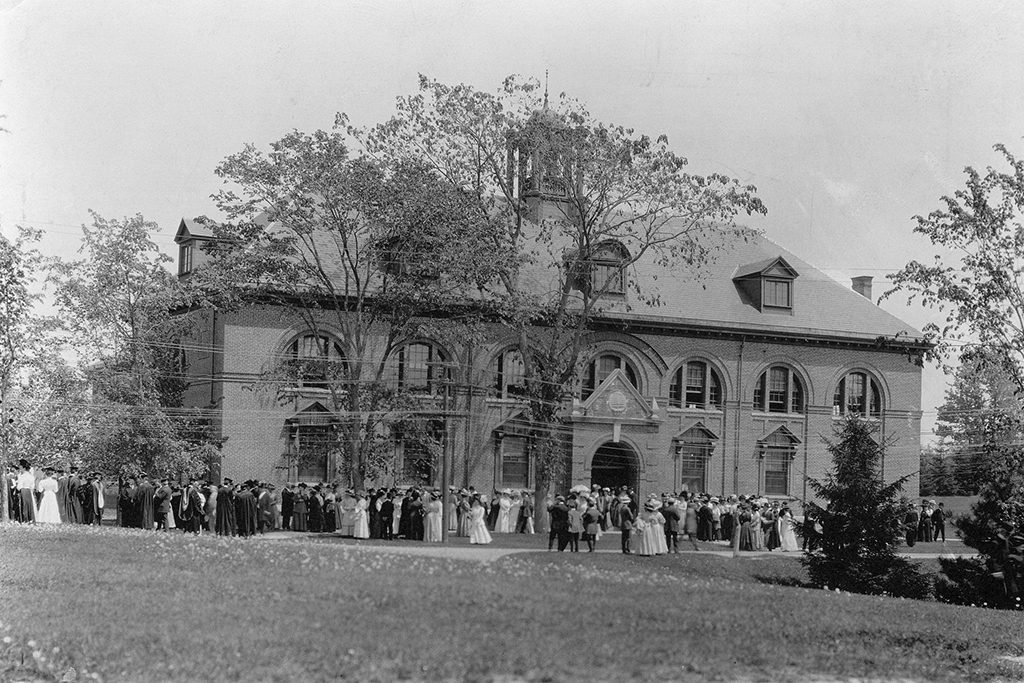

The turning of the new year prodded us to look back in time for some perspective on Maine schools in 2017. The annual “state of the schools” report for 1915-16 (Waterville, 1917) offers a few perhaps useful observations.

Glenn W. Starkey, State Superintendent of Public Schools at the time, commended the state on the “growth… and greater efficiency” of our schools. But he also warned of “the necessity of increased effort and the setting of higher standards” (p. 6). The growth he referred to was in the numbers of “pupils” registered and attending Maine schools: 68 percent of school-aged children, 5-21, were registered in school. Only 53 percent of school-aged children, though, attended regularly (average daily attendance). The “higher standards” Starkey sought were in the length of the school year, the training and quality of teachers, teacher pay, and the standardization of curriculum and “school quality,” especially in the emerging secondary schools.

One-hundred years ago, Maine children were served by roughly 4,000 neighborhood Common Schools (2,353 of them were one-room schools) and 250 secondary schools (199 free high schools and 51 academies). In 1916, teacher turnover was a huge issue: in the course of a year, twice as many teachers taught in Maine schools as there were teaching positions (on average, a 100 percent turnover rate). Ninety-three percent of Common School teachers and 65 percent of secondary school teachers were women. This was true despite the fact that, at an average annual salary of $486, men earned $105 more than did women in Common Schools; and in high schools and academies, men earned an average of $450 more than women (the average salary for men was $1,065).

In 1917, the Office of the Superintendent of Public Schools (staffed by eight people) had for 20 years sought to wrestle this far-flung, locally-controlled non-system into a “higher quality, more efficient, modern” system of education. Schools were to follow the state’s prescribed “courses of study.” (In fact, a few widely published series of textbooks dictated what kids learned.) Superintendent Starkey wrote of the growing number of school buildings that were “not conforming to accepted standards” and of the many rural schools that needed a “campaign of improvement” assisted by the two “rural agents” employed by his office (pp. 8-9). He applauded the work of Josiah W. Taylor, the “secondary school agent,” who traveled to high schools for their “annual inspection,” particularly focusing on the “small class A schools” with two teachers (p. 11). Taylor spent a day at each school that included “a conference with teachers on matters of classroom management, content of courses and general school activities.” (We’re unclear if he traveled by auto or by horse!)

Starkey saved a special place to discuss the “system of professional supervision through unions of towns” that the Legislature and his office had been promoting since 1893. He applauded the fact that, now, 319 towns had “professional superintendents,” surpassing the 209 towns served by elected “local superintendents.” He pointedly noted that 190,321 students were served by schools with “professional supervision” compared to only 35,916 with “local supervision” (p. 20). By “professional supervision,” Starkey meant a state-approved superintendent of a School Union formed by towns jointly employing the superintendent—Maine’s first form of regional district. He rued the fact that some towns had not joined unions and that others who wanted to could not because of their location. He predicted that “legislation in the immediate future” would address this issue. A year later, all towns were mandated to join Unions and all Unions were required to employ full-time superintendents.

In 2017, there are few if any vestiges of the rudimentary system of 1917 in Maine. Every child of school age must now register for school. Our public schools educate roughly 90 percent of these children. We have just a fraction of the school buildings we did then. Almost 80 percent of our students are bussed to school instead of walking. Teaching has grown into a stable profession. Schools can depend on continuity of instruction and personnel, for the most part. Inequities in pay for men and women and elementary and secondary teachers have largely disappeared. The quality of school buildings is less of a concern (although paying for them and their increasingly varied contents is more contentious than it was in 1917). Our current preoccupation with outcome measures, proficiencies, and accountability was only a faint concern 100 years ago, when the preeminent concern was getting kids to come to school at all and providing them with a qualified, dependable teacher!

Gone are the days of neighborhood schools governed by neighborhood and town school committees with “non-professional” superintendents. We now live and work in a school system governed and administered by a legislature, department of education, and regional school districts that insert authority into Maine’s schools far more than Superintendent Starkey ever dreamed. That system is far more politicized through professional associations, interest groups, and lobbying than it was a century ago. But the variety of types of school district in Maine and the persistent numbers of homeschooled and private-school children remind us that there are natural limits to how far the system can extend.

Yet, as 2017 dawns, we find a number of the sentiments and concerns from 1917 to still resonate.

- Above all, Starkey and his staff asserted a concern about “quality” and “standards.” The report enumerates ways that local schools could improve. While state mandates threatening to withhold funding had not entered the scene, Starkey clearly saw his role as advocating greater professionalization of the entire schooling enterprise.

- Attention was focused on teachers, on ways to support them and to improve their performance. In 1917, it was higher wages, more “teacher conventions” and “summer institutes,” and more available training in the Normal Schools. Today, it’s a richer array of professional development partnered with a more highly structured system of performance review and accountability.

- The tenor of public education a century ago reflected an overarching hopefulness and faith in the enterprise. Superintendent Starkey and his staff wrote in 1917 about “possibilities for more extensive cooperation,” of “campaigns for improvement,” and of the dedication of teachers despite low pay and difficult working conditions. Today, optimism may be in shorter supply than in 1917, but the vital roles of positive culture, of expecting the best from every child, and of teacher voices in leading our schools are widely supported and enacted.

- There persists a healthy tension between government’s role in schools and that of local educators and citizens. In 1917, citizens and teachers determined what happened in schools. In 2017, that is ultimately still the case, but district, state, and federal influences have a far stronger role.

Perhaps, in this last respect, we can carry into 2017 the words of Harold A. Allan and Florence M. Hall, State Agents for Rural Education, who wrote: “[We] have at all times endeavored to impress on school officers the fact that [our] work is not inspectory in type but that [we] wish to cooperate and serve as expert helpers and advisors to those in charge of schools” (p. 39).

Sources: “Report of the State Superintendent of Public Schools for the State of Maine, 1917 (The Sentinel Press: Waterville, ME)

Maine Schools in Focus is intended to share information that stimulates thinking, planning, and action to fulfill the mission of Maine’s preK-12 schools. Submissions must present ideas and data relevant to schooling in Maine and pose questions and suggest avenues for policy and action. They must be limited to 750 words.

Contact: Gordon Donaldson at gadjr11@gmail.com.