Less (care) is more (carbon)? Exploring increased passenger vehicle emissions associated with hospital maternity unit closures in Maine

By Gianna DeJoy

Abstract

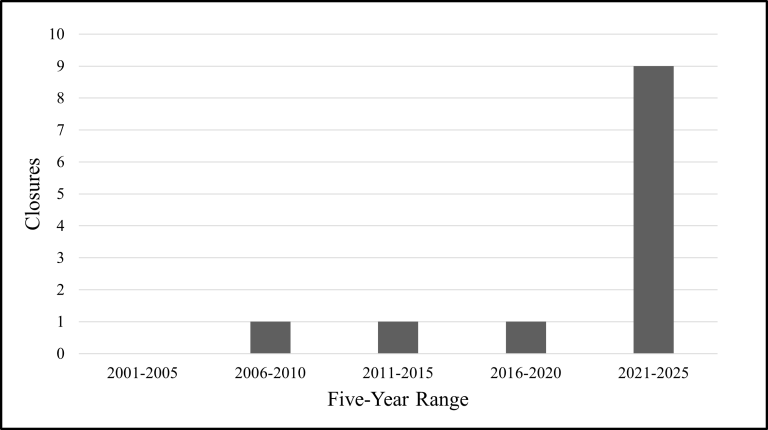

Twelve Maine hospitals have ceased offering obstetric services since 2009 – nine since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, large swaths of the state are over an hour-long drive from the nearest hospital with a maternity unit. While the health and community impacts of maternity unit closures are being documented more and more, less attention has been directed to possible environmental ramifications. This paper is intended to begin that conversation by providing a rough estimate of passenger vehicle carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions associated with the increased travel burden for obstetric patients following three Maine maternity unit closures. I estimate that the closure of three hospital-based maternity units in 2023 could have equated to adding 14 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles to Maine roads over the following year. Together, these closures may have led to an extra 60.07 metric tons of climate-warming CO2e emissions resulting from additional mileage driven by pregnant people seeking care. I call for further research on the environmental dimensions of (reproductive) healthcare access and suggest consideration of alternative models of maternity care that may be more environmentally and socially sustainable.

Introduction

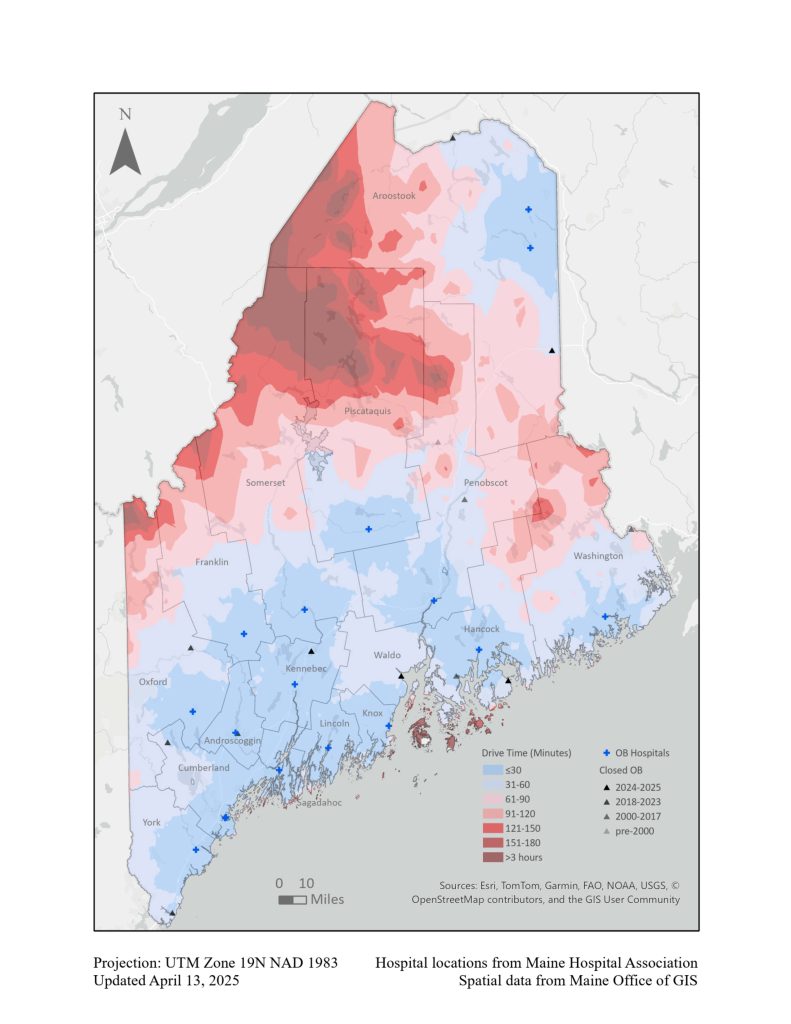

Twelve Maine hospitals have ceased offering obstetric services since 2009 – nine since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). As a result, large swaths of the state are over an hour-long drive from the nearest hospital with a labor and delivery (L&D) unit1 (Figure 2). This rapid erosion of hospital-based obstetric services has significant implications for the health and wellbeing of impacted communities. Living a long distance from care represents a significant barrier to accessing both acute and routine, preventative reproductive health services (DiPietro et al. 2021). Both living far from care and losing a local provider are associated with higher risk for a range of adverse outcomes for pregnant person and infant, including unplanned out-of-hospital birth, preterm birth, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, and maternal mortality (Kozhimannil, Hung, & Henning-Smith 2018; Minion et al. 2022; Wallace et al. 2021). Additionally, when a community loses health services, there are impacts beyond those on the immediate patient population; people lose their jobs, community morale is affected, and medical mistrust can be exacerbated (Klein et al. 2002; Statz & Evers 2020).

While the health and community impacts of maternity unit closures are being documented more and more, less attention has been directed to possible environmental ramifications. This paper is intended to begin that conversation. Here, I use hospital data and carbon footprint and greenhouse gas equivalency calculators to estimate additional carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions resulting from extra miles driven by obstetric patients seeking hospital care in the aftermath of three Maine maternity unit closures. Further consideration of potential environmental impacts and mitigation strategies follow.

Background

Rural maternity care is in steep decline across the country. Following centuries of effort by the medical establishment to eradicate traditional midwives and foster dependence on obstetricians and hospital birth, the centralization of hospital-based care has left millions of U.S. women living in counties with no midwifery or obstetric services (Stoneburner et al. 2024). While hospital-based obstetric services have been centralizing to population hubs for decades, in more recent years smaller hospitals have begun to shutter their maternity units at a faster rate. Even in 2012, less than half of rural U.S. women lived within a 30-minute drive of the nearest hospital offering obstetric services (Hung et al. 2016). Between 2006 and 2020, over 100 rural hospitals and 400 hospital maternity units closed their doors (Simpson 2020; Sonenberg & Mason 2023). The most remote areas experienced the greatest loss in local obstetric services. Today, over half of rural U.S. counties have no hospital-based obstetric services (Kozhimannil et al. 2020). The result is a significant “travel burden” for rural parents: that is the time and distance spent travelling to access care.

Scholars have previously pointed out that modern birthing people can face a suffocating “double discourse” (Gurr 2015). Both science and the state work to monitor and manage every stage of the reproductive life course, especially conception through birth. Public concern surrounding the maternal-fetal transmission of toxicants has put pregnant and parenting individuals’ actions under the microscope (see Lappé, Hein, and Landecker 2019; cf. EWG 2005). In the U.S., the overturn of Roe v. Wade opened the door to new levels of reproductive surveillance and the criminalization of pregnancy outcomes. Meanwhile, there is stark medical neglect. Instead of experiencing care in medical settings, patients too often have their preferences ignored and concerns brushed aside; those on the rural periphery face an increasingly sparse healthcare landscape; and marginalized communities struggle to access quality, culturally appropriate reproductive health services even in more metropolitan areas. This is what social scientists call “stratified reproduction” (Colen 1995). While the U.S. has the highest maternal death rate overall of all high-income countries – more than double that of Canada – Black, Indigenous, low-income, and rural populations are disproportionately affected. Non-Hispanic Black and Indigenous individuals are three to four times more likely than non-Hispanic white individuals to die of pregnancy-associated causes (Gunja et al. 2024; Kozhimannil et al. 2020). Maternal mortality is nearly two times higher in rural compared to urban areas (Harrington et al. 2023). Disparities persist in severe maternal morbidity (potentially life-threatening childbirth complications) and infant mortality (Ehrenthal et al. 2020; Jang & Lee 2022; Kozhimannil et al. 2019; Kozhimannil et al. 2020). In this context, the dual forces of control and neglect can be viewed as a tacit elimination strategy for certain populations, selectively impeding social reproduction (Gurr 2015; Nelson 2011).

Climate change is another leading threat to social reproduction as it impacts human health across the lifespan. Pregnant and postpartum people and their infants are among the vulnerable populations facing unique and added risks. The World Health Organization (2023) suggests that climate hazards such as extreme heat may be associated with increased risk of developing pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Longer, hotter heatwaves, air pollution from wildfire smoke and fossil fuel emissions, and other climate disasters are associated with preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth (Bekkar et al. 2020; Harville et al. 2021; Kuehn & McCormick 2017; Maher, 2019). Climate change also brings the promise of more prevalent viral, zoonotic, and vector-borne diseases2 that are especially dangerous for people with compromised or developing immune systems like pregnant people, infants, and young children (Maher, 2019). Additionally, when social conflicts or stress arise as a result of disasters or resource scarcity, women and children bear the brunt of downstream effects like gendered and sexual violence (Maher, 2019; WHO, 2023). All these threats can overlay and exacerbate preexisting health disparities.

As healthcare systems grapple with these growing harms, they are also large producers of greenhouse gas emissions, excess waste, and other pollutants. One analysis estimated that the Canadian healthcare system’s greenhouse gas and other pollutant emissions are linked to an annual loss of 23,000 “disability adjusted life years” (years of poor health, disability, or early death) in that country (Eckelman, Sherman, & Macneill 2018). The U.S. healthcare sector accounts for up to 10% of national emissions (Mercer 2019). The specific environmental footprint of obstetrics and gynecology is understudied, but one systematic review found room for significant mitigation through reducing reliance on single-use health and hygiene products3 and making energy efficiency improvements in obstetric and gynecological surgery (Cohen et al. 2023).

Telehealth is often suggested as a means for addressing both issues associated with travel burden: vehicle emissions and poorer health outcomes (Cohen et al. 2023; Hung et al. 2023). Of course, when it comes to maternity care, telehealth can only help mitigate travel burden for prenatal and postpartum patients; a video call cannot replace skilled, hands-on assistance during birth. Beyond the evident limitations, Hung et al. (2023) found that U.S. communities located farthest from care facilities also had the least digital access, representing “dual barriers” to care for the most disadvantaged families. Telehealth must be viewed as an (incomplete) stopgap measure for centralizing maternity care rather than a silver bullet.

Methods

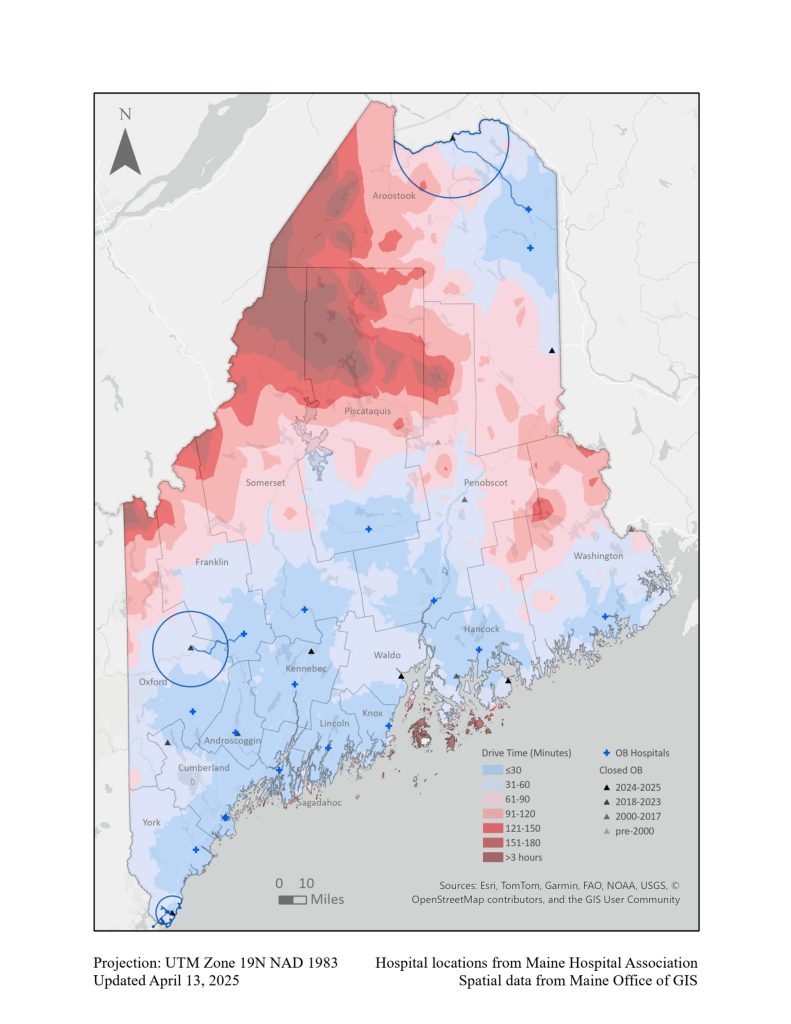

This exploration takes as example the three maternity unit closures that occurred in Maine in 2023; those of Northern Maine Medical Center, Rumford Hospital, and York Hospital. Northern Maine Medical Center is an independent acute care hospital located on the Maine-New Brunswick, Canada border in the town of Fort Kent (Aroostook County). Rumford Hospital, in the town of Rumford (Oxford County), is a critical access hospital associated with the Central Maine Healthcare system. York Hospital, in the town of York (York County), is an independent acute care hospital affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital, located very near the Maine-New Hampshire border. These cases represent closures in northern, western, and southern Maine, respectively (Figure 3).

Results

I found that the combined additional mileage would have generated about 60.07 metric tons of climate-warming CO2e emissions4 over the year following the closures. There are inherent shortcomings of equivalency calculators and of the very attempt to translate obstetric travel burden into carbon emissions, which are discussed further in the following section. Recognizing the over-simplifying nature of such a task, these estimated emissions nonetheless warrant some illustration. According to the EPA, the release of 60.07 metric tons of CO2e is equivalent to adding 14 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles to Maine roads that year or filling up a sport utility vehicle’s5 gas tank about 407 times (Table 1). That is the amount of CO2e emissions generated by consuming 139 barrels of oil. It is also the amount of carbon sequestered by 60.3 acres of forest in one year. These estimates represent the possible impact of just one state’s maternity unit closures in a single year – a small snapshot out of the hundreds of closures that have occurred nationally over the past decade.

| Closure | Estimated additional mileage associated with closure | CO2e emissions associated with estimated mileage | Gas consumption equivalent | Additional gas-powered passenger vehicle equivalent |

| Northern Maine Medical Center | 52,509.6 miles | 15.9 metric tons | 1,789 gallons | 3-4 vehicles |

| Rumford Hospital | 50,342.4 miles | 15.24 metric tons | 1,715 gallons | 3-4 vehicles |

| York Hospital | 95,529.6 miles | 28.93 metric tons | 3,255 gallons | 6-7 vehicles |

Limitations

The calculations provided here are preliminary and include significant limitations. I made several simplifying assumptions, including that patients aren’t crossing the border to seek care in Canada, that no patients drove electric vehicles (EVs), and that obstetric patients didn’t choose to split their care (i.e. see a family practitioner for prenatal care at one facility and deliver at a different facility). I don’t know the actual addresses of the hospitals’ patients and I didn’t thoroughly investigate the population size or demographics of the various localities in order to more accurately estimate health facility catchment areas, patient numbers, and drive times. Another limitation is that birth counts don’t account for patients who made trips to the hospital to receive prenatal/obstetric care but didn’t give birth – that is, pregnancies ending in later abortion or miscarriage. Additionally, in these calculations I only had 2020 hospital survey data available. If more recent birth counts (from 2021 or 2022) were significantly different, they would have produced different mileage totals and therefore different emissions numbers. All these limitations should reaffirm the imprecise, exploratory nature of the estimates provided here.

There are also limitations to the very idea of the carbon footprint. In the process of reducing complex, contingent situations and deeply felt experiences – in this case, those of families seeking care in a sparse and shifting medical landscape – to formulas and numbers for the sake of comparison, we risk losing context, nuance, and empathy (Isenhour, O’Reilly, & Yocum 2016). With growing awareness of the climate crisis, personal carbon footprints have been assigned not only to living individuals but also to their potential offspring. One consequence of this kind of thinking is a brand of “eco-natalism” that shames others for their reproductive choices or even explicitly seeks population reduction strategies (Rush 2023; cf. Haraway 2015). This is an example of models and quantifications being granted outsized power to the extent that they overshadow lived realities and obscure other possible futures. In this light, I hope that my calculations are understood to be neither objective nor apolitical. While I did make choices to avoid falsely inflating emissions estimates, the very act of creating them was undertaken with subjective intent: to draw wider attention to the fact that healthcare access and climate change are not siloed issues.

Discussion

It is important to emphasize that this paper only explored patient passenger vehicle emissions rather than attempting a holistic ecological footprint analysis. Consistent with this narrow scope, I didn’t account for hospital staff and provider drive times that may have been impacted by the maternity unit closures (e.g., did former employees find new jobs with longer commutes or stay at home following the closure?). I also didn’t attempt to estimate or make commensurable the energy savings and reduction in medical waste that likely resulted from the three maternity unit closures. As previously noted, from facility demands to single-use medical supplies and anesthetics, obstetric practice is resource intensive. It is entirely possible that, all told, even a rural hospital’s decision to shut down its L&D unit has more positive than negative environmental effects, despite the travel burden imposed on its obstetric patients.

For this very reason, the solution to the complex issue of vanishing maternity care – and its attendant environmental considerations – cannot be to force the establishment of more hospital-based L&D units, especially in places where they have already been demonstrated financially or logistically unsustainable. Policymakers and health system administrators should certainly prioritize “stopping the bleed” of obstetric services. There are already efforts underway to train and recruit more providers to practice in rural areas. Other meaningful policy actions on this front might include raising Medicaid rates for maternal health services provided in federally designated Maternity Care Health Professional Target Areas (MCTAs); offering at-risk maternity hospitals a standby capacity payment to keep their L&D units open; or requiring a set public notice period and specific protocol (such as ensuring all patients’ adequate transfer of care) before hospitals end maternity services (see CHPQR 2024 and Snipe 2023). However, a longer-term vision should be of alternative models of maternity care that are designed to serve smaller and more dispersed populations – and to be more environmentally friendly.

Midwife-led, community-based birth centers, for example, can operate with lower overhead costs and – if they are reflective of the populations they serve – a high level of local buy-in and support (e.g., Van Wagner et al. 2007 and Karbeah et al. 2022). They also require fewer staff, which is significant as staffing shortages are among the most cited reasons for maternity unit closures (Hung et al. 2016; Kozhimannil et al. 2022). Hospital-based L&D units require on-call anesthesiologists in addition to obstetricians, L&D nurses, etc. A birth center or homebirth midwifery practice can have exactly as many providers as the community demands, down to solo practitioners. We might imagine a future where every community holds its own birth center or homebirth midwife and, as a result, maternity care close to home is the default option. Policymakers could bring us closer to this future by addressing restrictions on direct-entry and nurse-midwives’ independent practice and ensuring the care they provide is adequately reimbursed by both public and private health plans. New birth centers could also be granted an expedited and/or discounted Certificate of Need application process, exempting them from some of the more burdensome bureaucratic requirements that can keep smaller providers out of the market (see Snipe 2023).

Midwives have a long tradition of skillfully filling gaps in rural medical infrastructure (Dawley 2000). Research reliably shows midwife-attended community birth to be as safe as hospital birth (with superlative outcomes in measures like c-section rates and maternal satisfaction and empowerment) even in rural settings (Cheyney 2008; Davis-Floyd et al., 2009; Jolles et al., 2020; MacDougall & Johnston, 2022; Nethery et al., 2018). In their study on the role of birth centers in building rural health infrastructure and community resilience, Jolles et al. write that “as the infrastructures of standard, hospital-based maternity care in rural communities deteriorate, the birth center model of care has demonstrated its role as a durable model capable of stable and predictable capability to provide high-quality health care” (2020, p. 433). The case of Inuit communities that have successfully “rematriated” birth after decades of maternal evacuation policies – including creating local midwifery education programs – shows that community-based and culturally-centered maternity care can improve outcomes even in the most remote settings (Van Wagner et al., 2007; 2012). In Maine, a robust network of local providers could work closely with existing higher-level obstetric facilities and medical transport services, ensuring fast and efficient interprofessional collaboration and/or transfer of care in the case of higher-risk pregnancies or emergent complications; a type of regionalization strategy focused on making abundant care6 a reality for rural communities.

A turn to community-based maternity care could have environmental benefits beyond reducing reliance on fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Compared to a hospital L&D unit which is generally “on” 24/7, including an equipped operating room, a community birth center can easily run in a more energy efficient manner (Cohen et al., 2024). This is as simple as the fact that birth centers are typically smaller facilities with fewer electronic devices and can turn off the lights when no patients are present. Further, the midwifery model of care that operates in community birth centers is broadly understood to be more environmentally friendly than the technocratic model typically seen in hospital settings (Davis-Floyd 2001; O’Connell et al. 2024). Midwives generally rely on fewer medical and surgical interventions, meaning less overall waste, energy usage, and greenhouse gas emissions from avoidable procedures and anesthetics (Altman et al. 2017). Even within a hospital setting, births attended by midwives have up to 40% lower risk of c-section compared to those attended by obstetricians; vaginal births have less than half the environmental impact of c-sections (Cohen et al. 2024; Souter et al. 2019). Looking at midwife-attended homebirths, environmental waste becomes “negligible” (Paxton, Donnellan-Fernandez, & Hastie 2023).

There are also trickle-down benefits of the midwifery model of care. Parents choosing homebirth or attended by a midwife in any setting are more likely to breastfeed/chestfeed7, which is more sustainable than feeding commercial human milk substitutes on every measure: avoiding packaging waste, energy use, and pollution from industrial formula manufacturing and shipping, and minimizing habitat loss, methane emissions, and water usage associated with large-scale dairy farming (Andresen et al. 2022; Wallenborn & Masho 2018)8. In short, an intentional transition to midwife-led, community-based maternity care could improve outcomes while significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions, waste, and energy usage throughout the continuum of care. In this way, abundant healthcare could be abundantly earthcaring, too (Merchant 1995).

Conclusion

This paper is intended primarily as a provocation for further research and discussion on the multifaceted interrelationship between (reproductive) healthcare and the environment. Environmental issues can jeopardize already precarious health and healthcare access for individuals in rural or otherwise underserved areas. Extreme heat, pollution, disease, and disasters all carry special risks for pregnant people and infants. Climate-related disasters such as flooding and fires also threaten both healthcare facilities and the critical transportation infrastructure that people utilize to reach care (e.g., Tarabochia-Gast, Michanowicz, & Bernstein 2022; Johnson et al. 2018). As the need for high-quality reproductive and other health services grows, therefore, issues of access will likely continue to grow alongside. As this paper has noted, healthcare services and transportation can also contribute to anthropogenic climate change and other environmental concerns. Just and sustainable solutions will likely involve not less, but more care for our health, kin, communities, and environment.

Endnotes

1 I use the terms “maternity unit” and “L&D unit” interchangeably throughout to refer to hospital facilities providing birth services, including designated obstetric beds and infant bassinets.

2 Viral disease is illness caused by a virus (e.g., COVID-19). Zoonotic disease is illness or infection that can be transmitted between animals and humans. For example, avian influenza, or bird flu, is a viral zoonotic disease. Vector-borne disease is transmitted to humans and animals through living organisms like mosquitoes, fleas, or ticks (e.g., Lyme disease).

3 Single-use/disposable products include hypodermic needles, syringes, gloves, surgical sponges, bandages, catheters, postpartum pads and cold packs, etc.

4 Emissions estimates for mileage driven by a 2020 Subaru Forester SCV-7 4WD.

5 Again, using the gas tank capacity of a 2020 Subaru Forester.

6 Concept drawn from Birth Center Equity, an organization that funds BIPOC-led community birth centers to “grow abundant community birth infrastructure”.

7 “Chestfeed” is a gender-neutral term for feeding human milk to an infant at the parent’s chest, preferred by some parents.

8 Andresen et al. (2022) found that the environmental impact of four months of exclusive formula feeding was 35-72% higher than four months of exclusive breastfeeding/chestfeeding, depending on the type of impact measured and the lactating parent’s diet.

References

Altman, Molly R., Sean M. Murphy, Cynthia E. Fitzgerald, H. Frank Andersen, and Kenn B. Daratha. 2017. “The Cost of Nurse-Midwifery Care: Use of Interventions, Resources, and Associated Costs in the Hospital Setting.” Women’s Health Issues 27 (4): 434–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.002.

Andresen, Ellen Cecilie, Anne-Grete Roer Hjelkrem, Anne Kjersti Bakken, and Lene Frost Andersen. 2022. “Environmental Impact of Feeding with Infant Formula in Comparison with Breastfeeding.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (11): 6397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116397.

Bekkar, Bruce, Susan Pacheco, Rupa Basu, and Nathaniel DeNicola. 2020. “Association of Air Pollution and Heat Exposure With Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight, and Stillbirth in the US: A Systematic Review.” JAMA Network Open 3 (6): e208243. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8243.

Birth Center Equity. n.d. https://birthcenterequity.org/

Carbon Footprint Calculator. n.d. https://calculator.carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx?tab=4

Cheyney, Melissa J. 2008. “Homebirth as Systems-Challenging Praxis: Knowledge, Power, and Intimacy in the Birthplace.” Qualitative Health Research 18 (2): 254–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307312393.

Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform. 2024. “Addressing the crisis in rural maternity care.” https://chqpr.org/downloads/Rural_Maternity_Care_Crisis.pdf

Cohen, Eva Sayone, Lisanne H. J. A. Kouwenberg, Kate S. Moody, Nicolaas H. Sperna Weiland, Dionne Sofia Kringos, Anne Timmermans, and Wouter J. K. Hehenkamp. 2024. “Environmental Sustainability in Obstetrics and Gynaecology: A Systematic Review.” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 131 (5): 555–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17637.

Colen, Shellee. 1995. “Like a Mother to Them”: Stratified Reproduction and West Indian Childcare Workers in New York. In: F. D. Ginsburg & R. Rapp (Eds.), Conceiving the New World Order: The Global Politics of Reproduction. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Davis-Floyd, Robbie. 2001. “The Technocratic, Humanistic, and Holistic Paradigms of Childbirth.” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 75 Suppl 1 (November):S5–23.

Davis-Floyd, Robbie., Barclay, Lesley, Daviss, Betty-Ann, & Tritten, Jan. 2009. Birth Models that Work. University of California Press.

Dawley, Katy. 2000. “The Campaign to Eliminate the Midwife.” AJN The American Journal of Nursing 100 (10): 50.

DiPietro Mager, Natalie A., Terrell W. Zollinger, Jack E. Turman, Jianjun Zhang, and Brian E. Dixon. 2021. “Routine Healthcare Utilization Among Reproductive-Age Women Residing in a Rural Maternity Care Desert.” Journal of Community Health 46 (1): 108–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00852-6.

Eckelman, Matthew J., Jodi D. Sherman, and Andrea J. MacNeill. 2018. “Life Cycle Environmental Emissions and Health Damages from the Canadian Healthcare System: An Economic-Environmental-Epidemiological Analysis.” PLoS Medicine 15 (7): e1002623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002623.

Ehrenthal, Deborah B., Hsiang-Hui Daphne Kuo, and Russell S. Kirby. 2020. “Infant Mortality in Rural and Nonrural Counties in the United States.” Pediatrics 146 (5): e20200464. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0464.

Environmental Working Group. 2005. “Body Burden: The Pollution in Newborns.” https://www.ewg.org/research/body-burden-pollution-newborns

Gunja, Munira, Evan D. Gumas, Relebohile Masitha, and Laurie C. Zephyrin. 2024. “Insights into the U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis: An International Comparison.” The Commonwealth Institute. https://doi.org/10.26099/cthn-st75.

Gurr, Barbara. 2015. Reproductive Justice: The Politics of Health Care for Native American Women. Rutgers University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6 (1): 159–65. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934.

Harrington, Katharine A., Natalie A. Cameron, Kasen Culler, William A. Grobman, and Sadiya S. Khan. 2023. “Rural-Urban Disparities in Adverse Maternal Outcomes in the United States, 2016-2019.” American Journal of Public Health 113 (2): 224–27. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307134.

Harville, Emily W., Leslie Beitsch, Christopher K. Uejio, Samendra Sherchan, and Maureen Y. Lichtveld. 2021. “Assessing the Effects of Disasters and Their Aftermath on Pregnancy and Infant Outcomes: A Conceptual Model.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 62 (August):102415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102415.

Hung, Peiyin, Katy B. Kozhimannil, Michelle M. Casey, and Ira S. Moscovice. 2016. “Why Are Obstetric Units in Rural Hospitals Closing Their Doors?” Health Services Research 51 (4): 1546–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12441.

Hung, Peiyin, Marion Granger, Nansi Boghossian, Jiani Yu, Sayward Harrison, Jihong Liu, Berry A. Campbell, Bo Cai, Chen Liang, and Xiaoming Li. 2023. “Dual Barriers: Examining Digital Access and Travel Burdens to Hospital Maternity Care Access in the United States, 2020.” The Milbank Quarterly 101 (4): 1327–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12668.

Isenhour, Cindy, Jessica O’Reilly, and Heather Yocum. 2016. “Introduction to Special Theme Section ‘Accounting for Climate Change: Measurement, Management, Morality, and Myth.’” Human Ecology 44: 647–654. doi:10.1007/s10745-016-9866-1

Jang, Caleb J., and Henry C. Lee. 2022. “A Review of Racial Disparities in Infant Mortality in the US.” Children 9 (2): 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020257.

Johnson, Eileen, Jeremy Bell, Daniel Coker, and Elizabeth Hertz. 2018. “A Lifeline and Social Vulnerability Analysis of Sea Level Rise Impacts on Rural Coastal Communities.” Shore and Beach 86 (4): 36–44.

Jolles, Diana, Susan Stapleton, Jennifer Wright, Jill Alliman, Kate Bauer, Carla Townsend, and Lauren Hoehn-Velasco. 2020. “Rural Resilience: The Role of Birth Centers in the United States.” Birth 47 (4): 430–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12516.

Karbeah, J’Mag, Rachel Hardeman, Numi Katz, Dimpho Orionzi, and Katy Backes Kozhimannil. 2022. “From a Place of Love: The Experiences of Birthing in a Black-Owned Culturally-Centered Community Birth Center.” Journal of Health Disparities Research & Practice 15 (2): 47–60.

Klein, Michael, Stuart Johnston, Jan Christilaw, and Elaine Carty. 2002. “Mothers, Babies, and Communities. Centralizing Maternity Care Exposes Mothers and Babies to Complications and Endangers Community Sustainability.” Canadian Family Physician 48 (July):1177–85.

Kozhimannil, Katy B, Peiyin Hung, and Carrie Henning-Smith. 2018. “Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States.” JAMA 319 (12): 1239–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.1830.

Kozhimannil, Katy Backes, Julia D. Interrante, Carrie Henning-Smith, and Lindsay K. Admon. 2019. “Rural-Urban Differences In Severe Maternal Morbidity And Mortality In The US, 2007–15.” Health Affairs 38 (12): 2077–85. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00805.

Kozhimannil, Katy B., Julia D. Interrante, Mariana K. S. Tuttle, and Carrie Henning-Smith. 2020. “Changes in Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Rural US Counties, 2014-2018.” JAMA 324 (2): 197–99. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5662.

Kozhimannil, Katy B., Julia D. Interrante, Lindsay K. Admon, and Bridget L. Basile Ibrahim. 2022. “Rural Hospital Administrators’ Beliefs About Safety, Financial Viability, and Community Need for Offering Obstetric Care.” JAMA Health Forum 3 (3). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0204.

Kuehn, Leeann, and Sabrina McCormick. 2017. “Heat Exposure and Maternal Health in the Face of Climate Change.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (8): 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080853.

Lappé, Martine, Robbin Jeffries Hein, and Hannah Landecker. 2019. “Environmental Politics of Reproduction.” Annual Review of Anthropology 48 (October):133–50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102218-011346.

MacDougall, Christiana, and Krista Johnston. 2022. “Client Experiences of Expertise in Midwifery Care in New Brunswick, Canada.” Midwifery 105 (February):103227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103227.

Maher, Melissa. 2019. “Emergency Preparedness in Obstetrics: Meeting Unexpected Key Challenges.” Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing 33 (3): 238–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000421.

Mercer, Caroline. 2019. “How Health Care Contributes to Climate Change.” CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 191 (14): E403–4. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5722.

Merchant, Carolyn. 1995. “Earthcare: Women and the Environment.” New York: Routledge.

Minion, Sarah C., Elizabeth E. Krans, Maria M. Brooks, Dara D. Mendez, and Catherine L. Haggerty. 2022. “Association of Driving Distance to Maternity Hospitals and Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 140 (5): 812–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004960.

Nelson, Alondra. 2013. Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination. University of Minnesota Press.

Nethery, Elizabeth, Wendy Gordon, Marit L. Bovbjerg, and Melissa Cheyney. 2018. “Rural Community Birth: Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes for Planned Community Births among Rural Women in the United States, 2004-2009.” Birth 45 (2): 120–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12322.

O’Connell, Maeve, Christine Catling, Kian Mintz-Woo, and Caroline Homer. 2024. “Strengthening Midwifery in Response to Global Climate Change to Protect Maternal and Newborn Health.” Women and Birth 37 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2023.10.004.

Paxton, Tani K., Roslyn Donnellan-Fernandez, and Carolyn Hastie. 2023. “An Exploratory Study of Women and Midwives’ Perceptions of Environmental Waste Management – Homebirth as Climate Action.” Midwifery 127 (December):103844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2023.103844.

Rush, Elizabeth. 2023. The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth. Milkweed Editions.

Simpson, Kathleen Rice. 2020. “Ongoing Crisis in Lack of Maternity Services in Rural America.” MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 122 (2): 13. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000605.

Snipe, Margo. 2023. “Black women are losing access to maternity care. This law is partly to blame.” Capital B. https://capitalbnews.org/dangerous-deliveries-maternal-care-deserts/

Sonenberg, Andrea, and Diana J. Mason. 2023. “Maternity Care Deserts in the US.” JAMA Health Forum 4 (1): e225541. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5541.

Souter, Vivienne, Elizabeth Nethery, Mary Lou Kopas, Hannah Wurz, Kristin Sitcov, and Aaron B. Caughey. 2019. “Comparison of Midwifery and Obstetric Care in Low-Risk Hospital Births.” Obstetrics and Gynecology 134 (5): 1056–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003521.

Statz, Michele, and Kaylie Evers. 2020. “Spatial Barriers as Moral Failings: What Rural Distance Can Teach Us about Women’s Health and Medical Mistrust.” Health & Place 64 (July):102396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102396.

Stoneburner A, Lucas R, Fontenot J, Brigance C, Jones E, DeMaria AL. 2024. “Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the US.” (Report No 4). March of Dimes. https://www.marchofdimes.org/ maternity-care-deserts-report

Tarabochia-Gast, A. T., D. R. Michanowicz, and A. S. Bernstein. 2022. “Flood Risk to Hospitals on the United States Atlantic and Gulf Coasts From Hurricanes and Sea Level Rise.” GeoHealth 6 (10): e2022GH000651. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GH000651.

Torjussen, Meghan. 2023. “Expectant mothers face long drives as another rural Maine hospital discontinues its OB services.” WMTW. https://www.wmtw.com/article/expectant-mothers-face-long-drives-as-another-rural-maine-hospital-discontinues-its-ob-services/43471419

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. n.d. “Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator.” https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator#results

Van Wagner, Vicki, Brenda Epoo, Julie Nastapoka, and Evelyn Harney. 2007. “Reclaiming Birth, Health, and Community: Midwifery in the Inuit Villages of Nunavik, Canada.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 52 (4): 384–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.03.025.

Van Wagner, Vicki, Claire Osepchook, Evelyn Harney, Colleen Crosbie, and Mina Tulugak. 2012. “Remote Midwifery in Nunavik, Québec, Canada: Outcomes of Perinatal Care for the Inuulitsivik Health Centre, 2000–2007.” Birth 39 (3): 230–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2012.00552.x.

Wallace, Maeve, Lauren Dyer, Erica Felker-Kantor, Jia Benno, Dovile Vilda, Emily Harville, and Katherine Theall. 2021. “Maternity Care Deserts and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality in Louisiana.” Women’s Health Issues 31 (2): 122–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.09.004.

Wallenborn, Jordyn T., and Saba W. Masho. 2018. “Association between Breastfeeding Duration and Type of Birth Attendant.” Journal of Pregnancy 2018 (March):7198513. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7198513.

World Health Organization. 2023. “Protecting Maternal, Newborn and Child Health from the Impacts of Climate Change: A Call for Action.” https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240085350.

Appendix A: Maine hospitals

| Hospital Name | County | OB Status | Date of Closure |

| Millinocket Regional Hospital | Penobscot | No | Pre-2000 |

| Northern Light Charles A. Dean Hosital | Piscataquis | No | Pre-2000 |

| Northern Light Blue Hill Hospital | Hancock | No | 2009 |

| Penobscot Valley Hospital | Penobscot | No | 2015 |

| Calais Community Hospital | Washington | No | 2017 |

| Bridgton Hospital | Cumberland | No | 2021 |

| St. Mary’s Regional Medical Center | Androscoggin | No | 2022 |

| Northern Maine Medical Center | Aroostook | No | 2023 |

| Rumford Hospital | Oxford | No | 2023 |

| York Hospital | York | No | 2023 |

| Houlton Regional Hospital | Aroostook | No | 2025 |

| Mount Desert Island Hospital | Hancock | No | 2025 |

| Northern Light Inland Hospital | Kennebec | No | 2025 |

| Waldo County General Hospital | Waldo | No | 2025 |

| New England Rehabilitation Hospital | Cumberland | No | N/A |

| Spring Harbor Hospital | Cumberland | No | N/A |

| Northern Light Acadia Hospital | Penobscot | No | N/A |

| St. Joseph Hospital | Penobscot | No | N/A |

| Northern Light Sebasticook Valley Hospital | Somerset | No | N/A |

| Central Maine Medical Center | Androscoggin | Yes | |

| Cary Medical Center | Aroostook | Yes | |

| Northern Light A.R. Gould Hospital | Aroostook | Yes | |

| Maine Medical Center | Cumberland | Yes | |

| Mid Coast Hospital | Cumberland | Yes | |

| Northern Light Mercy Hospital | Cumberland | Yes | |

| Franklin Memorial Hospital | Franklin | Yes | |

| Northern Light Maine Coast Hospital | Hancock | Yes | |

| MaineGeneral Medical Center | Kennebec | Yes | |

| Pen Bay Medical Center | Knox | Yes | |

| LincolnHealth | Lincoln | Yes | |

| Stephens Memorial Hospital | Oxford | Yes | |

| Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center | Penobscot | Yes | |

| Northern Light Mayo Hospital | Piscataquis | Yes | |

| Redington-Fairview General Hospital | Somerset | Yes | |

| Down East Community Hospital | Washington | Yes | |

| Southern Maine Health Care-Biddeford | York | Yes |