Harvest Heritage

By Jordan Ramos

This watercolor painting series illustrates the Maine wild blueberry harvest heritage focusing on small family farms and local and migrant hand-rakers through landscape and harvest scenes. Wabanaki people were the first to manage the fields with a stewardship relationship and the practice of hand-raking. In the early 1900s, hundreds of people and families from Maine, across the U.S. and Canada would flock to the fields to take part in the annual harvest tradition. However, the number of crews have been dwindling and I aim to pay homage to the hardworking communities who keep the cultural heritage of hand-raking alive today. I gathered these scenes through photographing the fields across the Midcoast and Downeast regions of Maine and meeting with small farmers and various migrant hand-raking crews. I was compelled to create this work at a time of large corporations controlling the market making it difficult for smaller farmers to stay afloat in the industry, the rapid conversion to mechanical harvesters amidst labor shortages and profit demands, and the tradition of hand-raking atrophying in community culture. I aim to shed light on the social-ecological relationships of the small farmers and workers who hold up the local food system for Maine wild blueberries. Additionally, I hope these paintings offer new perspectives and spread awareness to consumers and viewers of the interconnection between food, land, and people. I hope this collection invites conversation to viewers on including the heritage of hand-raking into the sustainable practices for field health and conservation of small farms in the wild blueberry industry.

A Shared Generational Harvest

At the top of a sloped field facing Appleton Ridge and a big blue sky, grandkids are raking. This painting depicts Ron Howard, field manager of Brodis Blueberries Farm in Hope, Maine, checking on his grandkids harvesting in late July. The blueberry fields hold shared memories with the many people who have been woven into its harvest season lineage. The fate of those memories held by the land and its people who came to work in the fields is at risk of being lost due to economic challenges, including processor prices that impact land management decisions for small wild blueberry farms. Ron is proud to keep the family harvest tradition going for seven generations on these fields.

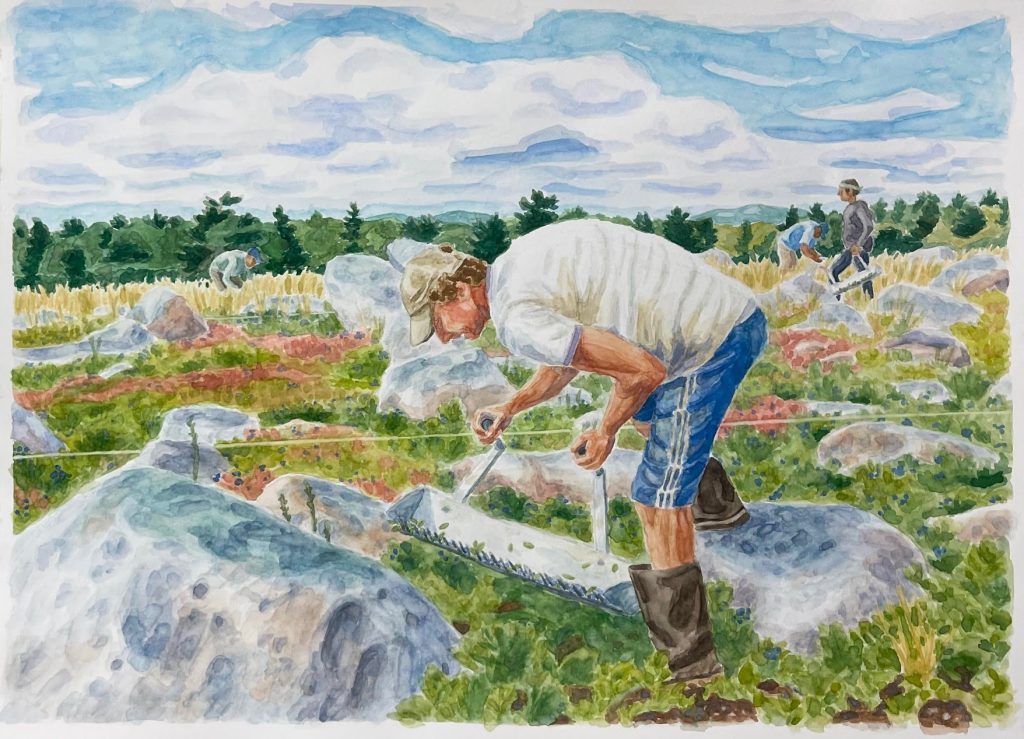

Returning to Work

We meander around the large boulders as we rake up to the end of our strip. Big Rock Field as it is called, is an assortment of boulders that lay blanketed on top of the hummocky topography of the field. This natural landscape was shaped by retreating glaciers that left behind a ridged trail of glacial boulders, creating a moraine. Raking in this field is a hard working job but it is a beautiful place to be in the summer of Maine. I raked on Big Rock with one of the last remaining hand-raking crews of this large company to visit this place. It’s one of the few fields left that retains boulders, an inconvenience to mechanized farming. Hand-rakers get paid piece rate $2.50/box, a price that’s remained the standard for fifty years. This crew voices concern that the tradition of hand-raking being discontinued in the industry is inevitable. The growing arrival of mechanical harvesters on the fields instead of communities of people is coming as the next change in the landscape’s legacy . It won’t be long until they’ll stop returning to Big Rock Field. If the hand-raking crew is terminated and removing the boulders proves to be too expensive, this field will be left for the forest to reclaim. The glacial legacy of this land with wild blueberries to live on is dependent upon people returning to this field to keep managing it.

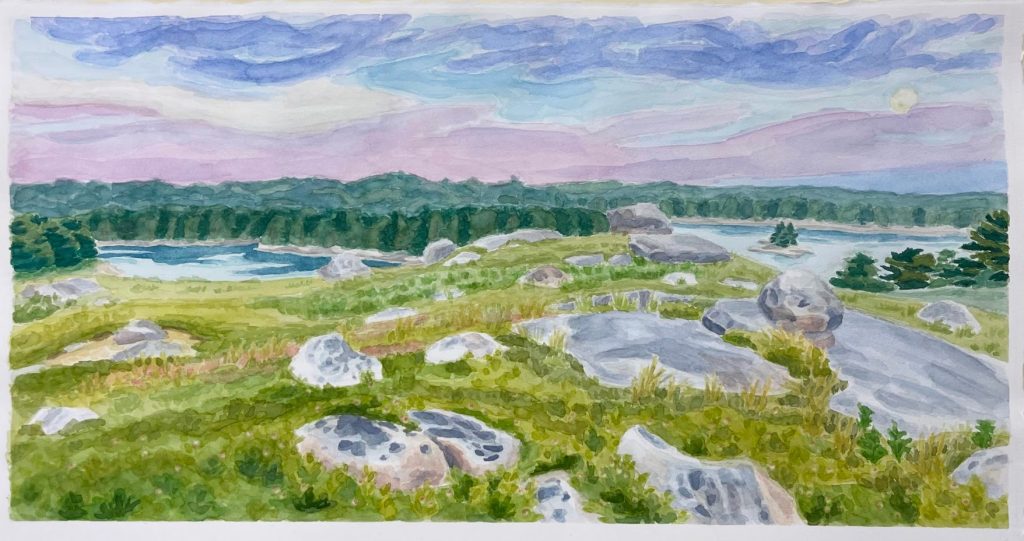

Awaiting the Berries to Turn Blue

In late June, as the sun sets and the moon appears for the night, I look out upon the field, all thickly matted green across the land out to the sea. I step through the plants as they reach just above my ankles, tiptoeing carefully so as not to squish ripening berries. I look down at the tiny green berries hidden amongst the leaves. A few are just starting to swell and turn red to purple on top. Scattered over the entire land, rocks the size of canoes are nestled into the Earth. The patchwork of berries hugs around them for warmth that is absorbed by the sun, claiming their place on this land. This beautiful place exists everywhere in Maine yet is unknown to so many. And yet the reality facing the Maine wild blueberry industry is that so many fields are disappearing. Old farmers are aging or forced to exit the industry because of unprofitable process prices, and the land is being sold or excavated for other purposes. In early fall of 2024, a purchase was made on this land in Blue Hill and Sedgwick, to be developed into house lots.

Following the Harvest

This small crew of guys from Honduras arrive for another day of work in the fields of Harrington, Maine. Based in Florida, this group of men migrate together up the East Coast through the year following the harvest until they reach their last stop in Maine. From Florida they travel to Georgia, and the Carolinas for various fruits, to New Jersey for high bush blueberries, then arrive in Maine by August for the wild low bush blueberries. After quickly trying to harvest as much acreage of land in the short 3-4 week window of ripe berries, they go down to Pennsylvania to pick apples. Then in November they travel back up north to Maine for the Christmas wreath industry, and by the end of the year they return to Florida for a short rest to do it all over again in January. A very tiring job harvesting throughout all the seasons they tell me. Raking alongside them that day I quickly met their tenacious characters, work ethic, and their large hearts as they told me they do this work for their families back home. When I asked for their permission to photograph them while they were raking, they immediately stopped raking in their individual strips and joined next to each other to pose together, like a family photo. Seeing how these men wanted to be seen by the public, speaks to the honorary workers they should be recognized as. As people who come to work in food landscapes, their social well-being is intertwined with the health of the environment in local agricultural communities. These guys answered the call for an extra crew of hard workers to help the family members of this small family farm keep the heritage tradition of hand-raking going in their business. Most of the workers on hand-raking crews for freshly sold wild blueberries in the industry today, are Hispanic migrants.