Harvard, UMaine study challenges assumptions about ‘natural’ lead levels

A new analysis of highly detailed ice core data and historical records shows that human-made lead air pollution has been elevated for approximately the last 2,000 years, except for a four-year period during a devastating pandemic in Europe that halted lead mining.

The findings have significant implications for current public health and environmental policy that, so far, have deemed pre-industrial (before 1800) lead pollution levels to be “natural” or presumably “safe.”

The study by Harvard University and University of Maine researchers shows that due to the Black Death pandemic — the largest plague epidemic to ravage the European continent in the last millennium — an abrupt cessation in mining activity reduced lead air pollution from 1349 to 1353.

This is reflected in ice core data, which researchers say provides evidence that — contrary to common assumptions — the natural level of lead in the air is essentially zero.

“These new data show that human activity has polluted European air almost uninterruptedly for the last ca. 2000 years,” the study’s authors wrote. “Only a devastating collapse in population and economic activity caused by pandemic disease reduced atmospheric pollution to what can now more accurately be termed ‘background’ or natural levels.”

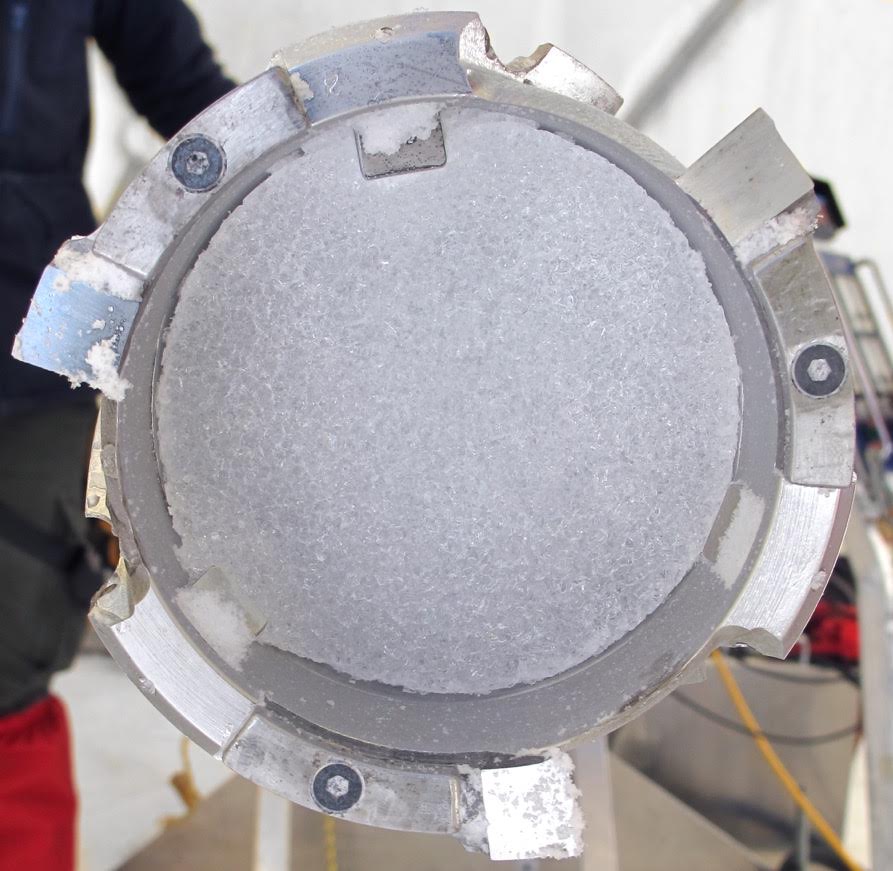

The work, an interdisciplinary collaboration led by historians and climate scientists at Harvard and the University of Maine, matched new high-resolution measurements of lead in an ice core taken from a glacier in the Swiss/Italian Alps with highly detailed historical records, showing that lead mining and smelting activity plummeted to nearly zero during four years of the plague.

“This research represents the convergence of two very different disciplines, history and ice core glaciology, that together provide the perspective needed to understand how a toxic substance like lead has varied in the atmosphere and, more importantly, to understand that the true natural level is in fact very close to zero,” says Paul Mayewski, director of the UMaine Climate Change Institute and co-author of the study.

The project, which also involved collaborators from Heidelberg University and the University of Nottingham, shows that lead levels declined precipitously in a section of the ice core corresponding to that four-year window of time, a decline unparalleled in the last 2,000 years of European history, says Alexander More, a postdoctoral fellow in Harvard’s Department of History and at the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

More was first author of the paper on the research published in GeoHealth, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

The authors challenge assumptions that widespread environmental pollution began with the Industrial Revolution (after ca. 1800), where some scholars recently have placed the beginning of a new era dubbed the “Anthropocene.”

Such studies, and policies based on them, maintain that lead air pollution in the pre-industrial world represented natural or background levels.

This research, however, shows that lead from mining and smelting — which has occurred for thousands of years — was detectable well before the Industrial Revolution.

Only when such activities were essentially halted by the plague pandemic did lead pollution in the air decline to natural levels.

“When we saw the extent of the decline in lead levels, and only saw it once, during the years of the pandemic, we were intrigued,” says More, who also is a postdoctoral fellow with the Climate Change Institute.

“In different parts of Europe, the Black Death wiped out as much as half of the population. It radically changed society in multiple ways. In terms of the labor force, the mining of lead essentially stopped in major areas of production. You see this reflected in the ice core in a large drop in atmospheric lead levels, and you see it in historical records for an extended period of time.”

Mayewski adds, “Sadly, if you kill off half the population of Europe, everything stops. It’s tremendously important because it shows the impact of an abrupt disease event.”

The research, backed by the Arcadia Fund of London, the W. M. Keck Foundation and the National Science Foundation, was enabled, in part, by the development of a more precise instrument to analyze ultra-thin layers of ice contained in the core.

Designed and operated at the Climate Change Institute, the W. M. Keck Laser Ice Facility can analyze ice layers thin enough to coincide with sub-annual time periods, even in highly compressed ice.

Study co-authors Nicole Spaulding, Pascal Bohleber, Michael J. Handley, Elena V. Korotkikh, Andrei Kurbatov, Sharon Sneed and Mayewski at UMaine produced and analyzed millions of datapoints from the ice core, an effort that ushers in a new era in climate research.

“Using the ultra-high resolution ice core sampling offered through our W.M. Keck Laser Ice Facility, we expect to be able to offer new insights, previously unattainable with lower-resolution sampling, into the links between climate change and the course of civilization,” says Mayewski.

The findings are troublesome, he says. Before this project, Mayewski says the natural level of lead in the atmosphere had not been documented.

More says the researchers chose to examine lead in the ice core because it’s a dangerous pollutant and because it serves as a proxy for economic activity, ramping up when the economy is growing and tailing off when it declines.

“Lead is one of the most dangerous pollutants in the air, and one we’ve mined for a very, very long time; it was ubiquitous in the pre-industrial world, widely used in construction, pipes, currency and everyday utensils,” More says.

“It is one of the first things we studied because of its role as an economic proxy and its impact on human health.”

The study benefited from the archaeological and historical expertise of Michael McCormick, chairman of the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard, and Christopher Loveluck of the University of Nottingham, a former visiting professor at Harvard.

McCormick, Loveluck, More and others analyzed an extensive collection of detailed written records that contain information about economic activity, epidemics, climate events and food shortages in Europe.

“It’s crucial to acknowledge the contribution of our wonderful undergraduate and graduate students, who worked hard to help the whole team build the critical geodatabases of historical climate records that are playing such a role in our ongoing analyses,” says McCormick.

The research highlighted other, lesser drops in lead accumulation in the ice core: one in 1460, which the authors show also may have been due to an epidemic-related downturn; a second during another economic slowdown in 1885 and, most recently, beginning in the 1970s, when abatement policies phased out leaded gasoline and other sources of anthropogenic air pollution.

Philip Landrigan, dean of global health for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, who has studied the epidemiology of lead poisoning in children, says the work highlights today’s good news/bad news situation of lead in the environment.

While widespread contamination due to leaded gasoline, lead paint, lead solder and other common modern-era applications has been curbed by government regulation, the recent crisis of tainted water in Flint, Michigan shows that lead continues to poison children in America and elsewhere.

One recent estimate, says Landrigan, who did not participate in the research project, holds that some 535,000 American children younger than 6 years old have elevated blood lead levels.

The new research, which Landrigan calls “meticulously well-done,” also reinforces the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recent statements that no level of lead can be considered safe in children.

“Lead is toxic to the brain at extremely low levels,” says Landrigan, who, while working with the CDC in the 1970s, investigated lead poisoning in children near a Texas lead smelting plant. “It’s clear that lead has lasting effects on children’s lives.”

The research follows similarly collaborative work presented a year ago that also coupled ice-core data with historical records to help explain the Black Death’s high death toll.

That work showed that a famine that struck Europe in the years prior to the plague’s arrival was likely much longer and broader geographically than previously understood. Caused by unusually cool, wet weather, it likely led to multi-year food shortages that could have weakened the population before the plague ravaged the continent.

The same ice core — taken by scientists from Heidelberg University, the University of Bern and the CCI — from the Colle Gnifetti glacier high in the Alps, was used in both projects.

With the precision afforded by the CCI’s next-generation laser facility, the ice core still holds much more data that, when combined with historical sources and established methodologies, can lead to new discoveries in the fields of climate science, the history of human and planetary health, and economic history.

“The amount of data that has come out of this ice core is unprecedented,” More says. “This trans-disciplinary approach is an exciting new way to do research and expand our understanding of known events and sources in a new dimension.”

Contact: Alexander More, 617.417.5608; Beth Staples, 207.581.3777