Expanding the dialogue: Climate science in the classroom

On Friday, June 26, as various school systems came to the end of their academic calendars, 17 Maine high school and middle school teachers and 12 science researchers gathered around small tables at the University of Maine, all with the same topic in mind.

Climate change.

The group participated in a climate science teacher workshop led by Amy Kireta and Bjorn Grigholm, Ph.D. students with the Climate Change Institute (CCI) at UMaine. The workshop offered resources, activities and presentations to empower teachers to use a variety of tactics to discuss climate change in their classrooms.

Kireta and Grigholm are participants in the Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) — the National Science Foundation’s flagship interdisciplinary training program. The purpose of UMaine’s IGERT is to tackle the issue of adaptation to abrupt climate change (A2C2) and to involve perspectives from a wide range of disciplines.

Part of the A2C2 program is to form teams or subgroups from different disciplines to come up with a collaborative immersion project — a project related to affecting climate change policy that may be different than primary research interests.

Kireta and Grigholm paired up for the project because they were both interested in the educational outreach aspect of research.

“A lot of times when you’re sitting in a freezer scraping ice you are wondering what you are doing for the greater world,” said Grigholm, who expects to defend his dissertation in November. “And I mean, I’m going to write a scientific paper but maybe only a handful of scientist will end up reading it. I wanted to be doing more.”

“We were really interested in education and outreach and the public misperception when it comes to abrupt climate change. We really wanted to address that,” said Kireta.

Before the workshop, the team sent out a teacher survey to assess how climate change was being addressed in Maine’s public school systems. The survey focused on teaching practices, knowledge, motivation, attitudes, barriers and resources used in topics related to climate science.

The targeted survey group was middle and high school science teachers, but they received nearly 400 responses from teachers across Maine in a variety of disciplines.

One of the major findings was the interdisciplinary nature of climate change across subjects. Maine teachers not only discuss climate change in science class, but across many different subjects, including the social sciences.

The workshop, which focused on incorporating climate change educational activities in the classroom, featured presentations from Paul Mayewski, CCI director, and Kirk Maasch, professor in the Climate Change Institute and the School of Earth and Climate Sciences at UMaine.

“The teachers really enjoyed the presentations because they were given by two world experts on these subjects,” said Kireta. “The two professors spoke about the current climate, climate variability and introduced the concept of abrupt climate change to describe, clarify, and help explain the relevancy of these issues to our everyday lives.”

“Often times when people think about climate change, it’s this linear thing occurring at the same rate,” said Grigholm. “But, he (Mayewski) emphasized that these things could happen at any point and that there are certain tipping points for these events. We have to be, as a society, planning for this.”

Both professors made their presentations available to the teachers so that they could use them in the future as resources in the classroom.

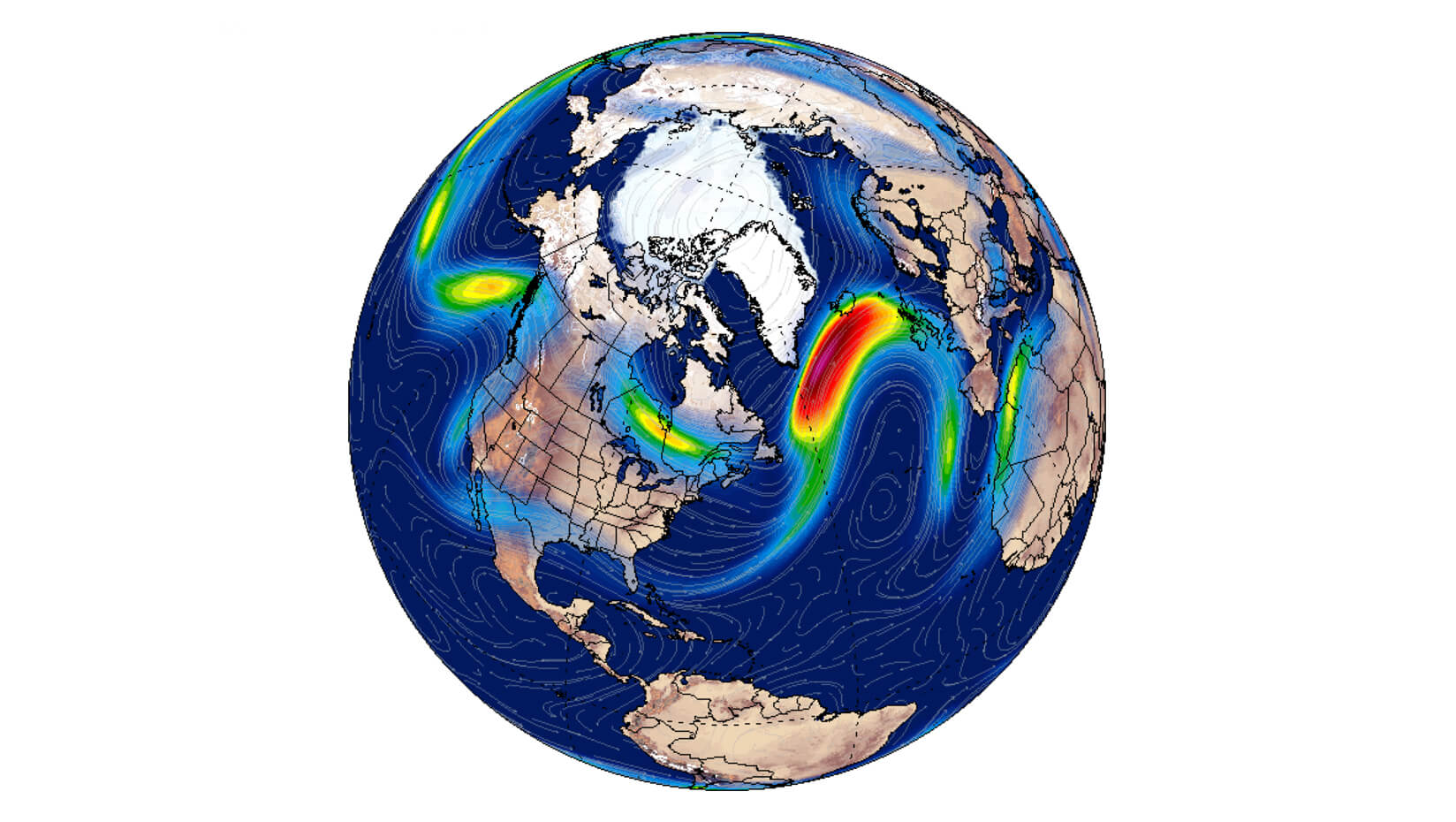

The researchers also introduced the Climate Reanalyzer, an online, intuitive platform for visualizing a variety of weather and climate datasets and models that can also be used as an interactive teaching module.

One of the goals for using the Climate Reanalyzer, developed by Sean Birkel at the Climate Change Institute, was to explain the difference between long-term climate change and climate variability. “The climate changes from year to year, but in order to understand climate change you have to look a long-term trends,” said Grigholm.

Representatives from the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance (MMSA) and the Maine Energy Education Program (MEEP) also attended the workshop to discuss the connection between climate change and human action, as well as how to get students engaged in the topic and how teachers can incorporate the Climate Reanalyzer into their lesson plans.

“There are some scary uncertainties out there about what is going to happen, but there are a lot of interesting things going on in terms of adaptation projects and opportunities, so it’s important to highlight those so things don’t feel so overwhelming, especially at such a young age,” said Grigholm.

After the workshop, the researchers asked the teachers to participate in a post-workshop survey. The researchers said they were overwhelmed with the positive responses.

“I didn’t know what to expect,” said Grigholm. “Working directly in a workshop was relatively new for me. You don’t know if you are throwing too much at them, or too little. But just hearing the positive responses from the teachers and how grateful they were, that was really great to hear.”

“It was a lot of work, but it was extremely rewarding,” said Kireta. “It is wonderful to know that there are people just as passionate about climate change as we are, and they are working very hard every day to understand and educate the challenges we are facing.”

The workshop also introduced other resources available on the Climate Change Institute website, such as the Maine’s Climate Future — an assessment that builds off a report released in 2009 that focuses on future trends in light of a changing climate specific to the state.

“I think through the IGERT program, we are starting to appreciate the importance of coming together to talk about the challenges of climate change,” said Kireta. “Being aware of these problems is an adaptation solution in itself. By forming groups who are concerned about the risks and who want to learn from each other, we are building social networks that can identify and work together towards solutions, instead of just responding to disasters. It can really go a long way in making people feel empowered.”

Grigholm’s dissertation research uses ice-core samples to investigate climate and environmental conditions in central Asia the last 500 to 1,000 years. He also participates in a variety of educational outreach programs and interdisciplinary collaboration projects.

“When I decided I was going back to school, I wanted to do science that was relevant and had outreach and education components,” said Kireta, who studies lake ecology and lake sediments using diatom algae as indicators of climate change.

“I think climate education needs to be a part of the basic education of a citizen,” said Grigholm. “Not just understanding Earth science, but looking at it as the bigger picture, spanning all disciplines.”

Contact: Amanda Clark, 207.581.3721