Penobscot women and the tribal land tenure system in 19th-century Maine

In the 19th century, Penobscot grandmothers approved marriages, adjusted family disputes, sanctioned divorces and carried wampum.

The tribe’s grandmothers’ council (nohkəməssizak mawebohwak, or the modern spelling, nohkomess potawasin) could veto a declaration of war by the chief and tribal council.

Penobscot women had powerful and wide-ranging roles in their society, and their importance was embedded in the unique land system Maine state officials created in 1835, says Micah Pawling, associate professor of history and Native American Programs at the University of Maine.

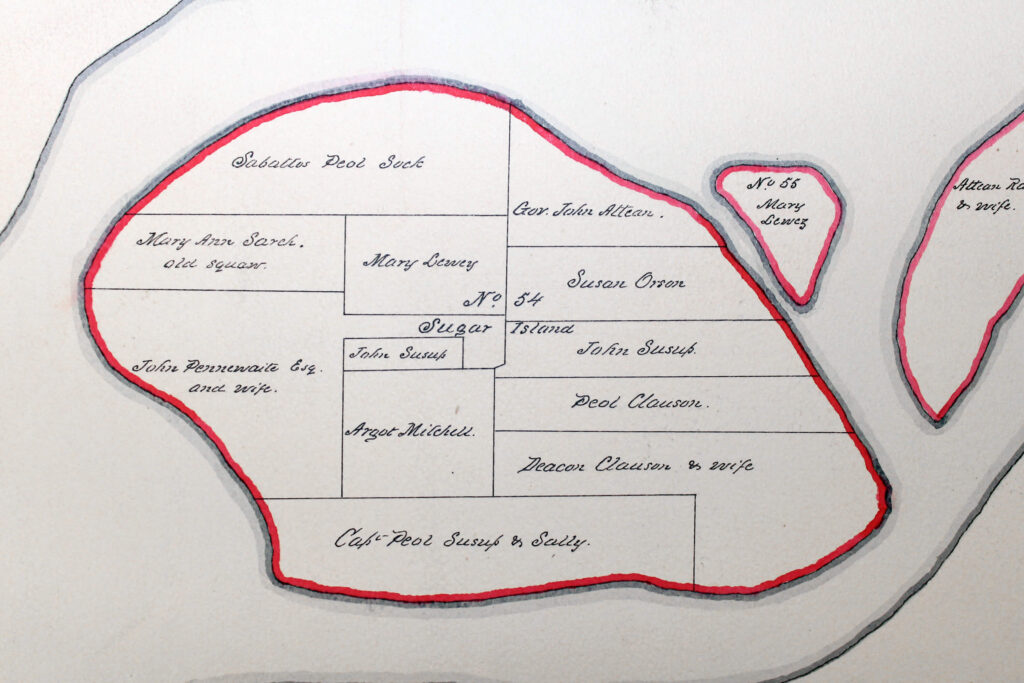

That year, surveyor Zebulon Bradley assigned lots to tribal members on the 146 reservation islands in the Penobscot River.

He did so after Penobscot Joseph Sockabasin — who started farming on reservation land to escape the “abyss of poverty and wretchedness” caused by the encroachment of European Americans — sought a deed from the state permitting him to pass on his farm land to his family.

Under this new land tenure system, all Penobscots 21 years and older could apply for a land lot on a reservation island. Women, like men, owned lots as individuals and as spouses.

Married Penobscot women owning land on the river islands represented an indigenous value, and preceded by nearly a decade Maine’s 1844 Property Law that granted married women the right to own property, says Pawling.

This method for Penobscots to possess specific lots, coupled with the recognition of communal reservation islands, powerfully reinforced tribal land ownership and hindered further dispossession, he says.

Pawling describes the unique dual land system, including the recognized right of married Penobscot women to own property, in ”A ‘Labyrinth of Uncertainties’; Penobscot River Islands, Land Assignments, and Indigenous Women Proprietors in Nineteenth-Century Maine.”

The American Indian Quarterly published the article.

Darren Ranco, UMaine associate professor of anthropology and chair of Native American Programs, says Pawling’s research highlights important elements of the roles women have in Penobscot and in other Wabanaki Tribal Nations in Maine and the Maritimes.

“The strength of these powerful roles is revealed by the fact that the state of Maine had to recognize Penobscot women (ahead of White women) as landowners during some of the darkest times of our history as Penobscot people in the 19th century,” he says.

“While these roles may be surprising in the context of American women’s rights at the time, matrilineal cultural preferences in Wabanaki societies meant women had far more power than their non-Native counterparts.”

Sherri Mitchell (Weh’na Ha’mu Kwasset), founding director of the Land Peace Foundation, says Pawling’s article “emphasizes a number of critical factors regarding the matrilineal history of Wabanaki Nations and the vital role that women played in maintaining security for the family and community.

“It also highlights the conflicts that erupted as a result of colonization. …The lasting impacts of those conflicts still plague us today,” says Mitchell. “Recognizing the disruption of matrilineal traditions and the harmful influence of colonial structures informs us of the importance of moving back into alignment with our traditional ways of being, so that we can heal our families and communities. The women are at the heart of that movement.”

Pawling says Penobscots’ own land tenure system was reminiscent of Penobscot family hunting territories. European Americans, though, colonized Penobscot homeland and violated indigenous values about family hunting territories. Sockabasin conveyed in his petition that “new obstructions are every year erected upon the river and the forest [is] daily wasting away.”

By the 19th century, European Americans had constructed sawmills, organized log drives, erected boom islands, and built dams to harness water power, which harmed the river’s water quality, impeded canoe travel and depleted aquatic life.

And in 1833, a fraudulent sale of four upper Indian Townships further reduced the Penobscot land base to the river islands.

When the state instituted its land system, some Penobscot women experimented with deeds and asserted their rights to island lots, says Pawling.

Other Penobscots, though, continued to maintain their own system. They had “wickhegans” (or wikhikon/wikhikonol (plural), meaning any written material that can be read) — including wampum belts, birchbark maps, and in this specific case, old deeds — that already supported their claims to specific lots.

The state-assigned parcels, which today are called assignments, were the result of colonialism, says Pawling. To some degree, though, they provided Penobscots access to their ancestral waters that are central to their livelihood and identity on the river.

Today, tribal leaders consult with lot owners, who have final say about land decisions. This consultation protects Penobscots from further dispossession, he says.

In a tribal publication, a Penobscot citizen wrote that the protected reservation islands “provide a place for the people to return to the earth and enter into the silence of the river. … Preservation of this invaluable asset will perpetuate the natural and cultural qualities of The Penobscot Indian Nation.”

Pawling learned of the origins of this dual land system from his work with the tribe, Penobscot petitions at the Maine State Archives in Augusta, and Penobscot Indian deeds in the Penobscot County Registry of Deeds.

It’s gratifying, he says, to share the research findings. “Readers will hopefully appreciate the Penobscots’ continued presence in their homeland, along with some of the specific challenges they confronted and their attempts to shape its outcomes.”

Contact: Beth Staples, 207.581.3777, beth.staples@maine.edu