Record early-October warmth across the Arctic

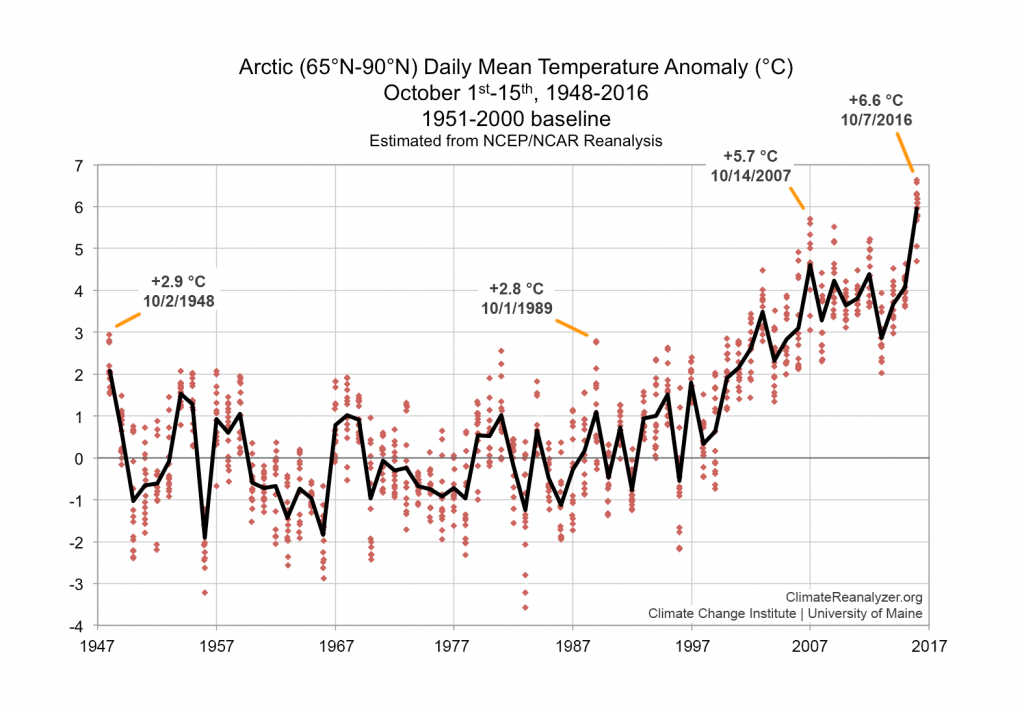

The first half of October 2016 was likely the warmest across the Arctic for this time of year since at least 1948, says Maine’s state climatologist.

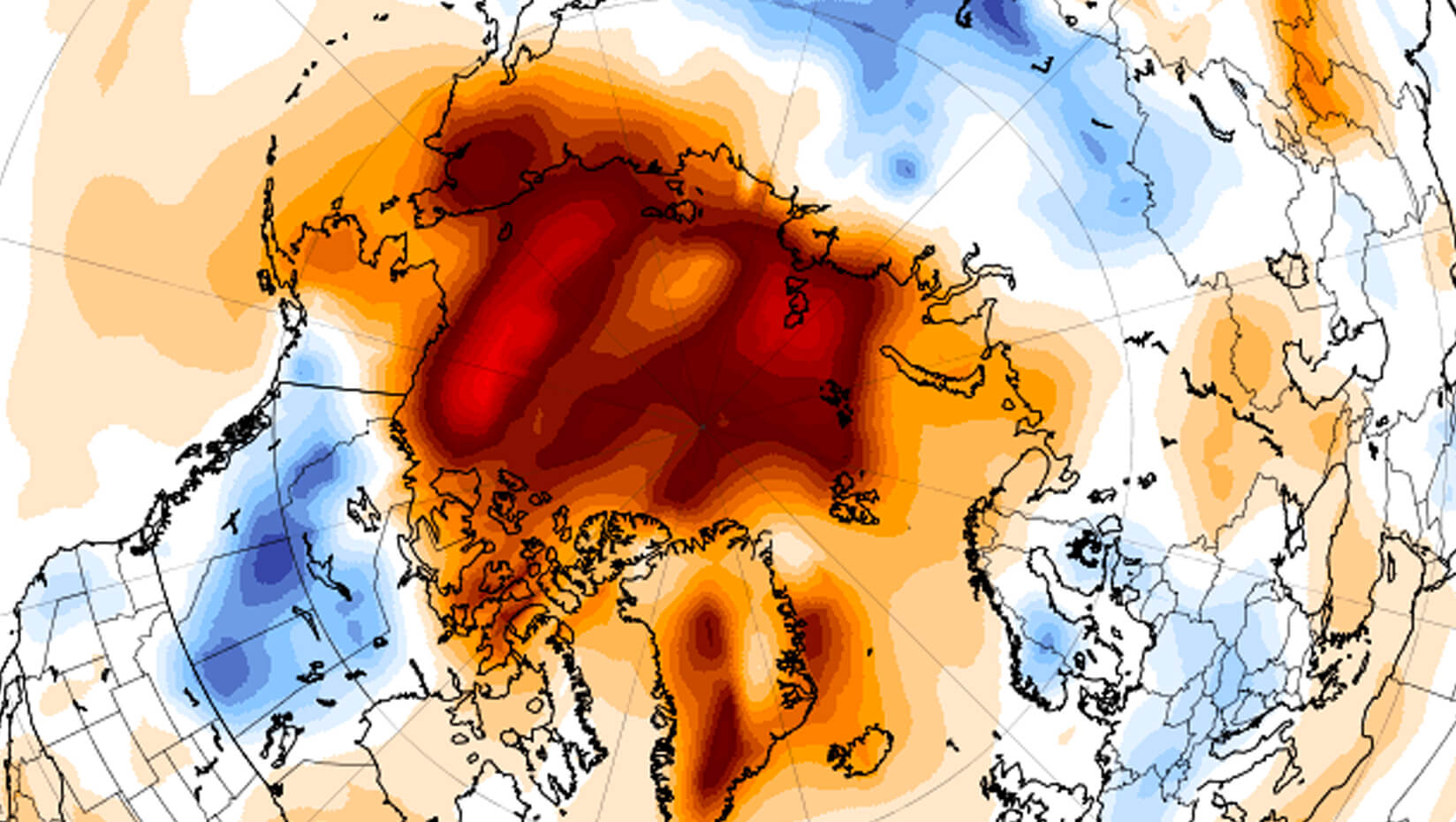

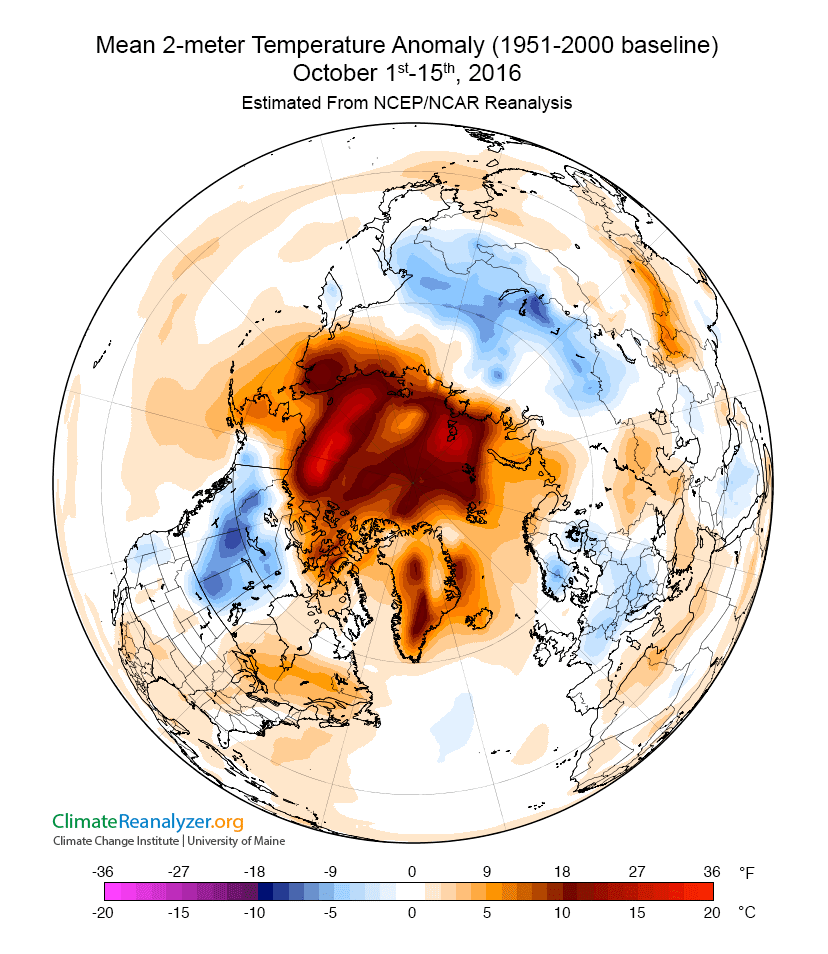

In the Arctic — 65–90 degrees north latitude — on Oct. 7, 2016, the mean daily temperature averaged a balmy minus 3.5 C (25.7 F), a value that’s 6.6 C above the 1951–2000 historical mean, says Sean Birkel, who also is a research assistant professor at the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine.

This temperature departure from average, or anomaly, exceeds the previous record daily temperature anomaly of 5.7 C set Oct. 14, 2007.

For comparison, prior to 2000, the highest Arctic-wide temperature anomaly for early October prior was 2.9 C, which was attained Oct. 2, 1948.

These temperature anomaly estimates are based on output from a widely used climate reanalysis model developed by the National Center for Environmental Prediction and National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Reanalysis models assimilate station, weather balloon and satellite data to reconstruct the state of the atmosphere across the globe or a region at regular time intervals.

This is particularly valuable for estimating conditions across areas of the Earth for which few observations are available, including across the Arctic Basin, says Birkel.

Record warmth in the Arctic has increasingly become the norm, he says, as feedbacks between declining snow/ice cover, the atmosphere, and the ocean have been observed.

Unusual warmth this time of year is diagnostic of changing season length: Arctic summers are warmer and longer than they used to be, while winters are warmer and shorter.

In turn, this year’s September minimum sea-ice extent tied that of 2007 as second-lowest in the satellite era. The record minimum was attained in 2012, says Birkel.

The current October warmth results in large part from open water over broad areas historically covered by ice this time of year, he says.

A steep decline of sea-ice cover has been linked to changing weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere, including in Maine and New England, he says.

Rapid warming of the Arctic has reduced the mean temperature difference between the equator and pole, which some researchers suggest has slowed the westerly jet stream, says Birkel.

This process leads to greater likelihood for the development of atmospheric blocking patterns that can cause heat waves, cold waves and extreme rainfall events in the middle latitudes, he says.

On Oct. 3, Birkel and CCI director Paul Mayewski were part of a UMaine contingent attending the Maine-Arctic Forum in Portland, Maine, which focused on the Arctic’s changing climate and resulting economic opportunities and geopolitical concerns.

To learn more about local and worldwide weather and climate, visit the Climate Reanalyzer.

Birkel maintains the platform with support from the CCI, UMaine and the National Science Foundation. Also, a general overview of Maine’s climate is in the 2009 and 2015 Maine’s Climate Future documents produced by the UMaine Sea Grant and Climate Change Institute.

Contact: Beth Staples, 207.581.3777