Maine Schools in Focus: Evidence-Based Practices for Technology-Enhanced Learning

Sara Flanagan, Assistant Professor of Special Education

Sarah Howorth, Assistant Professor of Special Education

Deborah Rooks-Ellis, Assistant Professor of Special Education

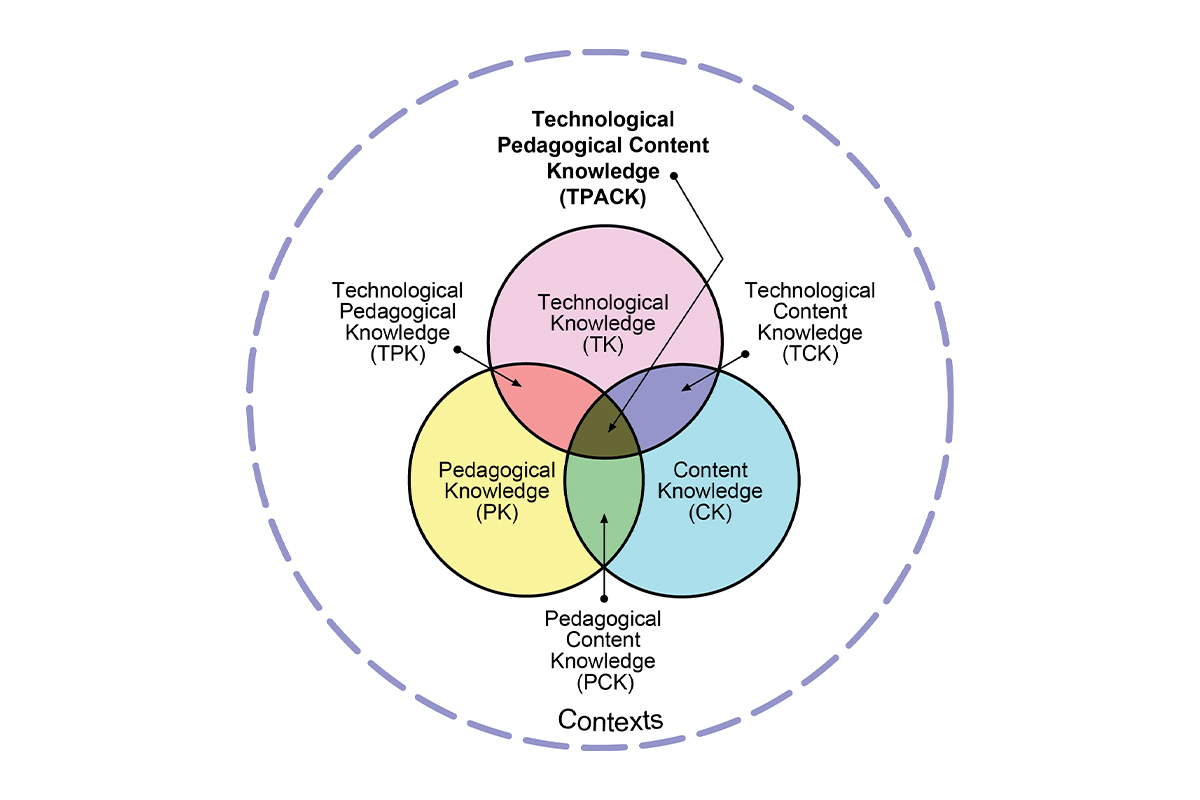

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted an already urgent need for educators to develop their technological and pedagogical content knowledge—what some in education refer to as TPACK—in order to be effective practitioners in technology-enhanced learning environments.

But what are the evidence-based practices for delivering instruction in asynchronous or synchronous remote or online settings? Current technology-based distance education systems have only been studied for about the last decade at the K-12 level, a very short time in which to build a body of literature (Bebell & O’Dwyer, 2010). A variety of assistive and instructional technologies have been designed to provide students greater access to curriculum and to increase their potential for school success. The quality of technology—what and how it is used—is a more significant factor than the quantity of technology available for learning and teaching (Lei, 2010). The 2018 Project Tomorrow report indicates that teachers’ use of digital tools in the classroom helps students develop the types of workplace and college-ready skills they need to be successful in the future, and the effective use of those tools is enabling more equitable learning experiences at school (Evans, 2018).

The TPACK framework emphasizes the purposeful use of technology that is matched to the intersection of pedagogy, technological knowledge and content knowledge. Essentially, instead of starting instructional planning with a specific technology in mind, technology is added to instruction if it meets at the intersection of TPACK. The learning objective, rather than the technology tool is the first consideration. The idea is to understand how to use technology to teach concepts in a way that expands and enhances student engagement and learning.

For example, teachers deliver pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) using Google Classroom and recognize that the content will engage students if they create interactive learning opportunities, such as videos, breakout groups, online quizzes and discussions. These expanded learning opportunities represent teachers’ understanding of technological content knowledge (TCK).

Supporting Accessibility for All Students

Technology also provides a tool for implementing the principles of universal design for learning (UDL) in today’s diverse classrooms (Lock & Kingsley, 2007; Okolo & Diedrich, 2014; Rose & Dalton, 2009). According to UDL proponents, no single curricula, method, material or instructional strategy will work for all students. They argue the use of UDL increases access, reduces barriers and assists students with a variety of needs. In terms of remote learning, common barriers students may face include time management and finding the needed information in an online platform. To reduce such barriers, teachers may consider having a consistent layout for all online information; a checklist for objectives, so students to know exactly what they are trying to accomplish; and clearly labeled assignments (e.g., using the label “Reading Comprehension Review Assignment” to indicate that the content is an assignment for the specific topic). Information can be presented in a variety of ways, such as text, video, audio and/or images. Educators should think about selecting technology that works best for students’ different learning needs and the instructional objectives.

Barriers to Technology Access at Home

Another consideration for educators and policymakers in selecting technology to support instructional goals is the continued barrier of the “digital divide” that creates inequities in access to internet service and hardware in different communities. A recent national report from the U.S. Department of Education (Gray, Lewis & Chapman, 2020) provides information about technology used for homework assignments in grades 3-12. The report, which covered the 2018-19 school year, indicates that while computers and internet service might exist in students’ homes, the availability of computers for homework and the reliability of internet access varies considerably. Only about a third (35 percent) of teachers estimated that their students’ home computers were “very available” for school assignments. Furthermore, just 29 percent of teachers thought it “very likely” that their students’ home computers had reliable internet access. Finally, only 19 percent of teachers reported that they “often” assign technology-based homework and an additional 28 percent reported doing so “sometimes.” If two-thirds of families do not have a computer available for schoolwork, how can schools ensure equitable access to public education?

Maine may be ahead of the curve regarding this concern and poised as a leader for our nation’s schools due to the Maine Learning Technology Initiative (MLTI), which made laptops and other devices widely available in middle school and other grades beginning in 2002. The Maine Department of Education (MDOE) provided professional development sessions on using technology as a tool to deliver remote instruction during the 2019-20 school year’s spring semester. However, for many students with the most severe learning challenges, many of the interventions they need such as occupational therapy, physical therapy, intensive behavior therapy and vocational training cannot be adequately delivered in a remote format. In addition, in many parts of Maine—particularly rural areas—reliable broadband internet service is not available for all homes (ConnectMaine Authority, 2020).

As Maine schools prepare for the coming school year, and the uncertainty about how instruction will be delivered to students, many resources are available both in the state and nationally to support conversations, professional development efforts and decision-making about how and when to use technology in thoughtful ways that effectively support students’ diverse learning needs, as well as teachers’ instructional goals. We provide links to some of these resources below.

Resources

We are in uncharted territory when it comes to ensuring equity and digital access to a free and appropriate education during these challenging times, and guidance provided by the Maine Department of Education Office of Special Services and the federal Office of Special Education Programs should be consulted. MDOE also offers resources for teachers and families to support student engagement and learning during the covid-19 pandemic. Other reputable resources for remote learning and technology instructional tools include:

- Resources for Teaching Remotely from the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC): CEC is the leading organization for supporting individuals with disabilities. CEC compiled a list of resources for different grade levels, content areas, and other topics (e.g., social-emotional learning, working with paraprofessionals remotely). While this a special education website, the information included is applicable for any student with or without a disability.

- Resources for Supporting Families Remotely Using Tele-Intervention: The Division for Early Childhood, a division of CEC, promotes policies and advances evidence-based practices that support families and enhance optimal development for young children (0-8).

- Educating All Learners: Special Education: This comprehensive website has a list of resources that have been evaluated by educational experts and is endorsed by a number of education organizations, including CEC, the National Center for Learning Disabilities, and the International Society for Technology in Education.

- Technology in Action Videos: This link includes a variety of videos on technology in education, including creating accessible materials and assistive technology, from Innovations in Special Education Technology (ISET). ISET is a division of the CEC focused on innovative technology-based solutions for today’s needs.

- Educating Students with Disabilities in Remote Settings: This article provides useful, practical tips and suggestions for online, remote learning for students with disabilities by applying UDL and explicit instruction.

- Remote Learning Resources from CAST: CAST, an organization dedicated to UDL, developed a list of resources related to remote learning. Resources include articles on supporting executive function, creating accessible documents, and developing instruction.

- International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE): https://www.iste.org/

References

Bebell, D. and O’Dwyer, L. (2010). Educational outcomes and research from 1:1 computing settings. The Journal of Technology, Learning and Assessment, 9(1). Retrieved from https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/jtla/article/view/1606

ConnectMaine Authority. (2020). State of Maine Broadband Action Plan. Maine Department of Economic and Community Development. Retrieved from: https://www.maine.gov/connectme/sites/maine.gov.connectme/files/inline-files/State%20of%20Maine%20-%20Statewide%20Broadband%20Action%20Plan%202020_1.pdf

Evans, J.A. (2018). The educational equity imperative: Leveraging technology to empower learning for all. Project Tomorrow. Retrieved from: https://tomorrow.org/speakup/speakup2017-educational-equity-imperative-september2018.html

Gray, L., and Lewis, L. (2020). Teachers’ use of technology for school and homework assignments: 2018-19. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020048

Lei, J. (2010). Quantity versus quality: A new approach to examine the relationship between technology use and student outcomes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(3), 455-472

Lock, R.H. & Kingsley, K.V. (2007). Empower diverse learners with educational technology and digital media. Intervention in School and Clinic, 43(1), 52-56

Okolo, C. M., & Diedrich, J. (2014). Twenty-five years later: How is technology used in the education of students with disabilities? Results of a statewide study. Journal of Special Education Technology, 29(1), 1-20

Rose, D. & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain, and Education, 3(2), 74-83

Any opinions, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in the Maine Schools in Focus briefs are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect institutional positions or views of the College of Education and Human Development or the University of Maine.