Learning, Big Data and Responding to Political Climate Change

I was excited last week when Sheridan told me about data.world. It is a social network for people who work with open datasets. This independent site and service encourages and supports individuals and groups who work with datasets to collaborate and share.

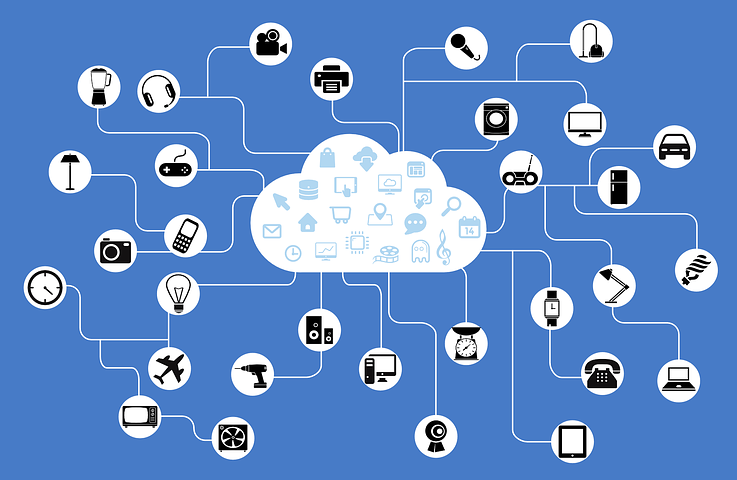

Today we live, learn, and teach in a moment increasingly characterized by big, dynamic datasets as well as the internet-connected devices that gather the data. But almost always, we understand the data in a context. For instance, when NASA and NOAA reported that 2016 was the hottest year on record, they did so in the context of more than a century’s worth of data collected from locations around the country and the world. When UMaine faculty and students study aquaculture, they do so, in part, in the context of weather and other environmental data.

I have supported university faculty and students in courses that use large datasets in the US as well as abroad in countries such as China and the UAE. This experience has made me sensitive to the continued availability of data important to understanding our world, especially when governments collect and manage that data.

Only a couple of years ago Florida, under Governor Scott, would not allow the state’s Department of Environmental Protection nor any of its employees to use the terms and phrases “global warming,” “climate change,” or “sea-level rise.” On the other hand, more than just prohibiting labels, when he was Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper censored government scientists for nine years and directed the destruction of data.

In January 2017 groups of university academics and librarians in the US and Canada worked to download and preserve climate data from the US EPA, NOAA, and other agencies in fear that the information would be removed and destroyed by the US government.

On January 19th, inauguration day, the new US presidential administration removed references to climate change from the White House website. The following week the new administration forbade EPA, HHS (including the CDC) and USDA employees from sharing research and otherwise communicating with the public. While employees of these and other agencies started underground postings on social media platforms, this is not the same as collecting and sharing big datasets.

When we think back to some of the first systematic collections of data, we will recall the importance of sustained individual efforts on campuses around the country as well as the passing of responsibility from generation to generation such as the Ives Weather Station at Amherst College.

Is it now our time?