Graduate Student Symposium Illuminates Marine Science Advancements

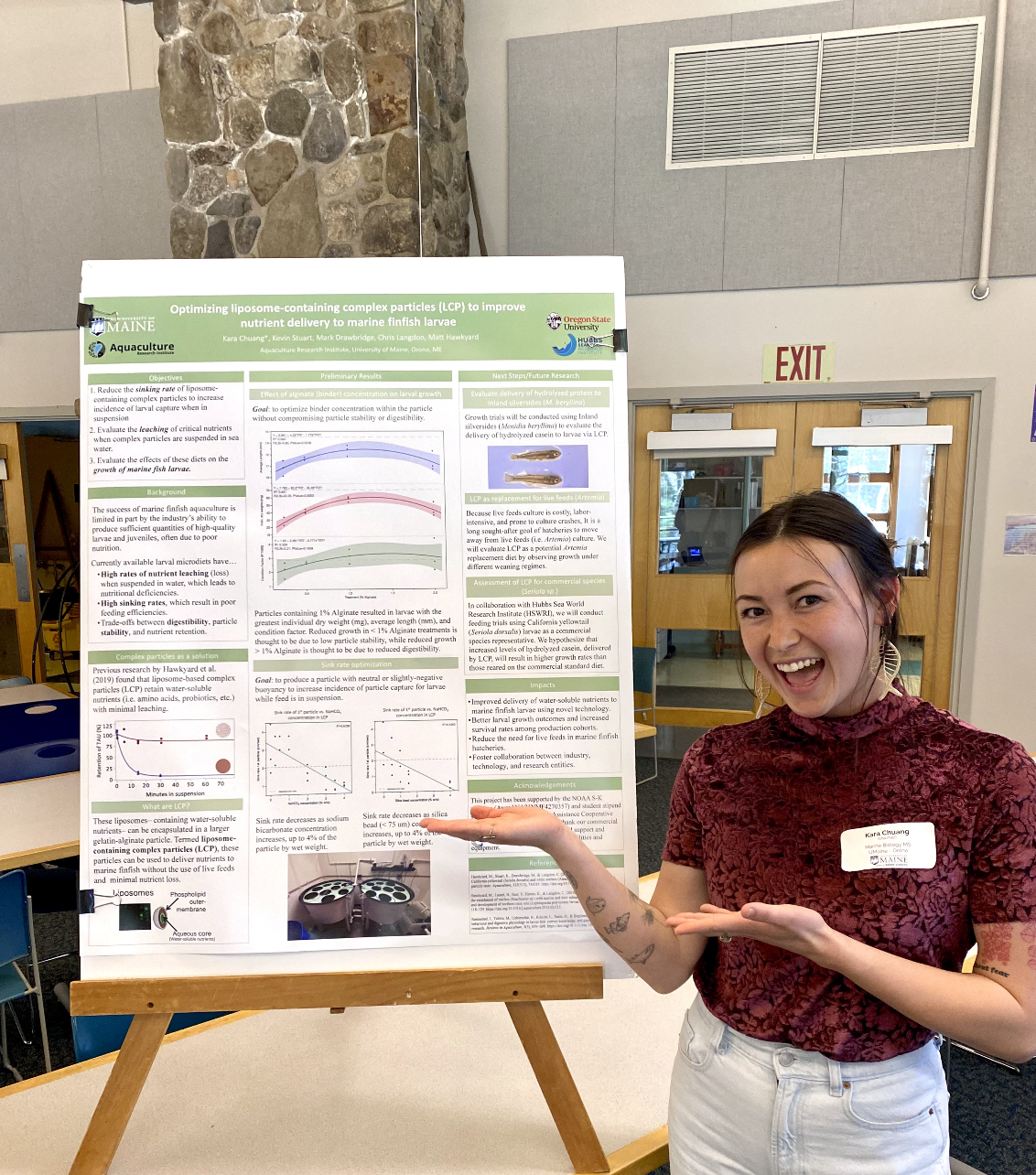

The beginning of May at the Darling Marine Center welcomes us with blooming birches, warmer sun, and the end of another academic year, giving graduate students the opportunity to present their research. This past week, more than 60 School of Marine Sciences graduate students, some affiliated with the Aquaculture Research Institute (ARI), gathered for a symposium in Brooke Hall to highlight innovative work in their fields of study. Presentations covered a wide range of topics, from genetics to environmental monitoring, demonstrating the diversity and depth of research conducted at ARI. Beyond the statistics and data, the research presented by these graduate students has a broader implication for climate change, environmental management, and environmental policy. With both warming waters and a growing aquaculture sector in Maine, it’s critical to understand our coastal ecosystem and the communities reliant upon them.

Shellfish research was the basis for many talks at the symposium as Chris Noren, Jamie Peterson, and Tom Kiffney focused on the future of scallops and oysters. Noren, one of Damian Brady’s students, discussed the importance of understanding how scallop growth oscillates with temperature and season for sustainable development of the sector. Peterson, a student of Paul Rawson and Kiffney, another student of Damain Brady both concentrated on oyster development. Kiffney discussed the difference between diploid and triploid oyster growth in the Damariscotta River. Triploid oysters, containing three sets of chromosomes instead of two (diploidy) are nearly sterile, allowing them to grow faster and larger, as energy is not spent on reproducing. Peterson spoke about oxylipins, looking at the impact they have on early stage development. Oxylipins, produced by marine diatoms, algae, and certain bacteria can cause abnormalities or be toxic to marine organisms. Understanding the detrimental impacts of oxylipins can provide useful information for larval rearing in hatcheries. Bobby Morefield, working in Heather Hamlin’s lab presented his work examining the role that sex pheromones can play in the mitigation of sea lice infestations on Atlantic Salmon.

Impacts of climate change and aquatic animal health were also presented at the symposium. Kate Liberti and Rene Francolini, both working in the Brady lab, underscored the importance of understanding the ecology and oceanography of Maine’s coastline. Liberti talked about temporal and spatial differences in aragonite saturation in Casco Bay. Aragonite is a form of calcium carbonate, necessary for shellfish growth. Organisms may be stressed and have a harder time forming their shells when aragonite saturation levels fall below one. These lower levels of aragonite saturation are due to increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, so following the processes and changes impacting carbon dioxide can be useful as an indicator to understand how aragonite saturation state is changing in Casco Bay. Francolini spoke about kelp forests and understanding genetic connectivity of different populations along the coast. Genetic information at the population level can provide useful insight into how different populations of kelp will react to changing oceanic conditions. This baseline knowledge is imperative as kelp is an essential nursery habitat for many native species along Maine’s coastline. Another one of Brady’s students, Sydney Greenlee, honed in on early detection of harmful algal blooms (HABs) using environmental DNA (eDNA). Pseudo-nitzschia australis, a marine diatom, can cause the blooms which can result in amnesic shellfish poisoning in humans, as well as pose negative health impacts to marine mammals and seabirds. Prior methods made it challenging to distinguish between toxin and non-toxin producing Pseudo-nitzschia species. eDNA can serve as a rapid detection and quantification tool for these HABs, alerting managers to the presence of diatoms in their samples so they can close shellfish harvesting before toxins are present.

Kazu Temple’s, a student of Ian Bricknell, is looking into the parasitic relationship of Profilicollis botulus, a prevalent parasite in green crabs and the impact this may have on the native eider duck population. The European green crab, an invasive species posing challenges to shellfish growers and harvesters in the intertidal, is the host of the parasite Profilicollis botulus known as a “spiny-headed worm.” When other animals such as the eider duck eat green crabs, they also become infected. Knowledge of this parasitic interaction between green crabs and other organisms is useful, as green crabs have been suggested as bait for the lobster industry and can also provide informative data about the spread of green crabs as an invasive species across different regions in Maine.

The breadth and future impact of the research presented by these graduate students is impressive. This symposium serves as a reminder of the enormous potential this new generation of scientists has to shape the future of our marine ecosystems and coastal economies.