ARI Extern Andrew Hoffman Maps the Future of Shellfish for Brunswick, ME

By: Meghan Nadzam

Thousands of clams. Mud and sediment everywhere. Hungry, invasive crabs. A constantly changing climate. These are things Andrew Hoffman deals with every day.

Hoffman, a Bates College student from Oak Park, IL, works for the Town of Brunswick Coastal Resources Department on shellfish conservation through UMaine’s Aquaculture Research Institute (ARI) externship.

The Coastal Resources Department, managed by Dan Devereaux, creates policy and is responsible for the conservation of Brunswick’s shellfish: razor clams, American and European oysters, soft-shelled clams (Mya arenaria) and hard clams/Northern quahogs (Mercenaria mercenaria). Devereaux and Hoffman work together alongside Marine Warden and Harbormaster Dan Sylvain and Community Outreach Representative Ashley Charleson. Together, they find avenues to best conduct ecological restoration to sustain, conserve and enhance Brunswick’s historical and ecologically sensitive areas and species.

Maine and Massachusetts are the only two states left in the nation where shellfish are managed on a local level. Local management allows for a more closely observed interface with the ecosystem’s health in the face of climate change as shellfish are keystone species in the near-shore ecosystems.

According to Devereaux, the Coastal Resources Department licenses 65 commercial clam harvesters to dig hard and soft-shelled clams. In the town’s economy, clamming is valued at $13 million and supports 212 jobs including wholesale and retail shellfish dealers, truckers, packers and shuckers.

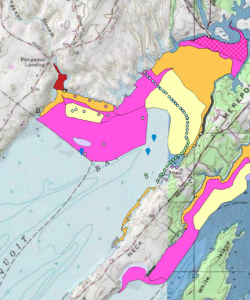

How does Coastal Resources maintain such a large industry? The department opens and closes mudflats to clammers based on the density and productivity of clam populations. Hoffman’s externship involves mapping mudflats using an interactive website available for anyone interested in harvesting clams. With this website, shellfish farmers and businesses can accurately locate and access open mudflats with high densities of harvestable clams.

“A more fancy and shorter term for what we do is marine spatial planning. Once we get the maps created, it all becomes really useful in terms of what resources are in the area, how we want to develop that area, should we farm

or not farm that area, and which landowners we need to focus on that are part of the solution to climate mitigation. In theory, if we can find those non-productive areas that are consistently non-productive and develop shellfish farms there, it will help wild populations of clams around those areas,” Devereaux says.

To conduct the mapping, Hoffman uses a database called Geographic Information System Mapping, or GIS. GIS helps organize geographical data into maps with software tools for managing, analyzing, and visualizing the data. With GIS, Hoffman can include layers and points of interest on a map based on whether or not the area is open or closed to clamming or if clam productivity and density is high or low. Hoffman hopes to create an interactive map with detailed notes and research similar to the Community Intertidal Data Portal by Casco Bay Regional Shellfish Working Group, but focused on the area surrounding Brunswick. Hoffman hopes to create a story map to show viewers how to interact with the GIS map, explain what each layer is on the map, and why it’s important.

How does one map clam density? The entire area is surveyed every other year, and roughly half of the maintained 1,600 acres is open each year for harvest. To survey such a wide area, Hoffman and coworkers go out into the mudflats via airboat. They collect GPS points along the perimeter of every mudflat containing harvestable clams. Hoffman makes notes on soft-shell and quahog density. GPS points are imported into GIS to create a map, and Hoffman manually enters all the notes for each point. Using a survey method done for almost 60 years in Brunswick, Hoffman, Devereaux and Sylvain dug 2’ plots on a 200 ft. transects along the mudflat growing areas, providing a random survey of clams and their productivity, measured by size of the shell.

“Right now, the legal harvesting size of a soft-shell clam is two inches. We want to see what’s actually out here, whether it’s a few millimeters or really big ones. We’ll determine an average of all the sizes, and then we’ll see if it’s worth keeping the mudflat open or closed,” Sylvain says.

However, temperature and predation are threatening clam survival in these mudflats. Soft-shelled clams and quahogs have a very active lifestyle when the water is warm, allowing them to move around and spawn. Unfortunately, warm temperatures rising due to climate change also allow for the invasive green crab (Carcinus maenas) population to thrive and be very detrimental to clam populations.

Hoffman’s externship also includes monitoring the invasive green crab populations to support shellfish conservation. With traps set out along Brunswick’s coast, Hoffman pulls up roughly 500 green crabs twice a week.“The best thing we can do is leave the crabs in a bucket until they die and then compost them. There’s nothing else to do with them. There’s no demand for them in markets. It’s pretty crazy,” Hoffman says.

To make up for the losses of shellfish, Hoffman and Devereaux are planting 500,000 baby quahog clams raised from the larva stage at Mere Point Oyster Company where Devereaux is a part owner. “Their survivability increases almost up by 50% if you grow the quahogs over 10mm wide. We float them at the surface in protected nets at one millimeter and we raise them to 10-15mm by the fall. We’ll give them to fishermen and clammers, and they’ll take them out to broadcast them in areas where there needs to be more clam production,” Devereaux says. But the loss of shellfish to crabs is not the only issue Devereaux and Hoffman deal with: citizens of Brunswick need to be open to the idea of clam restoration for the sake of the waterways.

“Productive acres of mudflats could provide more shellfish to the market, and together, they could provide more ecosystem services than, say, 1,000 acres of sub-productive area. It’s important that we try to keep track of that,” Devereaux says. “That’s what scares people particularly when you get out to these dynamic ecosystems because we need to identify activities that can coexist in a fisherman’s world. That’s a delicate balance, and it requires having really hard conversations with fishermen and other users of the bay about what’s best for the bay. The real question is how do we start to engage in that conversation?”

Similar to Devereaux, Hoffman has found a deep interest in conservation and hopes to engage further with it as he enters his senior year at Bates College. “I am definitely interested in coming back to Maine when I graduate. Aquaculture and GIS are subjects I’m really interested in, and Maine is a great spot for that. This externship gives me a lot of different experience in conservation, and I hope to find something like it in the future,” Hoffman says.