Solarization and the Soil Microbiome

Grace Smith, Undergraduate in Molecular and Cellular Biology

Sonja Birthisel, PhD Student in Ecology and Environmental Sciences

Eric R. Gallandt, Professor of Weed Ecology and Management

A soil microbiome consists of tiny organisms such as bacteria, archaea, fungi, and protists that impact plant life. Beneficial microbes decompose organic molecules, rendering them usable by plants and protect against harmful microbes. Conversely, pathogenic microbes can have major detrimental effects on crops.

In June through August of 2016, we expanded our study of solarization (see previous blog posts about solarization for weed control) to examine the effect of solarization on soil respiration and specific populations of beneficial microorganisms: general bacteria, general fungi, Bacilli, and fluorescent pseudomonads.

A picture of a rose bengal agar plate which was used to select for the growth of general fungi in our experiment.

The Experiment:

Solarization was performed for two and four weeks in a field and closed hoop house at Umaine Greens, located on the campus of the University of Maine, Orono.

Plots were rototilled and irrigated prior to application of previously used clear polyethylene mulch. Temperature was recorded throughout and soil samples were collected at the beginning of the experiment, at plastic removal, and 5 & 14 days after plastic removal for microbial analyses.

Temperature:

Solarization caused average temperature increases of 4 and 7℉ in the field and hoop house, respectively; furthermore, maximum temperatures increased by 10 and 15℉. The maximum temperature increase is of interest because prior research indicates that maximum temperature may be more important than average temperature in pathogen control. The dip in soil temperature between July 6th and 13th (labeled “A” in the figure below) corresponds with cool air temperatures during those days (Bangor International Airport, NOAA).

Temperatures over the course of four weeks of treatment in the field and hoop house. CON = control ; SOL = solarized.

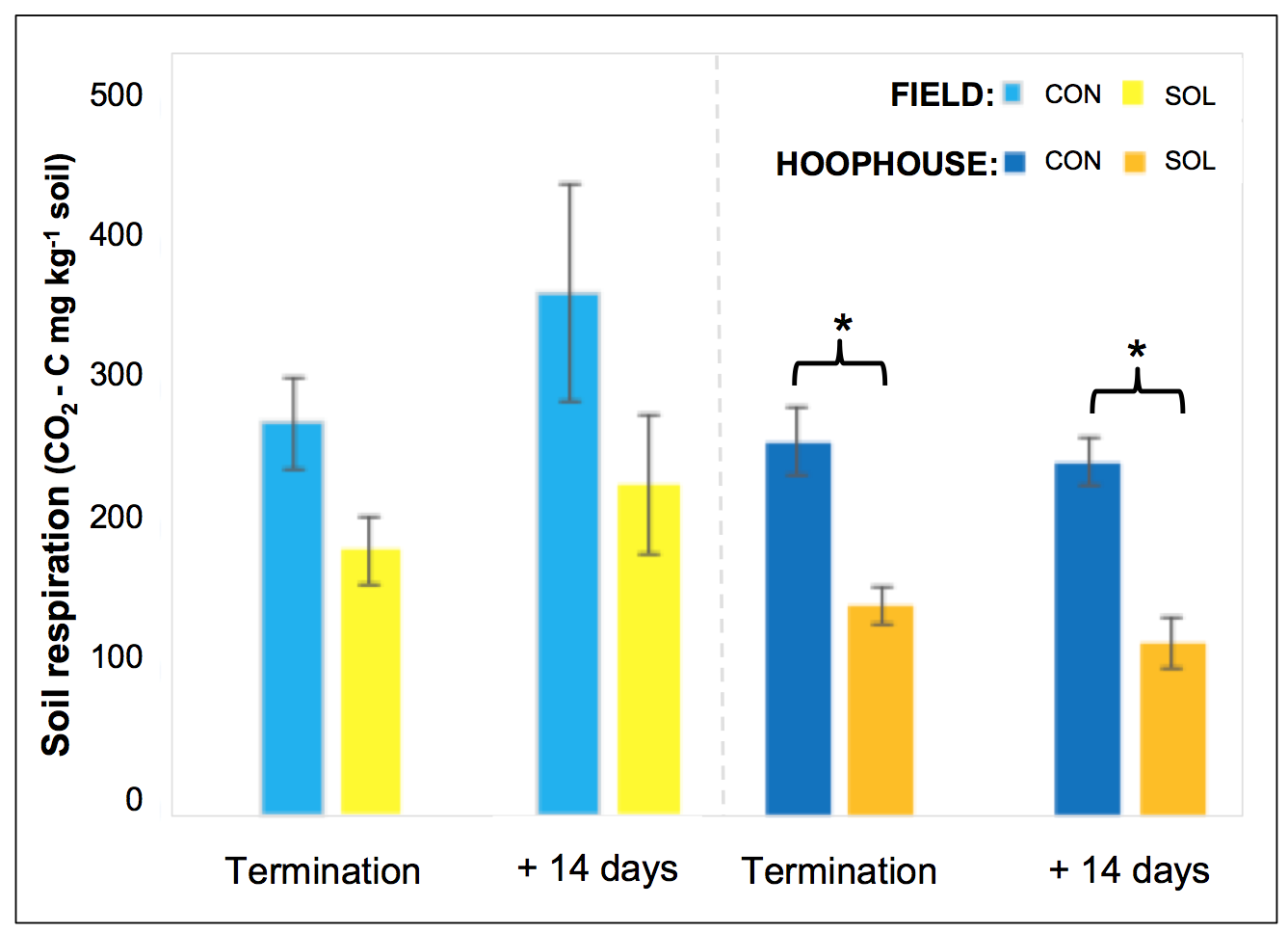

Soil Respiration:

Soil respiration was measured to serve as an estimate for total microbial biomass, an indicator of soil health. We found that solarization decreased soil respiration to a minor extent in the field, and more significantly in the hoop house. We originally predicted that soil respiration would be reduced while plastic was in place, but would bounce back to normal levels by two weeks after plastic removal. Since this was not the case, it would be valuable in the future to test how long it takes for soil respiration to fully return to control levels.

Soil respiration in the field and greenhouse at treatment termination (time of plastic removal) and 14 days after termination. * = significant difference.

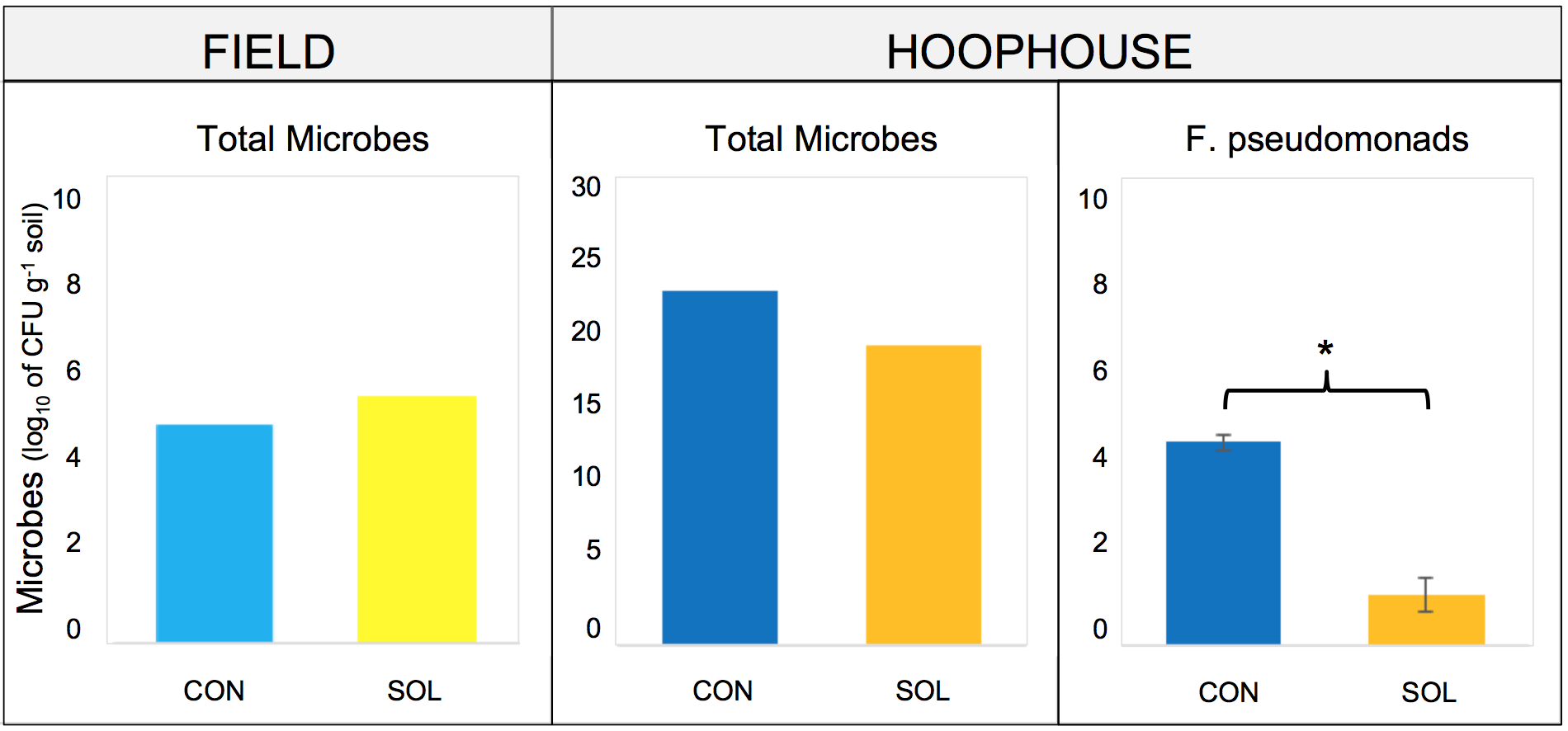

Populations of Specific Beneficial Microbes:

In this experiment, we measured populations of four beneficial microbe groups: general bacteria, general fungi, and rhizobacteria Bacilli and fluorescent pseudomonads. Many general bacteria and fungi decompose large indigestible organic molecules into smaller, plant-useable nutrients. Fungi increase soil water holding capacity by growing hyphae: long, threadlike filaments. Some Bacilli convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia making it available to plants, and some fluorescent pseudomonads release antibiotics that decrease populations of plant pathogens.

The good news first: field solarization did not harm any of these four groups of beneficial microbes we were able to grow in the lab. Under the hotter temperatures in the hoop house, there was a slight decrease in these microbes overall due to a decrease in fluorescent pseudomonads; the other groups of microbes were not significantly impacted.

Number of soil microbe colonies grown from soil collected 5 days after treatment termination in the field and hoop house. * = significant difference.

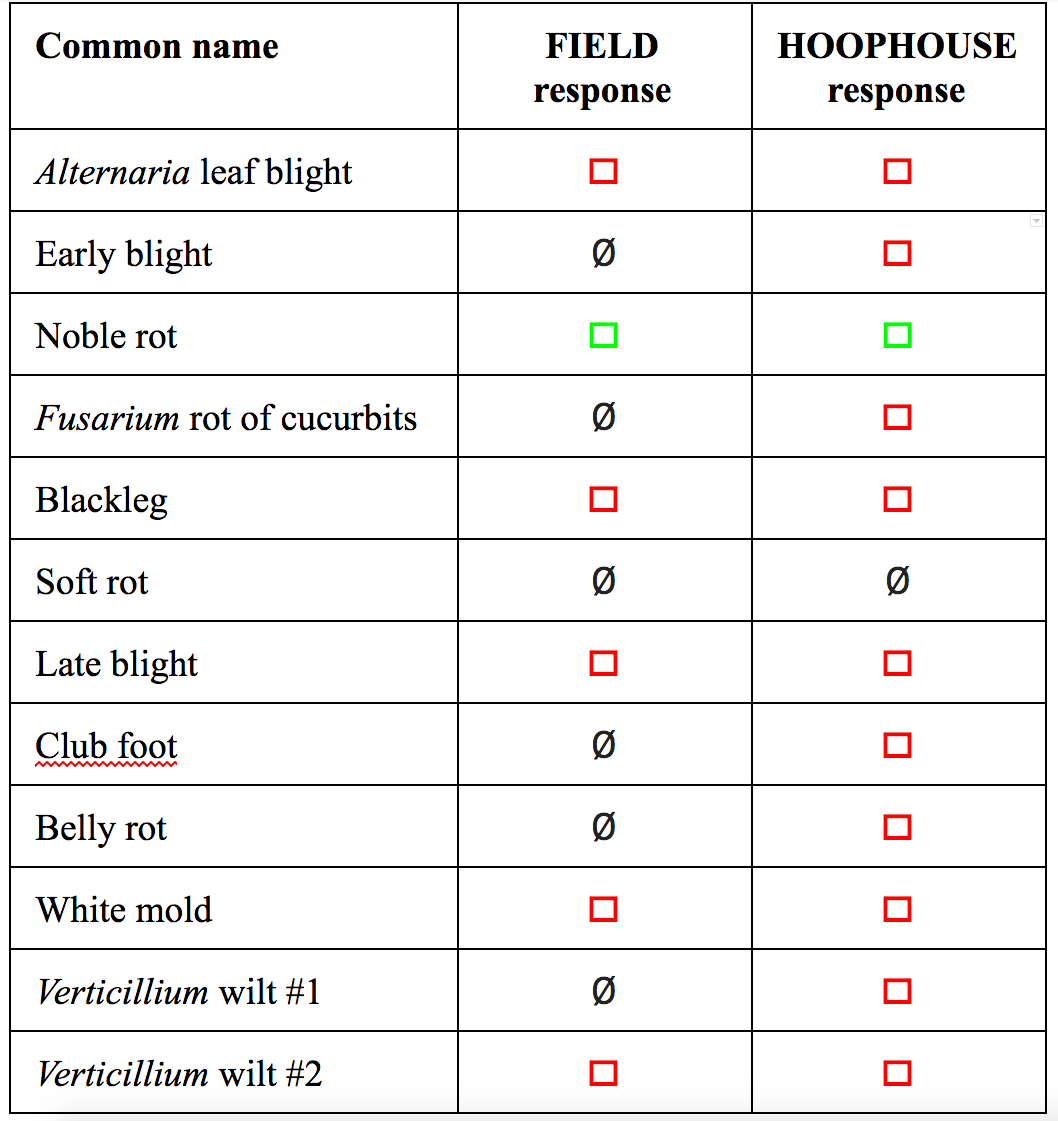

Literature Review of Expected Pathogen Response to Solarization:

Measuring the effects of solarization on plant pathogens was beyond what we could accomplish in this experiment. However, to get an idea whether pathogen control with solarization is theoretically possible in Maine, we reviewed papers of known pathogen responses to temperature, and compared this to the maximum temperatures measured in our experiments. Nearly half of the pathogens we investigated are predicted to decrease in number under temperatures we measured in our field, and over three-quarters are predicted to decrease with temperatures achieved in our hoop house. The only included pathogen that we predicted might increase in response to solarization is noble rot, also known as gray mold, a fungus that affects grapes and other horticultural crops. These theoretical results need to be backed up with real-world experiments in Maine, but provide a preliminary indication that solarization could contribute to not only weed management (see past blog posts), but pathogen control as well.

Potential effect of solarization on some pathogens of vegetable and horticultural crops in Maine, based on temperatures measured in our experiments and known temperature tolerance of these pathogens. ?: pathogens that may decrease in response to solarization; ?: pathogens that may increase in response to solarization; Ø: pathogens that are expected to be unaffected by solarization.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that solarization did little harm to beneficial soil microbes in an open field, but in a hoop house soil respiration and populations of the beneficial fluorescent pseudomonads bacteria were significantly reduced, at least in the short term. Further research is needed to see if these effects are long lasting and have subsequent impacts to crop growth. Based on the soil temperatures we measured, it is possible that solarization could contribute to plant pathogen control in Maine, though more research on this topic is needed to confirm this.