Farmington, ME

Introduction: Values to Value

This webpage explores the value of materials circulating through a reuse economy and the values of reuse organizations and businesses that keep those materials moving. The double entendre of “Values to Value” communicates both the relationship between organizational values and the assessed, material worth of reused goods, and also the inherent value of Maine’s cultures of reuse. While our group’s focus is Farmington, we also consider reuse organizations and waste management facilities throughout the State of Maine. As we conducted ethnographic research, we encountered many kinds of reused materials. The assessed value of these materials seemed to be largely subjective: dependent on diverse social, cultural, and economic perceptions. The value that is attributed to these materials is related to the cultural values held by people moving them across Farmington, the State of Maine, and the global community.

This webpage explores the value of materials circulating through a reuse economy and the values of reuse organizations and businesses that keep those materials moving. The double entendre of “Values to Value” communicates both the relationship between organizational values and the assessed, material worth of reused goods, and also the inherent value of Maine’s cultures of reuse. While our group’s focus is Farmington, we also consider reuse organizations and waste management facilities throughout the State of Maine. As we conducted ethnographic research, we encountered many kinds of reused materials. The assessed value of these materials seemed to be largely subjective: dependent on diverse social, cultural, and economic perceptions. The value that is attributed to these materials is related to the cultural values held by people moving them across Farmington, the State of Maine, and the global community.

We suggest that Farmington and the greater Maine community are exemplary cases to consider as policymakers (municipal, state, or national) incorporate reuse into environmental and economic planning — a policy pathway that emerges out of the shared values and lived practices of reuse.

We suggest that Farmington and the greater Maine community are exemplary cases to consider as policymakers (municipal, state, or national) incorporate reuse into environmental and economic planning — a policy pathway that emerges out of the shared values and lived practices of reuse.

This webpage is a product of digital ethnographic methodology, incorporating interviews and surveys with photography and audio editing — but we also hope that the ethnographic process itself is apparent. This project would not have been possible without the contributions of numerous store owners, agency employees, non-profit organizers, waste managers, and reuse customers who granted us their time, energy, and insights. What follows are examples of the social values that motivate the capture and continuity of value in reused goods.

Literature Review

How do you assess a “good deal” for used products? Is it the quantity, bulk, or volume? Is it the quality or durability? Or is it something else still? Consumers have many ways of finding value for an item, and sellers have equally diverse ways of determining an item’s value. This is especially true in Maine’s reuse economy where prices for similar items can vary greatly between consignment shops, thrift stores, and swap shops. But, with such a varying definition of value, how do buyers and sellers assign and decide the worth of an item? According to Carsky et al., “The term quality can be broadly defined […] However the many definitions can be subsumed under two broad classifications: perceived quality and objective quality” (Carsky et al. 1998: 1). Within the reuse economy, both of these definitions of quality are important factors in perceiving the value of an object. For example, a beat up, wooden ladder leaning on a shed full of antiques along Route 2 would not necessarily cost 50 dollars to make (its objective quality); however, its value is perceived with many potentials by each buyer and seller (its perceived quality).

This idea is reinforced by a Danish case study, conducted by Zacho et al. In reference to value assessment, they state, “Values also have to do with relative importance, worth or usefulness that individuals or groups attach to things. The term ‘value’ is thus highly unspecific and covers more than just the monetary worth of something” (Zacho et al. 2018: 299). They suggest that the production value of an object only scratches the surface of what makes an item for sale valuable. It is clear that within the reuse economy, “value” and “worth” are both highly contextual, unique to the values and motivations of social reuse community systems made up of both buyers, sellers, and organizers.

Berry et al. (2019) explore one of the New England area’s social and cultural networks of reuse — the State of Maine. The authors recognize that Maine’s cultures of reuse are based not only on economic rationales but also their unique sense of place, in addition to their social and environmental history, culture, and character. The cultures of reuse organizations and consumers in these places demonstrate values through practice. Martin and Upham have argued that “far from being value-free, organizations in practice reflect, enact and propagate values” (2015: 205). Our study, therefore, observes the practices of valuing reused goods in Maine as a reflection, enactment, and propagation of particular contextual value systems. We agree with Berry et al. that, “in an era of climate change, uneven development, resource depletion, and growing waste streams, reuse is being promoted as a key strategy for moving toward more efficient and sustainable circular economies that make full use of resources and goods already” (Berry et al. 2019: 2). We hope to shed light on diverse value systems encompassing some circular economies we explored in Farmington, Maine’s culture of reuse. These are values to value.

Photo Essay

This photo essay follows the prolonged quality and life that Mainers gain from products in reuse economies and the many options that can be explored before the product reaches the end of the road. In most economies and consumer systems, items are used until the buyers deem them fit to toss. The items most commonly have one life, one purpose, but when put into the reuse system, they may have numerous owners. Mainers do very well with extending extra life from products within its reuse economy, creating extra value from the same item multiple times.

Audio Clips

This is a story from a thrift store owner in Farmington demonstrating how donations are sorted according to their assessed value. The interview participant then traces the process of how items deemed as surplus are sorted, processed, transported, auctioned, and sold. Despite the attempted circularity, surplus items (which may still valuable) are backed up and on hold.

Below is an audio clip of a short interview we conducted at one of Farmington’s thrift stores. As this project is emergent out of a course in ethnographic methodology, we keep the audio in a (nearly) unedited state to demonstrate the process of ethnography to accompany the product of ethnography. As you listen, consider some of the values that motivate this customer’s participation (or not) in Farmington’s reuse economy, including cleanliness, frugality, a commitment to low prices, product durability, and “unique” aesthetics.

“I’ve just always loved to make things with my hands. And I was a builder, and I broke my back, and I had to have surgery. So I had to do something different. So I started doing jewelry work. I trained for a year with an elderly jeweler up in Ellsworth Maine. A lot of [jewelry] repair is done the same way they’ve been doing it for hundreds of years. I mean now we may use some more modern tools. I have a laser welder; it’s an $18,000 machine doing real intricate work, but I still use my torches here and the welder. It’s all basically the same thing; it’s been done for thousands of years.”

Research Findings

In our study of the value ideologies within the State of Maine, we interviewed participants and managers involved in various sectors in reuse economy. While we conducted interviews all around the state, the majority of our interviews were conducted in Farmington — a vibrant and distinctively “Maine” town. We spoke to the owners and operators of establishments like the Farmington Thrift Store, Mercantile Antiques, 3DGames, and Mainestone Jewelry. When asked to attest to the value and quality of the goods they receive and sell, they responded in a variety of ways. Almost all of those we interviewed spoke about their perceived value and objective value they recognize in Maine’s reuse economy. For example, a manager of the Farmington Thrift Store states,

“The donations have changed quite a bit. We get more trash than we’ve ever gotten before… we get really nice stuff too, don’t get me wrong, but we get more kinds of equipment that don’t work. You know, people dumping things outside — those kinds of thing happen more than they ever have.”

The struggle to sort through and find reusable items in an economy where things are designed to break can be difficult. To this end, in an interview, the owner of Mercantile Antiques said,

“If people pick up an old kitchen gadget that’s still unusable, they feel great that they’re participating in the reuse economy and being environmentally friendly. We always joke about how that is the ultimate recyclable because the old things were made so well that they still work and it’s low tech…it’s not like ‘oh five year warranty’ … it was made in another country, and you just can’t get anybody to fix it. It still works because it was made low tech. So that’s definitely a big selling point for our industry […] Not only is it a good value because it was made well years ago; it still exists, and it’s in one piece, which proves it’s value.”

So while there may be steady declining product quality in some new goods, many customers and managers participating in the reuse economy are searching for and recapturing value in creative ways.

Rummaging through the Farmington community, it was easy to see that insights from Berry et al’s 2018 article about Maine’s reuse practices held true as evidenced in our ethnographic journey. Several Farmington reuse retailers were thriving and growing through the years. They experienced changes and overcame challenges to remain in business, attributed to their resourcefulness, flexibility, and unwavering belief in the value of the products sold. Many of the thrift stores are mission-driven, non-profit social enterprise businesses that also sell previously owned goods in their original form.

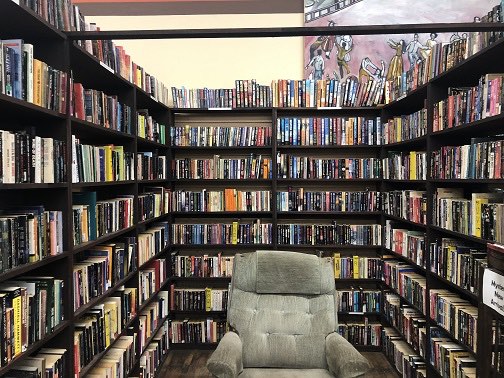

One of the shop owners specifically expressed her lifelong passion and appreciation for antiques and articulated her awareness about the history of objects, their potential value, and Maine’s traditions of reuse. In Twice Sold Tales, a used bookstore in Farmington, the owner operates his business according to what Berry et al. might call an “intentional and active strategy focused on resistance to consumer ideology” (Berry et al. 2019: 4–5). He stated that he has lowered his profit margin; breaking even has carried him through challenging economic times. His store invites sociality — two friends stopped by during our interview, just to visit, and we were told this happens regularly. This is similar to the community at 3DGames, a store that specializes in both the trade and repair of video games and video game consoles. At the store, one customer reflected on a recent social event, “We had all of these tables in the back room here filled and then we had two more of these tables in the showroom. And it was just packed in here all day.” This is a community that has “long demonstrated vibrant and persistent cultures of reuse” (Berry et al. 2019: 10).

Our fieldwork experience confirmed that Farmington’s reuse economy is thriving, and motivated by diverse values and value: including (but certainly not limited to), the quality and economic value of the objects themselves and their lifespan, the mission-driven social programs of non-profit organizations, resistance to consumer ideology of consumption and disposal, and the cultivation of social spaces for welcoming the greater community.

Researcher Reflection: Camryn Hammill Nordfors

The University of Maine Ethnographic Field school (summer 2019) offered me my first true anthropological field experience. It’s solidified my decision to be an anthropologist and it’s ignited my passion for this work, that alone will always make this experience special to me. However, I would give this program my highest praise regardless of my time in the field. It has taught me an extraordinary amount about the field process and how to conduct myself in anthropological studies. I learned many priceless techniques in such a short period of time. Among many things I learned how to conduct experiments with human subjects — and achieve certification for it — how to conduct a formal interview and many digital methods of observing and recording ethnography.

This course was not simply a brilliant academic experience for me. The topic of reuse and climate change has always been a very big interest of mine. In a way, this course brought the two issues together into one whole. This course ignited (or re-ignited) my passion for fighting climate change. As I’ve always held a lot of concern for the environment and a deep love for nature – specifically the gorgeous natural wonders we experience as Mainers. I’m frightened and concerned that climate change and global warming could take the opportunity to enjoy these wonders away from my children and grandchildren. This trip opened my eyes to the negative behaviors that even I am guilty of; however, it also resolidified my drive to make a big change in the world.

Researcher Reflection: Dominic Piacentini

Sometimes during the life of this project, I felt similar to the used books and bicycles we were studying: shuffled around and moving between different stores, shops, and waste facilities across the state — through Orono, Orrington, Bangor, Brewer, Augusta, China, Farmington, and Wilton. It was at times both exhausting and overwhelming. I remember the smells of the Penobscot Energy Recovery Center, the sounds of the China Transfer Station, and the look of the Farmington Thrift Store. I remember being surprised by the sheer amount of reuse organizations. There are of course businesses organized entirely around the sale of reused goods, but there are many other shops and organizations that move both new and used goods (like Brewer’s Affordable Restaurant Equipment) or repair goods (like Farmington’s 3DGames). The scale of reuse in Maine is expanded by other, maybe less obvious, actors: used book libraries in Wilton’s Lake Wilson Inn or the antique wholesalers and auctions supplying storefronts with a fraction of the goods they are moving. There is a bulk and heft to reuse in Maine. Seeing this bulk first hand and sometimes participating in its movement made me more aware of the enormity of it all.

I was also frustrated. Despite the vibrant and active practice of reuse in Maine, a surplus remains. So many items are being shipped overseas or sent to landfills or waste recovery centers. Farmington and other regions of the state are doing a great job at reducing material traffic to landfills and the production of new carbon-intensive goods, but is it enough?

Researcher Reflection: Kerry Sack

I thought the field visit research process itinerary was a very thoughtfully sequenced process, starting with our own campus first, then moving out to our local area community reuse and repair vendors in Bangor and Brewer and then our visit to our region’s waste processing center at PERC.

We researched more site visits than we had time to visit, and several were added as suggested by our informal, un-taped discussions with area residents, or after our tape recorders were turned off. We were told that the local Farmington radio station allows folks to call in about the stuff they want to sell, and they put these on the air several times daily. We also discovered several hidden sources of reuse in retailers such as the fabric store having a quality used furniture room, or the motel’s well stocked bookshelves (suggested donations benefit the town library).

I’m not close to even having 20/20 hindsight, so I’m not sure if it was my being so new to ethnography, and/or it was my not seeing and/or comprehending the importance of utilizing the literary reviews to shape and create our framework for the extended field trip to Farmington, but I suspect that this neglect/ deficit/oversight may have contributed to our interview questions falling short of capturing more personally/professionally storied and meaningful information instead of the i.e., data/business history/customer base category of questions that we asked in our interviews. I still feel quite unacquainted with the correct format and citing documentation for academic papers.

Dominic’s team leadership was excellent, and there were many times when I would have felt lost without his help, both on the field trip and most especially in preparing the final project. I wish I didn’t care but am extremely disappointed about not sharing (not having time for) the selection of the pictures part of our project for the webpage. I was surprised how much I enjoyed taking pictures again, after so many years.

I am behind in writing field notes from a few sites we visited. If the grant project will need those, I will make sure to get caught up and submit those, too.

I visited the Old Town Transfer Station on my own because that is in my town and I happened to be driving by when it was open. If it will be helpful for the project, I will write up my field notes and submit the pictures as well.

Thank you for accepting me into this class. I loved it and learned a lot. I hope that some of what I contributed may be helpful going forward.

Bibliography

Berry, Brienne, Jennifer Bonnet, and Cindy Isenhour (2019). Rummaging through the Attic of New England. Worldwide Waste: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2(1), 6, 1–12.

Carsky, Mary L., Roger A. Dickinson, and Charles R. Canedy III (1998). The evolution of quality in consumer goods. Journal of Macromarketing, 18(2), 132–144.

Martin, Chris J. and Paul Upham (2016). Grassroots social innovation and the mobilisation of values in collaborative consumption: A conceptual model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 204–213.

Zacho, Kristina Overgaard, Mette Mosgaard, and Henrik Riisgaard (2018). Capturing uncaptured values — a Danish case study on municipal preparation for reuse and recycling of waste. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 136, 297–305.