Machias, ME

Introduction: Care and Community

As people sorted donated items at a local transfer station, priced used furniture and household goods, or sold antiques at a local flea market, they were engaged in the work of caring. This work is often uncertain. Many stores are open seasonally, reliant upon tourists who come once the weather warms up in the spring. Other stores focus on local clientele, but with an economy that many describe as struggling, finding customers can be a challenge.

Nevertheless, Machias has a vibrant reuse economy that seems to hum under the economic surface of the town. Shops are tucked away in garages, houses, and sometimes only open by request. We observed that business owners and volunteers are connected through a supportive, informal network that helps them to promote each other and help one another survive.

These themes of care and social network support are illustrated through the stories, images, and experiences shared by our research participants. We are grateful for their openness and patience as we learned together.

Literature Review

Themes of care and supportive social networks are abundant in the academic literature on reuse marketplaces and second-hand economies. Albinsson and Yasanthi Perera (2012) study “really really free markets” (RRFMs) – sites where participants exchange goods at no cost. They find that participants in these markets exhibit not only an interest in gaining access to free materials, but also – and perhaps primarily – a “desire to enact social change while fostering personal and community well-being through participation in alternative marketplaces” (2012:307-308). The authors observed “a genuine care for others” (2012:310) among attendees in RRFMs, and note that community-building was an important outcome for many participants. Ideas of caring and supporting community also emerge in contexts where goods are exchanged for money. Larsen’s (2019) work in a non-profit thrift store documents how both objects and people are cared for in the process of exchanging used goods. The thrift store has an explicit goal of care as it raises awareness and money for people living with HIV and AIDS. Yet beyond care for people, Larsen (2019) documents the ways in which objects are valued and loved. He observes a man donating boxes that “all contained his late wife’s clothes and shoes. She had recently passed away and he was getting rid of all of her clothes” (2019:157). This process was laden with care and emotion, where the objects clearly still hold value and an essence of their former owner within them. In detailing how items are sorted, priced, and judged in terms of quality, Larsen notes that processes of care and valuation are threaded throughout the process of donating and purchasing goods in thrift stores. While those who are letting go of cherished goods may experience a sense of loss, Larsen also finds that shoppers create new forms of care and connection to objects. For Larsen, the thrift store is more than a store, but also a place that is “able to create economic, social, and emotional value” (2019:166). Berry and colleagues (2019) find that care and social network support are threaded throughout Maine’s reuse economies. They note that locals “piece together livelihoods with what is at hand: seasonal jobs, small businesses, and informal exchange networks” (2019:5). These networks in Maine’s reuse economies are essential to the survival of not only the businesses, but the livelihoods of the owners as well. People collecting materials are “doing society a great service, collecting and salvaging goods with value, because one never knows when they might be needed” (2019:2). By ensuring that goods are available, people working in this area are housing items for when the community may need them. In a place where economic upheaval might suggest that people are fighting for their survival, we see in the literature that people band together when most needed, surviving and providing together. Even in the face of economic challenges, motivations for participating in reuse economies is complex, and is often linked to ethics of care and a desire to support others.

Audio Clips

Photo Essay

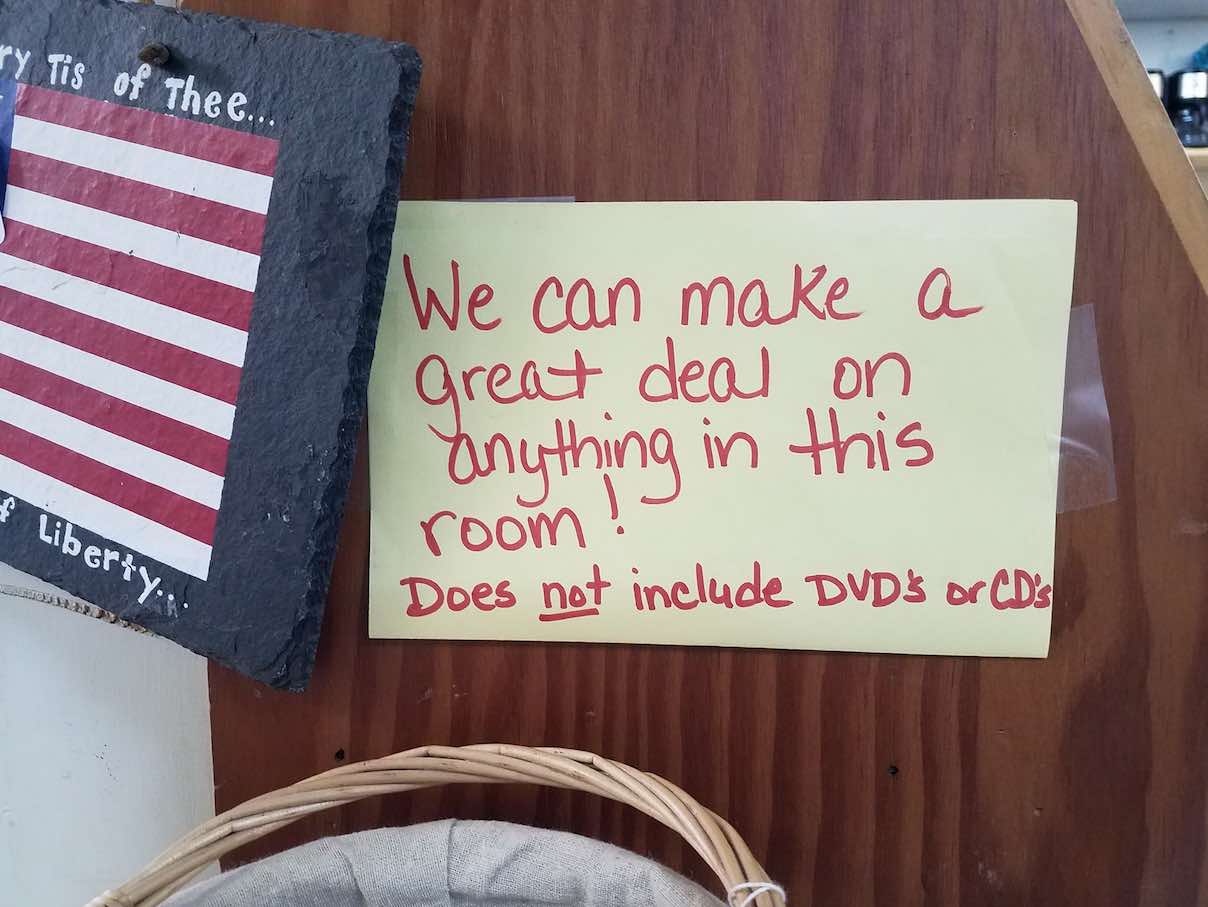

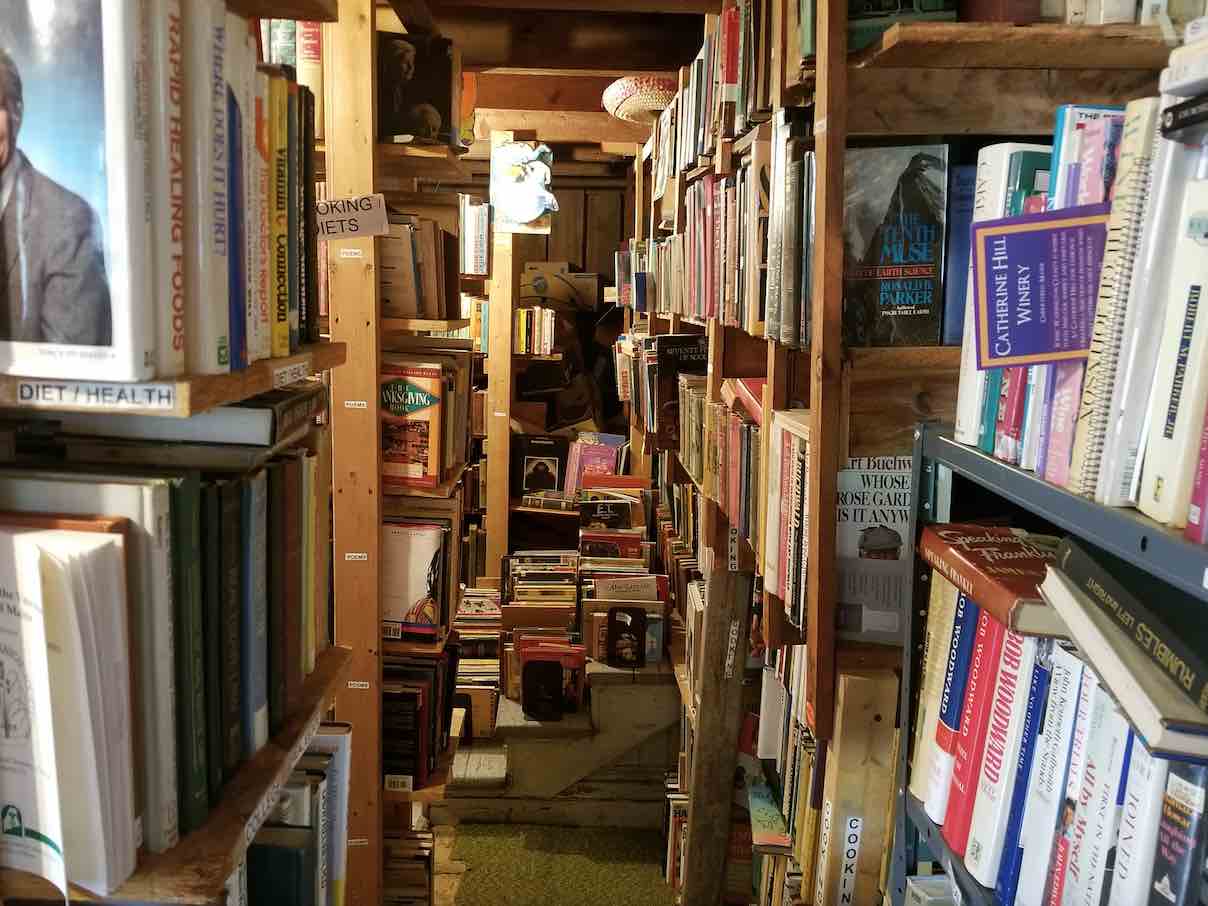

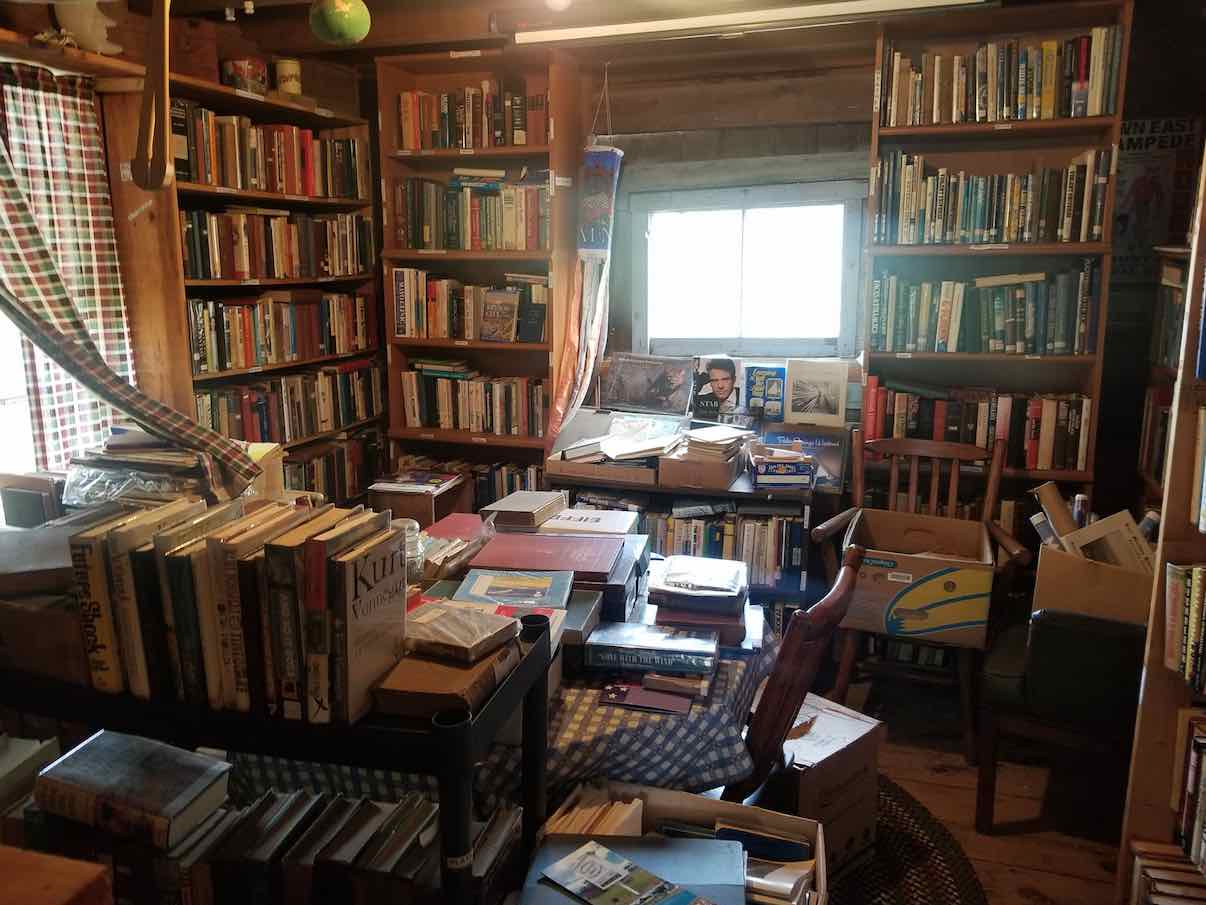

In the following photo collection we will show the owner of a used bookstore and the stacks of books that he meticulously cares for. There a photos featuring various objects around town that have sold in one store and displayed in another demonstrating the intricate network thriving within the reuse businesses of Machias. There are photos of a “free for the taking” area that displays the numerous and unique items that people leave and donate, along with various signs showing what reuse means. There are photos that bring together the care that a seller on the flea market has for his objects and the joy he got in sharing his story with us. Together these images suggest care and social networks can be found in all different forms of reuse in Machias.

News Media

Prior to heading out into the field, our team researched existing media related to the reuse economy in Machias. Below are the article links (through the Fogler Library at the University of Maine) to fascinating and relevant news coverage in and around Machias, Maine. The articles explain the kidnapping and rescue of a mechanical gorilla that was a prominent figure that captured the heart of the town and many others at the local flea markets. His news coverage exemplifies the care the people have for some of the objects and the lengths they will go to to protect them. Other articles demonstrate the ways in which reuse businesses provide support for the community. There are numerous examples of how thrift stores are more than just a store, they are a community service caring for the local people. Finally, some articles conflict with our findings – suggesting that reuse is complex and multifaceted. There are stories that articulate the conflicts and clashes within the local reuse sector. These stories, along with our own work, provide a glimpse into the complicated sociocultural dimensions of reuse in Machias.

- Blueberry festival adds flea market to events

- No decision on changes to machias dike

- Machias downtown committee nixes dike vendor fee

- Machias Food Pantry to hold yard sale benefit

- Gorilla thief’s ally makes call for mercy

- Homegrown: Downeast Dealer card game | The Maine-based card game is based on a fictional yard sale

- 8-year-old given guitar to help soothe injury Ailing man’s gift helps reassure boy at hospital

- More than a store – a community service

- Yard sale to benefit historic 1-room schoolhouse: [All Edition]

- Gorilla in police custody YouTube video aided recovery of robot in Vt.

- Mainer to head to Vt. to retrieve gorilla stolen in E. Machias

Research Findings

We find that participation in Machias’s reuse economies is characterized by an ethic of care and supported by strong social networks amongst reuse sellers. Building on existing research which highlights the role of care and community in reuse networks (Albinsson & Yasanthi Perera, 2012), we suggest that even when reuse occurs in communities facing substantial economic struggles, it is never just about a need to survive. Instead, motivations and meanings behind reuse participation are diverse (Berry et al., 2019), and those who donate, sell, purchase, and find used things are all involved in creating networks of support and care.

Care for People & the Community

Many of our participants framed their work as an act of care for people and for the community. A local seller of used furniture described her work as offering two kinds of services to people: a way to get rid of things they no longer needed (and receive money for them), and a way for people to access low-cost used items. Many of our participants commented that they “weren’t in it for the money” and that instead they saw their work as helpful to others, or to the community as a whole. A local bookseller expressed his hopes that his shop would be a place for children to kindle a love of reading. He noted with great pleasure that last summer “every kid that came in with mom dad grandma or uncle…whomever….came into the [shop] and went out with a book, which was a very first ever” (Interview, 2019). He worries about children spending too much time on screens, and not experiencing the joy of reading a book they can hold in their hands. To him, as to many of the people we spoke with, care for his customers came before making a sale. Similarly, the owner of a bookstore and cafe noted that her goal was to create a gathering space where like-minded people could come together. While she hoped that people would purchase the books and antiques she has for sale, she sees her work as contributing to the social fabric of Machias. Some sites of reuse operate on a free model, as with an area transfer station that hosts a “swap shop” where people can leave or take items at no cost. One of the regular volunteers in this store commented that the shop is “wonderful” for the area because “everything’s free. And a lot of people can’t afford a lot of the stuff. A lot of kids want name brand. They can come here and get it for nothing” (Interview, 2019). The volunteer labor that powers this shop not only reduces waste, it also serves as a community meeting place and a much-needed source of material goods to those who want or need them.

Care for Objects

In a bookstore located inside a converted garage, a bookseller carefully smooths down the curled covers of his softcover books. He describes the conditions books thrive in (cool, dry), as he explains how his unheated business feels during the winter months. The books are happy and the people make it through. We stand on the dike in Machias speaking to a seller of antiques and collectibles at an informal, open-air flea market. As he tells us about his health troubles and his recent economic struggles, he also describes the objects he sells with great affection: an old buoy from an historic Machias restaurant, “an oxen-poker…for poking oxen,” and World War II memorabilia that he’ll sell at cost to someone who will value it. An antique store owner recites the origins of her furniture like the lineage of a great family. A seamstress tells us about customers who have their favorite jeans repaired over and over again because they can’t stand to let them go. These business owners and their customers are not simply buyers and sellers – they are, in many ways, stewards of objects with great emotional value. Even items that are not worth much money – old children’s books, small knick knacks – may be full of emotional value. The sellers display great care for objects – a care which for some can be a burden, and for others a great responsibility. We see this ethic of care for objects in the academic literature, as well, where objects are imbued with a sense of self from their previous owners (Belk, 1988). In Machias, objects are not just items that can be used to “get by,” but instead are full of emotion, history, and meaning.

Supportive Networks

A flea market vendor has been setting up a table on the Machias dike for years. Though suffering numerous heart attacks he still sets up on the dike – along with many others – because, in his words: “I get to talk to people. I get to be out in the fresh air when it’s nice” (Interview, 2019). Though the vendors on the dike are in competition with one another – sometimes even keeping customers away from one another’s booths – they still form a loose network that displays relations of care. After his recent health troubles, other vendors will “hang around, wait, make sure I’m okay” at the end of the day when he packs up his wares (Interview, 2019). We unearthed a network of caring; places that should have been in dire competition with one another were actually coming together, knowing that they were so few in numbers. An antique shop owner described being able to call up another store owner for help pricing items if she was unsure of the value. Other store owners recommended that customers visit different stores if they knew the store had what the customer needed. One business owner commented that “we all recommend one another to each other” because there aren’t many shops in the area and they can use the support. Still other networks are evidenced by the objects that move from place to place in the area. One business owner shops at a used furniture store to furnish their rooms with vintage items. At a local transfer station “swap shop” we found a community of volunteers more than willing to share their knowledge of the region’s thrift stores with us. These networks – informal as they are – connect used product retailers and their customers. They support the care for people and objects that we observed throughout our time in Machias, and seem to help the businesses get by when economic times are tough. Despite the reality of the current economy these reuse participants love what they do and hold a resonating care for their community and how they can help it.

Researcher Reflection: Brittany Woods

Coming into the field school with no field work experience, I was unsure as what to expect. Ethnography was more complex than I had imagined. I believed that people interested in an area went somewhere and wrote down what they saw. I had no idea how much paperwork was involved, how technical all aspects could be. I was unaware that people needed certification to do expert interviews, or that the interviewees needed to sign releases. In our field experience, I saw how quick people were to trust someone. We asked people to talk to us and we were given life stories before we could even state who we were or what our intention was. I found it compelling that these people opened up so willingly until they saw the legal paperwork, it was like a switch went off and it became something legal instead of a conversation. I began to wonder how much the legal side affected the story that we were being told. I learned that people believe what they are saying, but may skew it to what we are looking for or what they want to portray. I learned to understand that everyone has their own truth and, though it may contradict something else, both are true to the people that are sharing it. I discovered my own strength in the field; adaptability. I am strong at being able to adapt to situations and keep going. I found my flaws as well; I am a quiet and calm individual which meant that people were not as keen to open up to me as my other companions because they could sense the wall that I put up when meeting people, which in turn makes them guarded as well. Taking descriptive and useful field notes is a skill that I am still working on, I found that I was writing down information I did not need, or was not relevant. I need to hone those skills and learn to open up to the person that I am interviewing.

Researcher Reflection: Zahira Roldan

As the date approached to starting May term, I was wicked skeptical and nervous entering into a course that was half lecture/half research. I had stepped out of my comfort zone and explored a new area that is now apart of my skills and has broaden my thoughts with respect to the reuse topic that was studied in the Ethnography Field research. As any other class, I expected all lecture and no outdoor skills but it changed my whole perspective and when I first step foot into the first lecture day, I didn’t speak but felt a very welcoming environment from our professor Cindy Isenhour, as well as from the other researchers. As well the amount of time we had to put into this course, from certifications to reflections and our field notes that prepared us for our next adventure. When we approached to the field location that we chose, I didn’t take into consideration at how professional and difficult conducting sociocultural research in an area that doesn’t have much. Without a doubt, I have completely turned embraced a side that I did not have but created over the weeks leading up to our experience. I was pleased to be able to be apart of a research topic that was helpful for the community and how open many of the participants were and especially those that felt a sense of accomplishment being apart of such a great topic. Within minutes of arriving, we felt the energy of welcoming arms as well as stories from far and near. I had learned so much from the field notes that I had written and the conversations and interviews that we had with people and how each conversation had its own value to the topic we researched but nonetheless, each person we talked to had but good things to say and though we were a research team, they were skeptical to lead us “too deep into the water”. I had learned way more than I expected on this trip and especially with the skills that I have acquired in the Ethnography course.

Bibliography

Albinsson, Pia A., and B. Yasanthi Perera. 2012. “Alternative Marketplaces in the 21st Century: Building Community through Sharing Events.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 11 (4): 303–15. doi:10.1002/cb.1389.

Belk, Russell W. 1988. “Possessions and the Extended Self.” Journal of Consumer Research 15 (2): 139–68.

Berry, B, et al. 2019. Rummaging through the Attic of New England. Worldwide Waste: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2(1): 6, 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/wwwj.16

Frederik Larsen (2019) Valuation in action: Ethnography of an American thrift store, Business History, 61:1, 155-171, DOI: 10.1080/00076791.2017.1418330