Portland, ME

Introduction: "SO MUCH STUFF… SO MUCH WORK"

In southern Maine, where the tourist economy thrives and a coastal, urban vibe mixes with Maine’s long-standing traditions of thrift – a unique second hand economy has emerged. Our team could have spent weeks visiting all the antiques and vintage boutiques, community sharing initiatives, and consignment stores – but we learned a lot during our short time in the field.

In southern Maine, where the tourist economy thrives and a coastal, urban vibe mixes with Maine’s long-standing traditions of thrift – a unique second hand economy has emerged. Our team could have spent weeks visiting all the antiques and vintage boutiques, community sharing initiatives, and consignment stores – but we learned a lot during our short time in the field.

Peter grew up well enculturated in Maine’s culture of thrift – his first bike was from the dump but he’s new to ethnographic research. Cindy has been doing research about consumption and waste for a long time. She has strong ideas about the potential promises and pitfalls of reuse but has never led a field course. Suman, who is from Nepal, is learning about more than just Maine’s cultures of reuse. While he is new to US consumer culture and ethnographic research, he draws upon his experiences in community-based climate adaptation to think about the environmental and social benefits of reuse.

The were many themes that emerged throughout our time in southern Maine. However, based on our visit to the town of Buxton’s take it shop (affectionately referred to as the Buxton mall) and our observations at Goodwill of Northern New England’s “Buy by the Pound” shop, here we focus on the challenges associated with the sheer quantity of used goods generated in contemporary society and the imbalance that exists between the number of people that give used goods away (supply) and the number of people that buy them (demand).

But this approach is about much more than the economy. For the people that inhabit reuse economies – and the various social programs that depend on them – donated products that aren’t repairable or able to be resold carry a significant burden. The people that populate the second hand economy become responsible for their disassembly, repair or – despite their best efforts to salvage value – disposal. And yet we found significant value in the efforts of people throughout the reuse economy – the people who sort, clean, fold, photograph, list, market and resell goods to get them to the places and markets where they are more likely to be utilized. The research we present here suggests that this work is not trivial, but is most certainly undervalued

Literature Review

Between 1960 and 2010, solid waste generation in the US increased from just under 80 million metric tons to 227 million metric tons, an increase of more than 180% (EPA 2014). Fortuna and colleagues found that products in the waste stream “represent the main increase in absolute waste generation over this period with seventy percent of the total waste generated in the United States” (Fortuna et al 2016:2454). To reduce the amount of solid waste that is directly disposed in landfills, different countries, cities and regions have started to encourage the use of secondhand products and the extension of product lifetimes through repair – with the collaboration of multiple participants including the public, industry, reuse organizations, charities and policy practitioners (Stokes et al. 2014).

Together these organizations are making an effort to shift away from a linear economy to a more circular economy in order to attain the principle of sustainable consumption― “the consumption of goods and services that meet basic needs and quality of life without jeopardizing the needs of future generations” (Cooper 2008:52). This can be done by increasing the life span of the products, which could be done by increasing natural durability of the product during production and by encouraging people to maintain products through careful use, reuse and repair. “Durability is one of the most obvious strategies for reducing waste and increasing material productivity” (Cooper 2008:52). Buying a product made out of durable material may cost more initially, but results in savings over the long term.

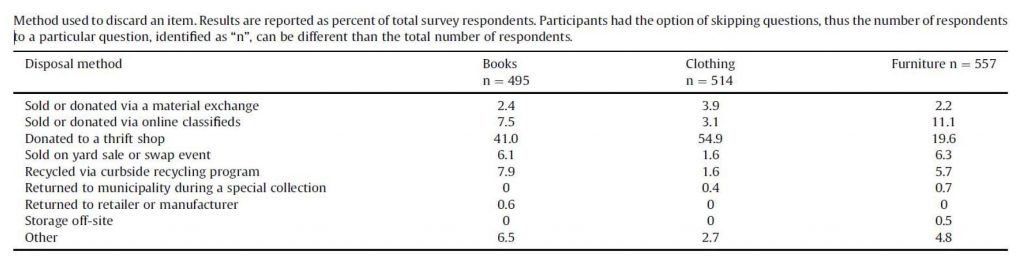

Despite significant efforts to encourage more circular economies with greater levels of reuse, several studies suggest that are barriers to participation. Fortuna and colleagues (2017), for example, found that people are more likely to donate used goods in reuse markets than they are to buy them, suggesting that demand for secondhand items is significantly lower than the supply. They reported that most discarded books (88%), clothing (88%) and furniture (77%) were identified as reusable; however, most of the people discarding them found that it was much more convenient to donate these reusable items than to invest the time and energy required to sell them (Table. 1).

Several studies have also documented recent increases in charitable donations. However, authors Gazley and Abner (2014) note that we have very little understanding of what happens with these items are used once they move out of donors’ hands (Gazley & Abner, 2014) and caution that many recipient organizations may not have the capacity to handle more donations. Moreover, they argue that “The burden of processing donated products might fall particularly hard on volunteer-driven organizations that depend on contingent labor” (2014:339). The donated gifts require intensive additional resources (essentially labor) to transport, store and process them. These activities are labor intensive and the need for large numbers of laborers to bridge the gap between supply and demand of these donated items is high, and is difficult to fulfill (Gazley & Abner, 2014; Whalen, Milios, & Nussholz, 2018). In this project we tried to understand the imbalance between demand and supply and the challenges associated with reuse markets.

Surplus Stuff

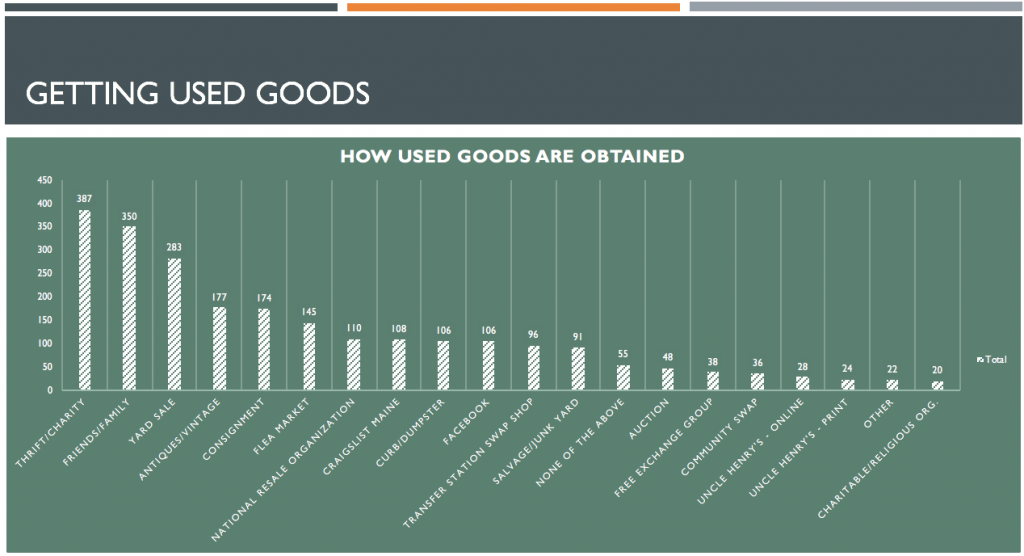

We talked to lots of folks, from managers at church-based thrift shops, cobblers, and transfer station operators to representatives from some of the region’s largest donation-based charities. One thing they consistently told us confirmed previous research findings – that there is a significant gap between the number of people who are trying to get rid of used goods and the number of people who are looking for them. The two graphs featured here – which are based on data gathered with a survey of approximately 600 Maine households (Isenhour & Berry, forthcoming) – illustrate that while many Mainers are participating in reuse markets, many more are getting rid of things and far fewer are in search of them.

The Buxton transfer station’s “Take it Shop” allows residents to drop of still usable goods they no longer want and need. Some bring things to leave behind and stay to browse. Some walk away with more than they brought. However, every few days the station manager and his crew have to clean out the shop because the volume coming in far exceeds what goes out. As Manager Greg Heffernan tells us here, by Saturday afternoons the place is often so full you can’t walk through it. This experience is also echoed by the manager of a religion-based charity shop who has to send bags of clothing away to be recycled by Salvation Army. Despite these challenges, folks like these two invest significant time, thought and labor – to bridge these gaps between supply and demand. As we hear, if you write your name on their swap chalkboard, Greg will give you a call if somebody drops off something you’re looking for.

Durability

These photos illustrate the products that people are not likely to throw away but would rather have them repaired or tuned up to extend the lifetime of the product. The first two images are from Portland Gear Hub, a non-profit interested in helping kids learn how to fix their own bikes. While not every bike is worth saving, they are able to strip them for parts and use what they can from the bike. The next two pictures are from The Yankee Cobbler in Bangor, Maine. Cobblers are not often people’s first thought when their shoes break down. But many people in Maine still come to the cobbler to extend the life of their shoes. The shoe and clothing markets are being flooded with cheap goods that often get thrown away. The cobbler is a great way to keep durable shoes in the market. The last two pictures are from Computer Solutions and Repair shop. As smartphones are released year after year, many perfectly good phones are going to be thrown away. These pictures illustrate how many phones that are still operational will soon need to be replaced because service providers will no longer support their older technology. In looking towards the future, we have to think about the products we are buying as an investment. Even though buying higher quality up front is more expensive, it will be cheaper in the long run.

Circulation

Research Findings

In today’s society, many people throw things out without giving them a second chance – a chance to be reused, repurposed, or redesigned into something great. Each week the garbage man comes, picks up the trash and we don’t have to think about it ever again. Large donation centers have also made it extremely easy and convenient to get rid of the things we no longer want or need. Reuse in Maine is alive and well, in part, due to the sheer volume of goods moving through both our new product and second hand markets. In our literature review we found that there are many reasons to repair and reuse: economic, environmental and social. We set out to learn more about what inspires people to participate, but also what prevents people from using things longer or buying things second hand.

We found that, much like any other economic system, reuse economies work according to the laws of supply and demand. But there is much more to it than a simple formula. Sure, most second hand goods (with exceptions for rare antiques and vintage goods) are cheaper than new products. This is largely because much of the supply comes from donations and the things people throw out – and there is a lot of it. The demand comes from people who want to buy second hand – for the thrill of the hunt or the cheaper price – but finding what you want, when you want it is tough. But what we found to be most surprising – was that there is a third factor, an important mediator that works to reduce the gap between supply and demand – time and labor. The labor it takes to sort through all the donations, to transport items from place to place, and the time that people take out of their day to do what is essentially unpaid or underpaid work. While it is true that many people enjoy searching for that long-lost treasure or the bargain in the bin, the hunt really loses its charm when you have to sort through tons of discarded materials (as our team observed many people doing at a large donation distribution center). What we as a team concluded through our interviews and observation was that while donations are great and there are significant economic, social and environmental benefits associated with reuse, there are also hidden costs. We saw that people are donating by the truck load to transfer stations, community yard sales, Goodwills, and thrift stores as a guilt-free means of disposal. Unfortunately, the time and money that goes into sorting and racking those donations are seriously undervalued. We have found that the rate at which people buy second hand is far lower than the rate at which they donate. While the people of Maine are no strangers to reusing something from a transfer station or yard sale, the work that it takes to get things from where they are donated to where they might be most useful is considerable and yet the costs of this hard work are often overlooked when we think about the costs associated with contemporary consumption patterns. In looking to the future, we may need to not only consider putting a greater emphasis on reuse as a way to stop flooding our waste stream with products that don’t last – but also to rethink how we value the hard work that goes into ensuring that goods with value are kept out of the waste stream.

We found that, much like any other economic system, reuse economies work according to the laws of supply and demand. But there is much more to it than a simple formula. Sure, most second hand goods (with exceptions for rare antiques and vintage goods) are cheaper than new products. This is largely because much of the supply comes from donations and the things people throw out – and there is a lot of it. The demand comes from people who want to buy second hand – for the thrill of the hunt or the cheaper price – but finding what you want, when you want it is tough. But what we found to be most surprising – was that there is a third factor, an important mediator that works to reduce the gap between supply and demand – time and labor. The labor it takes to sort through all the donations, to transport items from place to place, and the time that people take out of their day to do what is essentially unpaid or underpaid work. While it is true that many people enjoy searching for that long-lost treasure or the bargain in the bin, the hunt really loses its charm when you have to sort through tons of discarded materials (as our team observed many people doing at a large donation distribution center). What we as a team concluded through our interviews and observation was that while donations are great and there are significant economic, social and environmental benefits associated with reuse, there are also hidden costs. We saw that people are donating by the truck load to transfer stations, community yard sales, Goodwills, and thrift stores as a guilt-free means of disposal. Unfortunately, the time and money that goes into sorting and racking those donations are seriously undervalued. We have found that the rate at which people buy second hand is far lower than the rate at which they donate. While the people of Maine are no strangers to reusing something from a transfer station or yard sale, the work that it takes to get things from where they are donated to where they might be most useful is considerable and yet the costs of this hard work are often overlooked when we think about the costs associated with contemporary consumption patterns. In looking to the future, we may need to not only consider putting a greater emphasis on reuse as a way to stop flooding our waste stream with products that don’t last – but also to rethink how we value the hard work that goes into ensuring that goods with value are kept out of the waste stream.

Researcher Reflection: Peter Duda

This project has been an invaluable experience for me in putting my home state in a new light. Thinking about it like I have never thought of it before. I had always known that Mainers reused a lot of things. They participate heavily on curb side stuff that is free for the taking. This project allowed me to actually see to what extent mainers reuse, and in what forms they reuse the most. It also opened my eyes to just how much stuff we go through on a day to day basis. Literally millions of tons are being pushed into our waste stream without even considering if it still has value. This was my angle for the majority of the project, at what point do people say it is not worth investing the time and labor to reuse a product or material. I found the “point of no return” to be a subjective answer from everyone that we talked to, from transfer stations, thrift stores, and pawnshops. For some, its if the product would not be worth the money and labor to fix that would make them throw it away. For others, it would be if the product had too many holes, or stains, or tears. While the decision to throw something out versus reusing it is a subjective one, there is no doubt that if people considered reusing or repurposing more of their stuff our landfills would not be as overflowing as they are today. After this project I will not be getting 100% of my stuff from only reusable spots, but what it has made me do is consider living in a more conscious way with the stuff I have and the impact it has on the rest of my community

Researcher Reflection: Suman Acharya

I enrolled in the Digital Ethnography Field School with a primary aim of experiencing ethnographic methods in social science research. I was interested in learning some ethnographic methods of data collection like interviews, questionnaire survey, field/participant observation and about the use of digital technology in ethnographic research method. Moreover, I got a chance to learn about the procedure of reuse business, the trend of reuse business in Maine, different types of reuse businesses in Maine and the importance of reuse market in managing and reusing the secondhand products produced in every households. Within three weeks of the summer course, I got a chance to fulfill most of my aims of joining this course.

Some important aspects I learned and felt important in ethnographic method:

- Communicating with different persons at different areas like companies, governmental offices, organizations, market, industries and public people.

- Being clear with the aim of the study and developing clear research question based on or broad research topic.

- Way of doing interview, intercept and questionnaire survey, identifying the most suitable person that are suitable for doing interview and squeezing into the key element that we want to talk.

- Using different digital multimedia technologies like audio recorder, camera and iPad in ethnographic research methods. Moreover, producing a fine result in digital form (photo story, audio story and graphical representation from data collected).

- Research ethics (IRB, Consent form etc.) that are to be followed from writing proposal to the final research product.

- Learning about coding and using transcribing tools in data analysis was interesting and new.

- Broader knowledge on solid waste management practices done in Maine, essentially with reuse market.

- Learning about reuse as a strategy in climate change mitigation was really interesting.

- Production of alternative energy from the final waste that are supposed to dump in the landfills was new learning.

- Working in a team with mutual understanding and cooperation manner in new environment (USA) was best part of learning.

Important lessons for future field work

I am going to my preliminary field work of my graduate studies in a few days. So, the learning above I mentioned are important lessons for my field work. I will be doing participant observation and interview for my preliminary field work and further field works. I received good knowledge on these ethnographic methods that I will be using in my research. I will be using transcription tools like Trint and NVIVO and digital multimedia like audio recorder and phone for my research, which I clearly learned from this field school. Overall, this was an amazing learning that will have great implications for my future field work.

Bibliography

Cooper, T. (2008). Slower Consumption Reflections on Product Life Spans and the “Throwaway Society.” Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9(1–2), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1162/1088198054084671

EPA (2014) Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States Tables and Figures for 2012. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/2012_msw_fs.pdf (Washington DC, US).

Fortuna, L. M., & Diyamandoglu, V. (2017). Disposal and acquisition trends in second-hand products. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 2454–2462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.11.030

Gazley, B., & Abner, G. (2014). Evaluating a Product Donation Program: Challenges for Charitable Capacity: Evaluating a Product Donation Program. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21094

Stokes, K., Clarence, E., Anderson, L., & Rinne, A. (2014). Making Sense of the Collaborative Economy. NESTA & Collaborative Lab. http://www.collaboriamo.org/media/2014/10/making_sense_of_the_uk_collaborative_economy_14.pdf

Whalen, K. A., Milios, L., & Nussholz, J. (2018). Bridging the gap: Barriers and potential for scaling reuse practices in the Swedish ICT sector. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 135, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.07.029