UMaine leading development of new state-of-the-art tool for tracking PFAS nationwide

The emergence of toxic per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, in water supplies, farms and the environment is a growing problem nationwide. Despite many researchers and government agencies investigating these “forever chemicals,” there is no tool for combining all of their findings and providing a more comprehensive view of the problem.

University of Maine computer scientist Torsten Hahmann is spearheading the development of an interactive digital tool that will allow users to explore and analyze data on sites and sources of PFAS contamination throughout the U.S. This software will help investigators and the general public track existing PFAS hotspots, which in turn can help them identify where to test for new ones and better understand how they travel through the natural and manmade environment.

“There is a ton of data out there and plenty of people are testing, but nobody knows how it all fits together,” Hahmann says. “We are building connections among different pools of data.”

The National Science Foundation awarded $1.5 million for the project, one of 18 nationwide it recently funded with a combined $26.7 million through its Building the Prototype Open Knowledge Network (Proto-OKN) program.

Each project involves collaboration with a federal agency. Torsten’s team is partnering with the Environmental Protection Agency to develop its PFAS tracking tool, called the Safe Agricultural Products and Water Graph (SAWGraph).

“We’re really focused on getting a product out that the EPA can use for a long time,” Hahmann says.

PFAS have been used widely in industrial and consumer products such as nonstick pans, takeout food containers and firefighting foam since the 1940s for their resistance to grease, oil, water and heat. Current research suggests that exposure to high levels of certain PFAS may lead to adverse health outcomes, including immune system disorders, thyroid hormone disruption and cancer.

PFAS are referred to as “forever chemicals” because they tend to break down very slowly or not at all. They can bioaccumulate in plants, animals and people. They have been found in wastewater sewage that farmers in Maine previously used as fertilizer. In response to concerns surrounding PFAS, the state banned the sludge spreading on land in 2022.

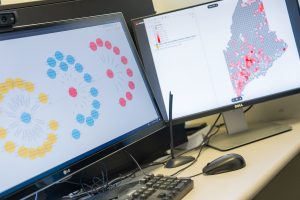

Like existing websites for tracking PFAS, the one powered by Hahmann’s SAWGraph will feature a map that displays contamination sites and are color-coded based on where and in what the PFAS have been found, including soil, surface or well water, farms, food, domestic or wild animals. It will also provide the same visuals and codifications for PFAS sources and areas where PFAS-containing wastewater sludge was used as fertilizer. A new feature provided by SAWGraph, however, is the ability to connect that data with potential sources, impacts to food and water, and transport mechanisms of PFAS.

SAWGraph users can then break down the information based on the category of contamination and location, from the state to the municipal level. New data from state and federal agencies will automatically be uploaded into the software.

“We’ve been talking with Maine and federal agencies to see what they would like to see, what technology could make things better so they don’t just have to use spreadsheets,” Hahmann says. “We can present multiple sets of data at once, which can help with rather complex queries about things people really want to know, rather than just show rows and columns of numbers.”

Hahmann and a few colleagues are already developing a prototype that includes only sites of contaminated soil and water in Maine, supported by seed funding from NASA’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) Research Infrastructure Development (RID) program that was awarded by the Maine Space Grant Consortium. The NSF funding allows his team to refine and expand the prototype.

With an abundance of data that users can organize based on their needs, Hahmann says the SAWGraph can help answer various questions about PFAS contamination. For example, they can look at data from all of the wells located downstream from a water source polluted by PFAS. They can see what counties that have undergone testing have the highest and lowest levels of PFAS contamination and prioritize further testing accordingly. Based on the location of pollution sites, they can even explore whether nearby food or water supplies are threatened by these “forever chemicals.”

Hahmann says the SAWGraph can also help determine what other data is needed to tackle the PFAS problem on a national scale. Additionally, it may help users identify any possible threats to their properties, and state and federal agencies determine where additional testing might be most urgent.

“There has already been significant testing done, but we only have so much testing capacity. It takes a lot of time and it’s expensive,” Hahmann says. “We can’t test everything.”

Other researchers involved in developing the SAWGraph include Onur Apul, UMaine assistant professor of environmental engineering; Ganga Hettiarachchi a professor of soil and environmental chemistry at Kansas State University; Pascal Hitzler, the Endowed Lloyd T. Smith Creativity in Engineering Chair of the Kansas State University Department of Computer Science; Hande Küçük McGinty, an assistant professor of computer science at Kansas State University; Hari Prasath Palani, a UMaine alum and associate research scientist at the Roux Institute at Northeastern University; Shirly Stephen, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California at Santa Barbara; and UMaine Ph.D. students Katrina Schweikert,David Kedrowski and Sonia Moavenzadeh.

Many UMaine researchers are working together on several PFAS research projects as part of the UMaine PFAS+ Initiative. Apul is science lead and a steering committee member for the university-wide initiative to focus on the emerging PFAS pollution crisis and its cascading environmental and societal impacts.

Contact: Marcus Wolf, 207.581.3721; marcus.wolf@maine.edu