Evan Warburton: A fun guy studying fungi

Evan Warburton is wild about mushrooms. He forages for edible mushrooms, grows oyster mushrooms in his apartment and researches how fungi interact with trees as an undergraduate researcher at the University of Maine. Inspired by the community of UMaine mycologists, Warburton is growing into a great researcher in his own right, studying the underground fungal networks that support forest ecosystems on Maine’s coastal islands.

During the pandemic, Warburton spent a lot of time walking around the woods at his childhood home in New Jersey, foraging for mushrooms and listening to podcasts. He was listening to an episode about famed mycologist Paul Stamets discussing the mycorrhizal network, or the network between trees and certain fungi that exchange essential soil nutrients for sugars to help keep the trees healthy and feed the fungi.

“The transfer of energy is interesting to me,” Warburton says. “Not all organisms eat like we do. Most fungi are decomposers. They secrete enzymes that break down their food, like if we were to barf up our stomach acid to break down our food and then eat that product. The aspects of biochemistry tied in through this metabolic activity and the ecological implications of looking at how this affects forest health made me want to do research on this.”

Then-sophomore Warburton reached out to UMaine mycologists to see if he could get involved with research. He eventually connected with Joyce Longcore, associate research professor at the School of Biology and Ecology, who has won the 2022 Distinguished Mycologist Award for her research about chytrid fungi.

Warburton learned valuable techniques in mycology from Longcore — and he greatly admired her work in the field — but her research wasn’t exactly what he wanted to study; he still had mycorrhizal fungi on his mind.

Longcore introduced Warburton to Peter Avis, a new mycologist in the UMaine community who would go on to be an adjunct instructor and is now director of CORE while continuing to conduct research. Avis was starting a project to look at mycorrhizal fungi on the coastal islands of Maine and asked if Warburton would be interested in joining. Warburton was “totally up for it.”

“His idea for the project was to go around to islands and sample them for their fungal communities based on island size, distance from mainland and human development on these islands,” Warburton says. “Maine has so many islands, so this is a very long term project.”

In August 2021, Avis and Warburton went to Roque Island to collect samples of soil, tree roots and seedlings to test which species of mycorrhizal fungi are present in the sites. They stayed for several days together in a cabin on the island as they conducted their field work.

“Evan [Warburton] was a fantastic colleague and partner,” Avis says. “He did everything I needed him to do and had tons of great questions. He was just a happy workmate even though it was buggy and rough conditions.”

The duo were able to collect samples from five more islands over the course of the next two years. Warburton also served as an intern at the Maine eDNA program, where he extracted DNA from water samples on Hurricane Island (another place where he was able to grab some soil for his and Avis’ mycorrhizal fungi project).

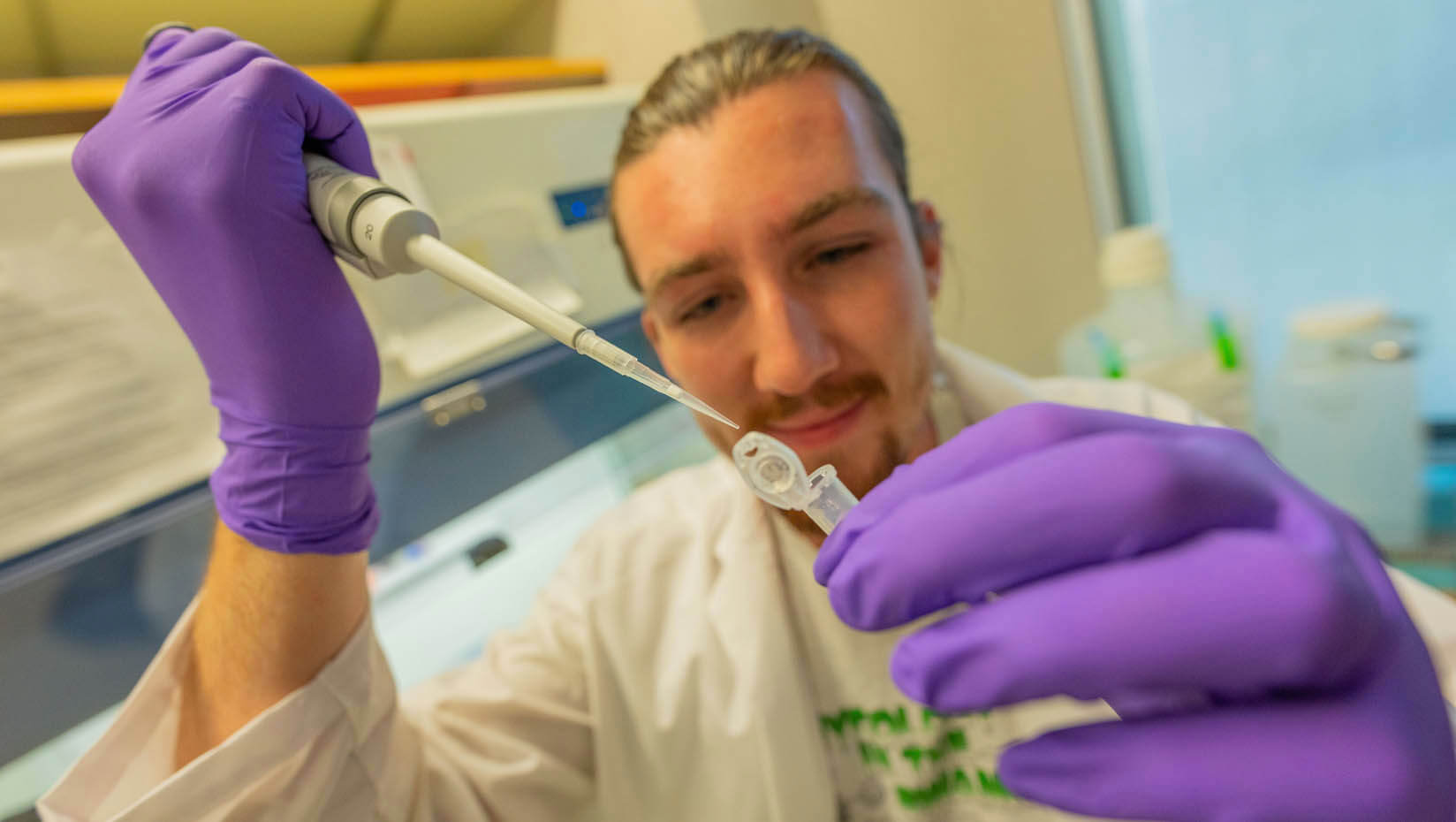

Warburton studied these samples in the lab throughout the rest of last school year and into this past semester, extracting DNA and conducting polymerase chain reactions to target what species they were seeing in the samples. Warburton says that already, they have found shared fungi species between the mature tree roots and the seedling roots in their samples, giving the impression that there is a potential connection between them. He has applied for a grant from the National Science Foundation to support his anticipated future graduate studies and to determine whether that connection means that the tree roots, seedlings and fungi are exchanging nutrients — or interacting in another way entirely.

Warburton is hoping to translate some of his current research into his capstone project. He is a biochemistry major with a minor in ecology and environment science, a combination that Avis says is unusual for a mycologist, but one of the things that makes Warburton special as a student researcher.

“He’s one of the first undergraduate researchers I’ve had that has pulled his interests from such broad fields together,” Avis says. “His training from biochemistry has influenced how he understands this complex phenomenon of mycorrhizal associations. He’s one of the students that has taken the lessons he learned in classes and can see them really clearly and is excited to apply those to the research that’s right in front of him. That’s pretty cool.”

Even though the mycorrhizal fungi research project is far from over, Warburton sees potential for how it could be used in the future.

“I want to find a way to apply what I’m finding out to forestry practices,” Warburton says. “If you leave certain trees that don’t have as much value in the lumbering business, mycorrhizal fungi can thrive.”

Warburton hopes to go to graduate school and continue researching the wonderful world of fungi. He has some experience presenting research already. This past summer, Avis was not able to present at the Mycological Society of America conference in Gainesville, Florida, about the research that he and Warburton had been working on. Warburton stepped up to the plate as UMaine’s sole representative to the prestigious conference and had the opportunity to present what they had found so far.

“I wasn’t expecting to talk a lot, but once the poster sessions started, I didn’t stop talking the entire time,” Warburton says. “It was a great experience. What was really cool was when we had the awards ceremony and they started listing off winners, the biggest award went to Joyce Longcore, and then a couple other awards were given to other mycologists who were UMaine alumni. I was like, ‘This is really cool that I’m here. Maybe I’ll get an award one day.’”

Contact: Sam Schipani, samantha.schipani@maine.edu