Lown legacy preserved with specialty U.S. Mint coin

Starting in 2019, the U.S. Mint began issuing four specialty coins per year, one for each state, in celebration of U.S. innovation for the American Innovation $1 Coin program. By 2032, leaders of all 50 states, the District of Columbia and the five U.S. territories will have chosen an innovator or innovation to represent their state or territory. This year, Maine celebrates University of Maine alumnus Bernard Lown as its most notable innovator.

Gov. Janet Mills nominated Lown, an immigrant from Lithuania who moved to Maine in 1935 to escape religious and political persecution and who committed his life to serving humanity through science and technology. Lown’s uncle owned a shoe company in Auburn, Maine with factories located about an hour north, where his father would earn a living and his family would find comfort in the area’s Jewish community.

Although he didn’t speak English when he arrived in Maine at the age of 14, Lown went on to graduate from Lewiston High School, the University of Maine and Johns Hopkins University. Less than two decades into his career as a cardiologist and research scientist, he developed a new method to correct abnormal heart arrhythmias, a leading and sudden cause of death.

Lown’s coin, which will be released on Thursday, May 16, depicts him using a direct current defibrillator, as it would have looked in 1962. His hands are symmetrically positioned on either side of a chest, holding handles that connect to what looks like a technologically advanced filing cabinet.

Electric currents were already being used on hearts that had stopped beating, but the procedure proved mostly unsuccessful. Lown discovered he could shock a beating heart without killing the patient. His method was first refuted by his colleagues, but he remained persistent and learned how to save his patients from a once incurable illness.

His invention of the direct current defibrillator, or cardioverter, wasn’t the only controversial issue he faced as a socially minded physician. During the Cold War, he worked with doctors in the U.S. and throughout the world to prevent nuclear warfare.

Around the same time he discovered the cardioverter, Lown founded Physicians for Social Responsibility. In 1962, the group published a thoroughly researched paper in The New England Journal of Medicine that depicted how people’s lives would change if a nuclear bomb exploded over Boston, where he was teaching and researching at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

He continued to advocate against nuclear arms and was later awarded the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize along with Soviet cardiologist Yevgeny (Eugene) Chazov. Together, they founded International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. By 1985, over 100,000 people spanning 41 countries had joined the group.

Active in the home

His children, Anne, Fred and Naomi Lown, knew from an early age that their father had a profound impact on the world. His social conviction moved through their home with sounds of symphonies and the aroma of their mother’s meals. They felt his passion in the air, through the books they shared and the ones he shared with them.

“He’s with me every day,” said Naomi Lown. “I just finished reading a book, one I want to share with dad. I feel the loss of those conversations and his insights, especially when the world is in such a disastrous place. He was an eternal optimist.”

As a teenager, she would wake up annoyed on Saturday mornings because of the full-volume opera music surging into the room where she slept. Now, her memories surface with a grin and an appreciation for his daily teachings in culture. The three children remember how their father led discussions in the dining room over their mother’s prepared meals. Some evenings, just the five of them sat at the table. Other times, physicians, researchers, friends or their father’s patients would join. The children recalled when one patient — a man whose name they still remember — stayed in their home for weeks while their father evaluated him.

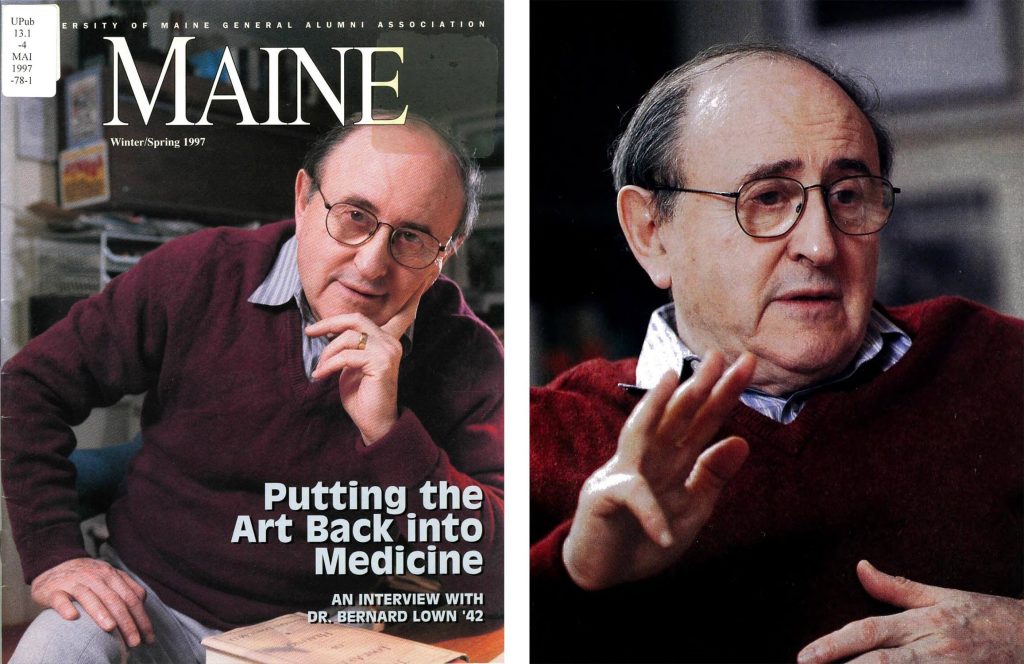

Bernard Lown held the firm belief that medicine and healing are beyond science. He practiced and taught that to truly care for a patient was to understand and know them as a person, not an illness. While teaching in a fellowship program, he gave his fellows a list of readings that he said would help them connect with their patients.

Anne Lown said she believes coming of age during the Holocaust largely contributed to her father’s belief system. Racism also persisted in the U.S. during his upbringing. While at Johns Hopkins, which at the time had a quota for admitting Jewish students, Lown undermined the segregation of blood from white and Black donors at a blood bank where he worked. It was a first of many actions he would take as an internationally leading social justice and peace activist.

His intellectual curiosity didn’t start when his family relocated to Maine, but the experiences he gained once he arrived further informed his interests in social activism and culture — namely his admittance to the UMaine Honors Program, now the Honors College, in 1938.

“He felt that the University of Maine really changed his life and gave him an opportunity to think deeply about the world and about intellectual issues,” said Anne Lown. “He got very excited about science when he was there, and that set him on the path to becoming a physician.”

Naomi Lown said many colleagues asked him about his undergraduate education at UMaine and why he didn’t attend an Ivy League university. He described the Honors Program to them, she said, like it was the University of Oxford, but in Maine.

Even though it’s not their primary state of residence, the Lown family has remained connected to Maine. They visit a summer home, and the Peace Bridge between Lewiston and Auburn bears Bernard Lown’s name.

“I think that people in Lewiston were inspired by his story,” said Anne Lown. “Every day when people drive across the Peace Bridge, I hope they’re thinking about him.”

More than medicine

Bernard Lown was chosen to represent Maine on the coin because of his invention of the direct current defibrillator, but his impact extends beyond the medical breakthrough.

He could have patented it, Naomi Lown said, but he didn’t want to gain wealth from the discovery. He wanted the technology as easy to access as possible — similar to his initiative in founding SatelLife USA, a nonprofit organization that launched a communications satellite in 1988 to connect doctors worldwide with the medical knowledge base in the U.S.

He was always concerned with the state of the world, Anne Lown said. When he started to think about the issue of sudden death, he became interested in the development of the defibrillator.

“As he was thinking about that, it occurred to him — as it occurred probably to the rest of the world in the middle of the Cuban missile crisis — that we all were facing sudden death,” she said. “My father referred to the final epidemic as nuclear war. As he was trying to work and save individual lives, he had a concern about a much larger issue of the world.”

Anne Lown, slightly older than her sister, grew up at the height of the Cold War. She remembers the terror of nuclear weapons and the nightmares that came with it. Her father taught her that by being a social activist, she could direct her feelings of fear for resolution.

She and Naomi Lown stuffed envelope mailers for their father, and they were privy to the many meetings held in their house for their father’s first group, Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR).

“I think he had a lot of fear, no doubt, because he was driven to try to find a solution for this and the madness that was going on with the escalation of nuclear arms,” said Naomi Lown.

The paper he worked on with PSR disproved the belief that people would survive a nuclear war with the right bomb shelters. It showed “that the living would envy the dead,” said Anne Lown. “That there would not be a world left to live in.”

Bernard Lown died in 2021 at the age of 99, less than two years after the death of his wife of over 70 years, Louise Lown. He was a devoted social activist, physician and educator, finding new ways to share knowledge at the age of 87 by starting the Lown Scholars Program at the Harvard School of Public Health. A year earlier, he gave up his clinical practice.

Since 1988, the UMaine Alumni Association has named 22 Bernard Lown Humanitarian Award recipients. It recognizes graduates dedicated to social service who have made an impact regionally, nationally or internationally.

The Lown Institute continues to work translating Lown’s vision for the world into advocacy for public health policy.

In addition to personal interviews and archived texts from the University of Maine, information for this story was pulled from Lown’s New York Times obituary and the U.S. Mint.

Contact: Ashley Yates; ashley.depew@maine.edu