The art of collaboration in natural resource management

Atlantic salmon are in trouble. Can effective collaboration help restore this iconic species? UMaine graduate student Melissa Flye researches how people and agencies work together and communicate in salmon restoration efforts.

June 2020

By the time Melissa Flye began a master’s degree in wildlife ecology at UMaine in 2017, the number of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) returning to New England rivers had dropped from historic levels in the hundreds of thousands more than two centuries ago to fewer than 1,500 fish annually.

After growing up in Maine and graduating in 2013 with a B.S. in wildlife ecology from UMaine, Melissa spent a few years working in natural resource management agencies and with consultants, gaining real-world experience. She had a strong background in biology and ecology, and knew she wanted to stay in Maine and continue working in natural resource management. But she also saw that efforts to manage some species were not as effective as they could be, despite the hard work, expertise and dedication of many people.

“Our issues aren’t really with managing fish,” she realized. “Biologically, we have a pretty strong understanding of what species need and in many cases we know what adjustments would result in higher population numbers. But often the real barriers to taking the actions that we know scientifically would be beneficial, involve people and how they work together.”

She decided she wanted to explore the human side of natural resource management, which hadn’t been part of her undergraduate curriculum. This led her to pursue her master’s degree at UMaine with Carly Sponarski, an assistant professor of wildlife, fisheries, and conservation biology and leader of the Human Dimensions of Wildlife Lab.

Carly came to UMaine in 2016, bringing with her a background that combined both the social and ecological aspects of natural resource management—not just how ecosystems and species function and interact, but also how people are directly and indirectly involved. Through her faculty mentor, Aram Calhoun, she connected early on with David Hart, Mitchell Center director, and found a natural fit with the center’s focus on work that is interdisciplinary, oriented to solutions, and purposefully engaged with stakeholders.

After attending one Mitchell Center talk, Carly had a “water cooler chat” with Joe Zydlewski and Bridie McGreavy, UMaine faculty members who are connected with the Mitchell Center. Joe is assistant unit leader at the United States Geological Survey, Maine Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and professor of fisheries science. Bridie is a Mitchell Center faculty fellow and assistant professor of communication and journalism. They discussed how natural resource management tends to focus on the biological aspects of problems, yet these efforts often require effective collaboration among agencies and organizations—collaboration among people. While expertise in the natural sciences is crucial for management, social science expertise is also needed to understand how people and organizations communicate, how goals are set, and how decisions are made.

“Biologically, we have a pretty strong understanding of what species need and in many cases we know what adjustments would result in higher population numbers. But often the real barriers to taking the actions that we know scientifically would be beneficial, involve people and how they work together.”

–Melissa Flye

Carly, Joe, and Bridie applied for a Mitchell Center seed grant in 2017 to examine the social factors that influence natural resource management. The purpose of this grant program is to help interdisciplinary research teams initiate solutions-driven collaborations with external partners. They chose to focus on Atlantic salmon because of the importance of this species in Maine, especially for Maine’s tribes. They received funding for a one-year project to evaluate the system used to manage Atlantic salmon in Maine and identify ways to improve its effectiveness.

To carry out this research, they needed a student with, in Carly’s words, “understanding of the ecology of fish in Maine along with a real zest and interest in the social aspects of species management,” and they found that student in Melissa Flye.

Atlantic salmon were once found in North American waters from Long Island Sound in the United States to Ungava Bay in northeastern Canada. The relationship between native people and Atlantic salmon goes back 10,000 years or more, but it was not until the early 1800s that salmon populations began to decline, as logging and other industries took root in Maine. Due to overfishing, pollution, dams, degraded habitat and climate change, their overall numbers have decreased dramatically in the past 200 years. Today Maine is home to the last remaining population of wild Atlantic salmon in the United States.

Attempts to manage Atlantic salmon have gone through many iterations. In Maine, a Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) was in place from 1980 to 2005, and was an early attempt at “collaborative governance,” where partners such as state and federal agencies and other organizations work together to help salmon numbers rebound.

Despite this effort, numbers of Atlantic salmon had declined so much that they were listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2000. Listing as an endangered species meant that collaboration among federal and state agencies and Maine Indian tribes was not only important, but also legally required. The Atlantic Salmon Recovery Framework (ASRF) was put in place in 2011 to enable better collaborative management under the ESA. It was comprised of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (US FWS), the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR), and the Penobscot Indian Nation (PIN).

Most participants in the ASRF were experts in biology, but none had training or experience in researching or understanding how people and organizations communicate and work together.

In concept, the ASRF was “a really good idea, all the pieces were in place,” says Dan Kircheis, Penobscot Bay Salmon Recovery Coordinator at NOAA. But in practice, ASRF partners recognized that the framework was not working in key ways, and that their collaborative management was not as effective as it needed to be to reverse the continuing decline in salmon numbers. They were ready to take a deeper look and be honest about how well the framework was working.

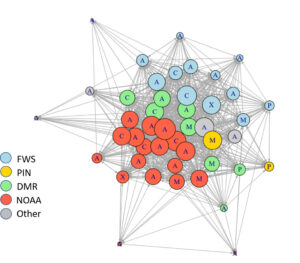

Under the guidance of Carly, Joe, and Bridie, Melissa Flye embarked on a case study of the ASRF to get a clearer picture of communication within the framework, and the experiences, views, and concerns of framework participants. She used Communication Network Analysis, a tool that generates data on the communication relationships in a group and creates a map to visually represent communication patterns. She also conducted detailed interviews to uncover people’s perceptions and experiences of the framework.

Her research findings showed that there was a lot of communication in the ASRF, which was a positive sign. But much of the communication was within partner agencies rather than among agencies. Participants were not clear on the framework’s goals or how decisions were made. Trust between agencies, participants, and leaders had eroded, and there was confusion about leadership.

In interviews with ASRF participants, Melissa heard things like:

“The management board has no set decision making process. It’s not by majority. It’s not by consensus. We don’t know how we make decisions.”

“…we never discuss our priorities, and how they might change over time.”

“I think one of the most difficult parts of it that people have trouble grasping are what decisions need to fall under the framework’s decision-making process versus their own agency decision making process. I think that needs to be clarified.”

At an October 2018 meeting at Schoodic Institute that became a turning point in the assessment and re-making of the ASRF, Melissa reported back what participants had shared in interviews, as well as data on how communication happened in the framework. “She had a completely unbiased perspective,” notes Dan Kircheis, and her work was “just exactly what we needed” to help clarify what the problems were, and guide the development of a new collaborative governance structure.

A new beginning

By the end of 2019, ASRF participants had created a new governance structure informed by the data and reporting from Melissa’s research. The new plan, the Gulf of Maine Distinct Population Collaborative Management Structure (CMS), was released in early 2020.

The CMS was launched as a one-year pilot to allow for ongoing learning, review, and adaptation, with regular reporting and opportunities for input included along the way. The first annual reports were done in May 2020, and the first public meeting was held online on May 28. Evaluation of the new structure is slated for the end of 2020.

The changes incorporated in the CMS include shifts in how management teams are structured, work is organized, participants communicate and information is shared.

For example, the ASRF was organized into “Action Teams,” each with a focus area such as marine and estuarine environments. But several partner agencies focus their work by geographic area, and this created confusion. Under the CMS, Salmon Habitat Recovery Units (SHRUs), organized geographically, replaced action teams. This approach aligns better with how participating agencies work.

Another problem with the ASRF was that there was not enough feedback between decision-makers—leaders and managers—and staff on the ground. An Implementation Team was added, embedded within the main decision-making body, to better connect leaders with SHRUs and staff working on the ground.

Sean Ledwin, director of the Sea-Run Fisheries and Habitat Division at DMR, says that the new governance structure has also allowed more room and openness for innovation in the efforts to protect and restore Atlantic salmon. Under the ASRF it was “a heavy lift” to get new projects off the ground, and the CMS is “letting a lot of new ideas come forward, which is really needed.” Now, he says there is increased energy in their efforts, and more of a sense of aiding and supporting innovation.

Can effective collaboration make a difference in the management, and recovery, of species?

The CMS is not a silver bullet, and Atlantic salmon populations remain dangerously low, despite continued efforts to augment their numbers with fish from hatcheries.

Some of the challenges faced by salmon have eased in recent years, from improving water quality to the removal of some dams that obstruct their passage as they return to Maine rivers to spawn. Other challenges, such as those posed by climate change, are making it more and more difficult for salmon to survive and thrive.

If we think of a ‘recipe’ for successfully managing wildlife species in the face of adversity, and for even having a chance to help threatened or endangered species recover, effective collaboration may be one of the key ingredients. The research conducted by Melissa Flye, with the honesty and courage of ASRF partners in assessing how their collaboration could be more effective, indicates that the ways that people and organizations work together, make decisions, and communicate must be studied and improved along with ecological functioning.

“Identifying effective strategies for collaboration can potentially benefit a wide range of efforts to protect or restore species and ecosystems at a variety of scales,” Carly says. “This project is a great example of the way the Mitchell Center helps bring together expertise in the natural and social sciences to solve real-world problems.”