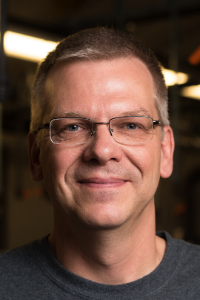

Meet Maine-eDNA: Markus Frederich, Professor of Marine Sciences, UNE

Discovering how things work has been one of Dr. Markus Frederich’s favorite activities since he was a child, so it’s no surprise that his research is based on physiology: the branch of biology that deals with the functions and parts of living organisms, such as animals, and how they work. Frederich is a Professor of Marine Sciences at the University of New England, where he has worked for 17 years. He’s also a researcher on the new Maine Environmental DNA (Maine-eDNA) program, a five-year initiative funded by a $20 million-dollar grant awarded by NSF EPSCoR.

Frederich has been specifically researching invertebrates and crustaceans, looking at temperature and stress physiology. His key interest, involving Maine-eDNA, is invasive species (such as Green Crabs or Asian Shore Crabs) that have been encroaching on Maine’s rapidly warming coastline.

Another piece of the puzzle is how to deal with these species, or how to potentially create an alternate industry that could not only remove a bulk of the invasive population, but also monetize it.

“I always use the example of Rock Crabs, which were invasive to Iceland. But now they’re an established fishery there,” Frederich explained. “However, there are also lots of invasive species that no one is interested in eating, and that can make the situation much more difficult. If we can open up a new business model, that’s great, but once a new species is established here, we need to find some way to live with them.”

The first step? Identifying which invasive species have already made the Gulf of Maine their home, and which may be on their way.

“Animals take advantage of the abilities they have in order to find or create optimal living situations,” Frederich said. “We can’t blame them for doing what they’re good at. My job is to find them and to try and understand what mechanisms allow these species to be so successful.”

Frederich aims to utilize new eDNA technology in order to develop specific protocols for detecting invasive species as they move into the Gulf of Maine. With traditional, physical collection and monitoring methods, scientists are limited to a certain, relatively small set of data. However, eDNA sampling, which is based on collecting information through water samples, allows researchers like Frederich to “cast a much wider net” without disturbing the collection environment or the other species who call it home.

Once the research team is able to establish these protocols, they can be used to detect just how serious of an issue certain invasive species have become, and potentially help predict which new invasive species Mainers may have to deal with in the future.

Frederich’s favorite aspect of the Maine-eDNA program thus far is working with students. He is currently acting as a Ph.D. advisor for Emily Pierce.

“I’m excited to train the next generation of scientists,” Frederich explains. “That’s what really makes my day.”