Maine-eDNA: Expanding research capacity in the state of Maine

With a new Track-1 grant from the National Science Foundation, comes new funding, new faculty and new research. Maine EPSCoR’s newest Track-1 Grant, titled Molecule to Ecosystem: Environmental DNA as a Nexus for Coastal Ecosystem Sustainability for Maine (ME-eDNA), is bringing environmental DNA research to the pine tree state, and positioning Maine as a national leader for understanding eDNA.

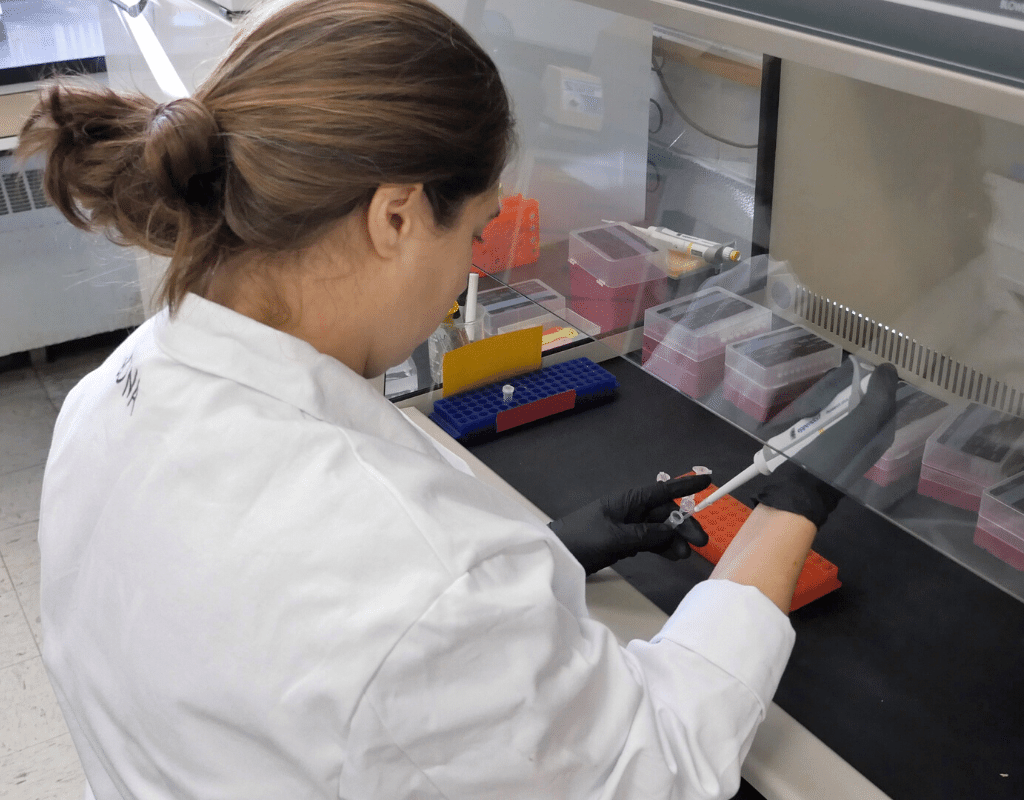

Geneva York currently runs the University of Maine’s new eDNA core facility, which just received two new laboratory instruments to advance eDNA research. The new machines specialize in analyzing larger than normal samples of water and identifying hundreds or even thousands of different species by sequencing their DNA. One of the new machines, a Digital Droplet PCR, allows researchers to test for specific DNA strands and produce extremely accurate counts of a target species within a body of water.

“As far as expanding research, we are on target for substantial expansion with the new equipment we bought off this grant and using this money to increase expertise and capacity for eDNA research in the state of Maine,” says York.

The core facility is key for eDNA research, but also provides a public service accessible to NGOs, conservation organizations, or even concerned citizens. Organizations send water samples to the lab, where the new technologies combined with Yorks’ expertise provide key understandings. York is currently working on 11 different collaborations with organizations around the state and across the nation.

For example, the Maine Department of Transportation (DOT) asked York at the core facility to use eDNA to identify key passages for atlantic salmon, so they can make informed decisions for where they build roads and culverts and avoid damaging migration routes of the salmon.

“We work with a lot of groups that are concerned with the conservation of race species or detection of invasive species,” says York. “The eDNA techniques we utilize are not invasive, so we can detect animals without actually interfering with their normal activity and without damaging them.”

The new eDNA core facility at UMaine positions the university and the state to become a national leader in eDNA technology. The collaborations that York has fostered in such a short period of time point to the rapidly expanding eDNA needs for conservation and development efforts.

“If we can become a leader in this technology, that will bring in a lot more research to the state and move a lot of conservation forward,” says York. “We want to make [the eDNA technology] more accessible so that more people will understand its utility and trust its results.”