Geosensor Networks Lab at the University of Maine Making Strides for Maine Agriculture

Over the years, the University of Maine School of Computing and Information Science (SCIS) has become a major player in the fields of computer science and spatial informatics. Through dozens of published papers, conference presentations, books, research projects, and major grants, UMaine has established itself as a pivotal player in academia around the world. The Geosensor Networks Lab, coordinated by Professor Silvia Nittel, seeks to take some of these advancements in academia and create real-world applications that can help the people of Maine.

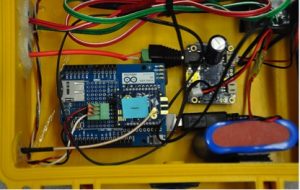

The Geosensor Lab specializes in just that; geosensor networks, which are networks of sensors placed in and on the earth to measure natural phenomena. These sensors can be used to record seismic activity, soil moisture, pH, temperature, and just about any other property of soil and air that you can think of. After several months of research and development, Dr. Nittel and graduate students in the Geosensor Networks Lab created a sensor to measure soil moisture tension and temperature, both of which are important to know in an agricultural setting. The sensor works by measuring the soil moisture tension and temperature at regular intervals, which it then encoded by an Arduino processor, very similar to the processor that you have in your cell phone. The sensors are powered by solar panels and use radios to wirelessly send the data to a “Raspberry Pi” minicomputer in another location in the field for further encoding, data storage and connection to the Internet. While the newly created sensor network configuration works in theory, it was still untested in practice. The researchers looked to the most logical place; the Maine blueberry industry.

There is no mistaking that Maine is a powerhouse for low-bush blueberry production; not only is does it account for 10% of the world’s blueberry production, but the state is actually the world’s largest producer of the fruit. This comes from a deep-rooted heritage in Downeast and Coastal Maine, where blueberry cultivation was first carried out thousands of years ago by Native Americans and continues today in large-scale agricultural operations. With over 44,000 acres of blueberries providing thousands of jobs to Mainers, the researchers at the Geosensor Networks Lab saw not only an opportunity to test cutting-edge techniques, but to help the Maine economy. Through a grant from the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, the lab was able to make this work possible.

To do this, the lab partnered with Cherryfield Foods to monitor one of their fields in Washington County. The lab had two goals, which included testing the ability of their newly constructed sensor network, and to see if the data gathered by the network contributed to growing healthier and heavier blueberries consistently across an entire field. What they found were several valuable facts; not only was the data highly useful in optimizing water distribution, but the sensors worked reliably throughout the 2 month deployment and were able to communicate with the Raspberry pi computer from over a mile away.

Now that the summer is over, the lab is working hard to implement the lessons learned over the summer in the blueberry field. Currently, the lab is developing a “field model,” which will allow them to not only record moisture from the sensors in the ground, but to be able to use that data to calculate moisture in other parts of the field in order to understand the field as a whole. The applications of this work can take many forms, including better sensor arrays for seismic activities in California, optimizing data gathering techniques to measure climate change, or even measuring precipitation in Maine potato fields in order to anticipate where water should be delivered to help crop production. With all of these potential applications it is hard not to be excited about the work that is coming out of the Geosensor Networks Lab. What will they come up with next?