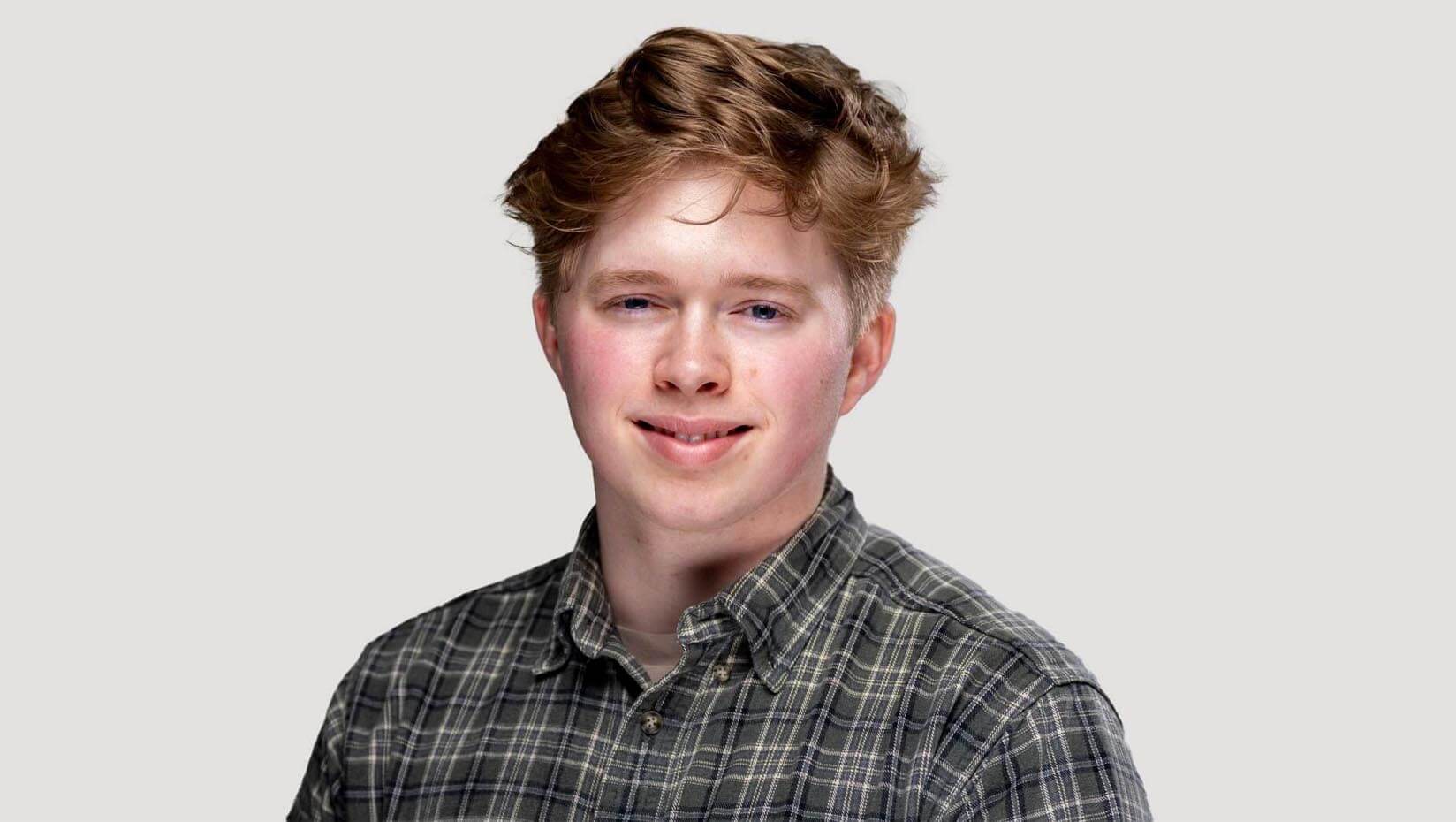

Dominic Needham: UMaine 2025 Co-Salutatorian

Dominic Needham of Veazie, Maine is a 2025 co-salutatorian. A microbiology major and member of the Honors College, Needham transferred to the University of Maine his sophomore year. His enthusiasm — drawn from a fascination in how invisible-to-the-eye pathogens can shape society — has remained steady and engaged through his education.

Leading into his senior year, Needham traveled to Senegal with UMaine’s Partners for World Health (PWH) chapter. A grant from Projects for Peace and UMaine’s Cohen Institute for Leadership & Public Service funded the trip for Needham and three other students. Over a week’s span, they helped 445 people from different parts of Senegal receive primary care from medical providers. They also helped interview and educate 200 pregnant women as an initiative by PWH to lower the infant and maternal mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa, an experience that brought a sense of reality to Needham’s research on group B streptococcus (GBS) — a leading cause of newborn infectious disease with high rates in Africa.

A year of successive failures to create mutant strains of GBS taught Needham that research is more failure than success. Each failure was his motivation to try again with the determination that every next time would reveal the solution. He traces his skill and confidence in the laboratory back to “Phage Genome Discovery,” microbiology students’ first intensive research course. He returned as a teaching assistant during his junior and senior years and helped grow the skill and confidence of first-year students, like the course had done for him.

Needham’s honors thesis titled “Prophage-Driven Regulation of Nutrient Transport in Group B Streptococcus” was supported by the Maine INBRE Research Fellowship and Carolyn E. Reed Premedical Thesis Fellowship and presented at two UMaine Student Symposiums and two Maine Biological and Medical Sciences Symposiums.

In addition to his role as vice president and recycling coordinator for PWH, Needham is the president of the UMaine Health Professions Club, which he re-established during the COVID-19 pandemic to connect premedical students with each other and resources. He worked as a gross pathology intern at Dahl Chase Diagnostic Services between his sophomore and junior years. Since he was a rising sophomore, he has worked as an inpatient pharmacy tech at Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center, where he also volunteers his time through PWH.

Needham plans to specialize in infectious disease or pathology. He will take a gap year between graduation and medical school, and hopes to continue volunteering with organizations such as PWH.

You’ve been described as someone who is engaged in the classroom environment, thoughtful and respectful toward helping other students. Why are these important to you?

I love learning about the field that I am in, which keeps me engaged. Microbiology is fascinating to me and has been for a long time. It’s cool that something we can’t even see can cause such massive effects — on an individual, how pathogens interact with their hosts to cause a diverse range of conditions, and on the population, how pathogens such as COVID-19 or the bubonic plague have shaped humanity. I feel like I learn about a new microbe every week and the weird things that it can do.

I also very much enjoy being a teaching assistant (TA) for the “Phage Genome Discovery” course. It was such an important and fundamental experience for me, and being able to potentially give that experience to another student is an amazing feeling. The phage course and the Molecular and Biomedical Sciences department — really UMaine as a whole — is great and unique in how students support each other. When you see students succeed in the class, get involved in other research and activities and become interested in the content, you know that you had a hand in making that happen.

Faculty in our department care about us and go above and beyond for their students. Knowing they care about my success motivates me even more. Dr. Edward Bernard, a professor I worked with as a TA in the phage course, walked around during one of the midterm exams to ask all the students their favorite pizza toppings. He was going to order pizza to congratulate and celebrate them for doing so well in the class. There are other amazing student-run organizations such as the Microbiology Club that build community between students. I also helped bring back the Health Professions Club to provide students, including myself, with resources and connections for their difficult pre health journey.

What encouraged you to independently troubleshoot and pinpoint problems in your own research? — as opposed to asking for help.

A huge part of doing anything is knowing when to ask for help. Research is like 95% failure, which is why it can be so fun and motivating. You’re always working to fix protocols, improve assays, figure out why something that has worked for three years doesn’t anymore. Learning to deal with failure was super important for me. Research was one of the first times I faced something that I kept failing at. I tried for well over a year to create a single mutant strain of group B streptococcus (GBS). While I eventually did, it took an entire year of failure after failure after failure. It motivated me even more, and I worked hard to troubleshoot and to figure out what was going on, and I also turned toward my resources — the principal investigator in my lab, my graduate student mentor, my other lab mates and friends. A lot of the skills I practiced arose from the phage course, an introductory research-intensive class for first-year students. The experience of failure in research was super important as I learned how to accept it, deal with it and come back from it.

What is your motivation to volunteer?

In the words of Elizabeth McLellan, the founder and CEO of Partners for World Health (PWH), the first time we met: “Find something greater than your own self interest. When you commit to it, it will grow.” Those words have stuck with me the past few years. I’ve gotten to see and help UMaine’s chapter of PWH grow over the past few years, and it has helped me grow as a person. I’ve gained friends, connections and amazing experiences from volunteering. I get to explore hospitals, handle medical devices and equipment and meet medical providers and hospital/clinic staff.

If volunteering isn’t an enjoyable experience and if it doesn’t motivate you, you just haven’t found the right thing to commit to yet. I love what I do, and that’s why I keep doing it. It’s also a way of giving back to the community that is helping raise you. A community is a two way street. I’ve gotten so much support from UMaine, my hometown, my family and my friends; volunteering is one way of paying that back.

What was most eye-opening about your trip to Senegal?

PWH runs a program called Project 10,000, the goal of which is to lower infant and maternal mortality rates in sub-saharan Africa by providing sterile birthing supplies and education to 10,000 pregnant women. I helped interview and educate about 200 pregnant women to gather information for the providers, processed forms and assisted with vitals and assessments. Our group of student volunteers learned a lot from the providers, such as how to interact with patients with a language and cultural barrier through a translator, how to care for them, how to treat them with empathy and how to work with limited resources. People tend to think of these missions as dramatic, where doctors miraculously deliver babies or go and administer life saving medical treatment. Those things definitely happen, but from what I saw, it’s the simple human connections we build with people that make a world of difference.

As I was wrapping up one of my first Project 10,000 interviews, I asked the pregnant woman, “Do you have any questions?” She immediately started crying, and I was terrified that I had said something wrong. I turned to the translator and asked what happened. Through tears, the woman told the translator and the translator said to me: “She is crying from happiness because she has never been asked that question before.”

Our group got to see the work we do in Orono in action in Senegal. Our chapter sorts medical supplies and ships them to Portland. Providing pregnant women with such supplies in Senegal, some of which could have passed through our hands in Orono, revealed the full picture and the impact of what we do back home. It turned statistics into real faces and created a sense of connection. When you put a face to the numbers for maternal and infant mortality rates and learn their names, their children’s names and their occupations, it becomes much more real. It also connected to my work with GBS, a leading cause of newborn infectious disease. Africa especially has some of the highest rates. GBS lives asymptomatically in about 1:5 women and can infect the infant in utero or during labor, potentially causing severe disease.

What impact did the Senegal trip have on your career ambitions?

One of the main things I will take away from the trip is the amazing impact that a physician can have on a community. There were so many rural Senegalese patients with conditions that were untreated or poorly managed, because they had no idea what was wrong with themselves. Even if they were somehow able to see a doctor, they were not given the time and care to help understand their conditions. Many people came in with severe hypertension, because they didn’t have access to blood pressure monitoring devices or thought hypertension medications were temporary like antibiotics.

People joke that medical students and physicians get weird questions from their friends and

family, but it’s because of trust and the desire to understand their health. A primary care patient that I saw in Senegal while shadowing a physician had a condition that was most likely caused by his hypertension medication. The patient was grateful that the physician was able to explain the condition to him and why it was happening. He returned with a hand sewn dress that he had made to express his gratitude to the physician. Physicians are here to support, educate, help people and get them back to a healthy state, so they can enjoy life and, in this case, follow their passion of sewing beautiful clothing.

Contact: Ashley Yates; ashley.depew@maine.edu