UMaine supports teaching of Wabanaki Studies in K–12 schools

Last fall, Grace Bermeo was in her last semester as an elementary education major at the University of Maine, doing her student teaching at Portland’s East End Community School.

The school was piloting Portland Public Schools’ Wabanaki Studies curriculum, which weaves lessons about the history, culture, language and more of Maine’s original inhabitants — the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet/Wolastoq people — through various subjects.

“I went to all the teacher meetings in August, where we discussed the curriculum in-depth, and because we were the first group to go, we were kind of the guinea pigs,” says Bermeo, who taught the curriculum in a third-grade class with her mentor teacher.

Having moved from New York City to Maine at age 10 and having graduated from Biddeford High School before going to UMaine, Bermeo says she learned a little about the Wabanaki people growing up. But her knowledge didn’t feel sufficient for teaching the curriculum.

“Before I would teach the lessons, I was teaching myself, too,” she says.

One lesson involved a field trip to a dam on the Presumpscot River in Westbrook, where students were challenged to think about how the river was used by the Wabanaki versus European settlers.

“We talked about how the Wabanaki relied on the river for food, for travel, and how the Europeans came in and built dams and took the river away. It was really interesting for the students and for me to learn about that and think about how it still has an impact,” Bermeo says.

The UMaine College of Education and Human Development has launched a pair of initiatives to help education graduates like Bermeo be better prepared to teach Wabanaki studies when they get jobs in Maine schools. Starting this school year, all pre-service teachers in the college are required to complete the University of Maine System’s Dawnland micro-credential, a self-directed online course exploring the history of the original people of Maine. Starting next year, the college will require teacher education students to take a semester-long class called Teaching Wabanaki Studies, which is being offered for the first time this spring through the Native American Studies program at UMaine.

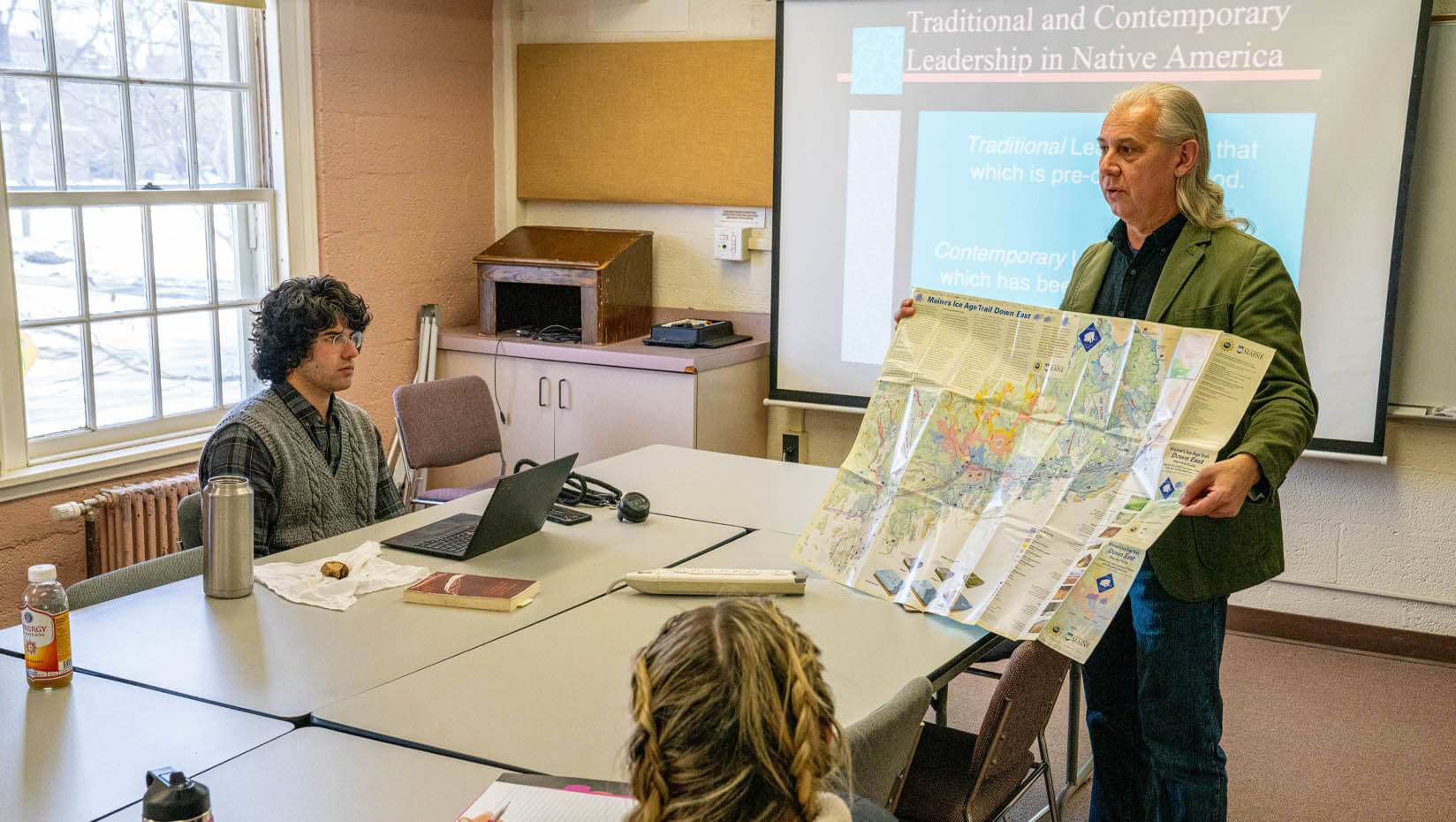

The micro-credential and the class were both developed by John Bear Mitchell, a citizen of the Penobscot Nation from Indian Island and a lecturer in Wabanaki Studies, among other roles at UMaine.

“We have an opportunity at UMaine to be a model for how this is done in other places,” says Mitchell. “We’re taking an Indigenous knowledge approach. In other words, we’re going to be doing and creating.”

The course is designed to provide students with eight to 10 example lesson plans and supplementary materials that they can take with them after graduation. It also covers how to create additional lessons and connect them to the Maine Learning Results. Importantly, the lessons span the list of subjects taught in elementary and secondary schools, including math, science and engineering, health, language arts and social studies.

“Indigenous knowledge is broad, and the curriculum has to reflect that,” Mitchell says. “We exist in every single subject.”

A 2001 state law requires K–12 schools in Maine to teach Wabanaki history and culture. The law is still widely referred to by its bill number, LD 291, which was sponsored by the Penobscot Nation’s then-tribal representative to the Maine Legislature and UMaine alumna, the Hon. Donna Loring.

Some have criticized the state and school districts for failing to fully implement the law. Last October, a group led by the Wabanaki Alliance, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Abbe Museum and the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission released a report that says the Maine Department of Education has not “meaningfully enforced” the law and that schools don’t “consistently and appropriately” teach Wabanaki Studies. The report also called teacher training and professional development on the topic insufficient.

The two initiatives in the College of Education and Human Development were in the works before the report came out. Last year, the college created a committee to look at ways it currently supports implementation of the Wabanaki Studies law and to explore how to incorporate more perspectives and knowledge about the Wabanaki people into courses for aspiring teachers at UMaine. In addition, Mitchell led a Wabanaki Studies strand at last summer’s inaugural UMaine Educators Institute, which more than 120 Maine teachers participated in.

“We are the largest teacher education program in the state, so it’s our responsibility to ensure the educators who serve our communities are not only able to meet the letter of the law, but to go beyond it and provide specific and relevant lessons about the first people of Maine,” says Penny Bishop, dean of the College of Education and Human Development.

Mitchell, who has been involved with adding Wabanaki Studies standards to the Maine Learning Results since LD 291 passed and who has worked with Maine DOE and other organizations on teacher training for several years, agrees that the goal should be to go above and beyond the minimum requirements of the law. He notes that many schools and school districts have taken it upon themselves to create programs and curriculum to do just that.

“Things rarely happen quickly in education, but we’ve made great strides in 21 years,” Mitchell says. “From a standalone law to now, all of the tribes have developed their own curriculum, all are working with local school districts. So, we have schools interested, we have the College of Education and Human Development interested.”

After introducing the Wabanaki Studies curriculum at East End Community School in the fall, all elementary schools in the Portland district are now teaching it. The district also has plans to introduce it at the middle and high school levels during the 2024–25 school year. Similarly, the Bangor School Department is piloting a Wabanaki language and history course at Bangor High School this spring.

About halfway through her student teaching, Bermeo, the recent UMaine graduate, was hired as a full-time teacher at Portland’s Rowe Elementary School, where she is currently teaching the Wabanaki Studies curriculum to a class of second graders.

Bermeo completed the Dawnland micro-credential course in December and says it helped her gain a better understanding of the history of the Wabanaki people that will have long-term benefits to her as a teacher.

“I feel a lot more confident than I did in August or September,” she says, adding that she wishes she were still in school so she could take the Teaching Wabanaki Studies class.

“My students in the fall and the class I have now, they love the curriculum,” Bermeo adds. “They are so engaged and so excited to connect what they learn about the Wabanaki people to their own lives and to the other topics we’re learning about.”

Contact: Casey Kelly, casey.kelly@maine.edu