John Linehan: Wild Kingdoms

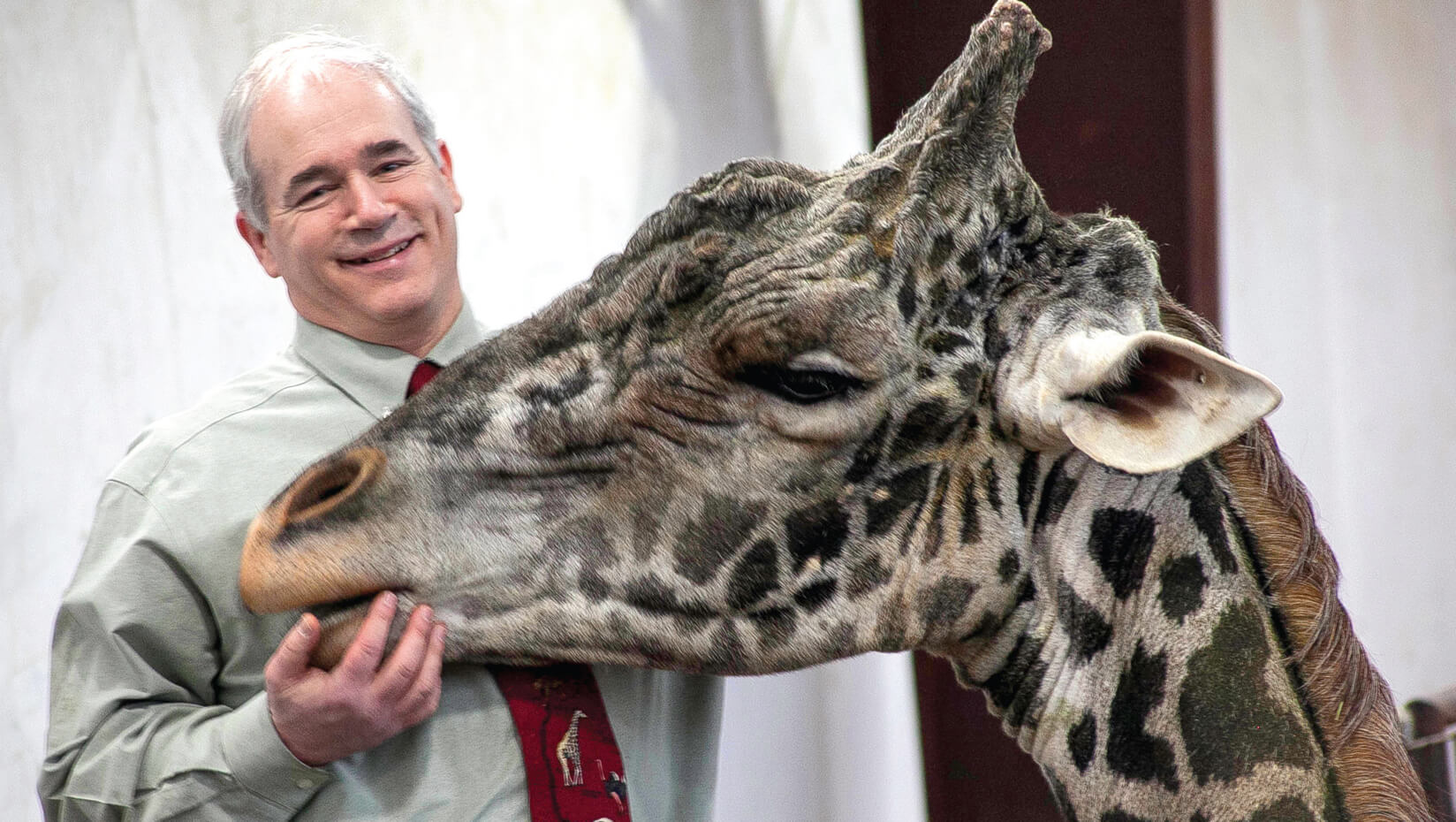

John Linehan and Beau, Franklin Park Zoo

Photo courtesy Zoo New England

In 1980, John Linehan planned to use his University of Maine degree in wildlife management to improve the lives of wild animals by working in Africa, Alaska or Maine.

While waiting for that dream job to materialize, he took a temporary position in what, for him at that time, was an unlikely field — zookeeping.

As a child growing up in Canton, Massachusetts, Linehan was fascinated by the animals, but found zoos sad and depressing in their approach to helping the public appreciate the beauty and importance of animals.

Years later, the same was true when he got his first zoo keeping job at Boston’s 72-acre Franklin Park Zoo, founded in 1912. And it wasn’t just at that zoo. The nearby 26-acre Stone Zoo in Stoneham, Massachusetts, founded in 1905, held the same disappointment.

“When I first started, the two zoos were a joke. They only had farm animals and birds for exhibits. Not only that, inebriated people could just walk right in with no problem, and people could even bring their dogs in. It was an unsafe situation for both animals and humans,” says Linehan.

Yet Linehan stayed on because there were so many opportunities for him to make a difference. Every time his weekend came and he was off work for a couple of days, he would always think, “Will these animals be OK if I’m not there?”

He worked as a temporary laborer, zookeeper, head zookeeper, and mammal curator for 21 years. Throughout, Linehan voiced his opinions, concerns and enacted changes in an effort to improve Franklin Park for the animals and the patrons. He also worked to help establish Zoo New England — a nonprofit corporation created in 1991 to operate both Franklin and Stone zoos.

In 2002, Linehan was named president and CEO of Zoo New England, with a depth of experience and high expectations to move the zoological parks more in the direction of educational outreach and conservation.

Today, Zoo New England’s mission is to “inspire people to protect and sustain the natural world for future generations by creating fun and engaging experiences that integrate wildlife and conservation programs, research and education.”

“Ultimately, modern zoos are a critical component in introducing urban kids to nature,” Linehan says. “The zoos introduce the kids to the environment that will lead to a heightened appreciation and understanding of the animals, which will hopefully lead to learning about them in a higher education and, ultimately, will lead to them conserving the animals they grew to love.”

Zoo New England is committed to creating an emotional and intellectual connection to animals. Rather than making zoos a passive experience in which people simply view the wildlife, Linehan is working to make the exhibits more interactive, particularly so that children can learn while having fun.

To jump-start that process, Franklin Park is building a new children’s zoo that will have fewer animals, but is more interactive and features learning-based activities.

“The planet is like a fuse. If we don’t do anything, soon enough all biological ecosystems will start unraveling,” says Linehan of the importance of educating younger generations.

Linehan’s work focuses on conserving ecosystems and everything in them. That’s why Zoo New England is a participates in conservation projects, locally and around the globe.

For example, one of Franklin Park Zoo’s head veterinarians also does fieldwork in the cloud forest area of Panama, helping to reintroduce the golden frog that is extinct in the wild. His work involves not only the amphibians, but also human inhabitants in the area, recruiting them to help in the reintroduction effort.

In addition, Franklin Park has introduced a conservation awareness-raising Quarter Token program, called Quarters for Conservation,in which 25 cents of patrons’ admission fees goes toward conservation projects. Visitors receive a token upon admission that they then can deposit on-site toward one of a handful of conservation projects. Not only do the visitors know that they are helping to conserve species, they can be involved in deciding which project to fund.

Linehan admits that, even now as a zoo CEO able to bring his leadership vision to bear on improving zoos, he still misses hands-on zookeeping. Now he can only watch as zookeepers and curators perform the duties he used to do. Today he is more of a facilitator, making sure the zoos are running efficiently, and the animals are safe and healthy.

He also gets great satisfaction in helping people — from zoo patrons and donors to urban youths in his after-school programs — gain a healthy perspective on the wild kingdom and its place on the planet.

Making a difference is important to Linehan.

“I want people to come to my zoos and think, ‘Wow, those animals are incredible. What can I do in my life to make sure they don’t go extinct?’” he says.

People need to know that ecosystems are like a neighborhood, says Linehan, and that we have a reliance on other animals and that we share the planet with them.