More finds 6-year climate irregularity impacted World War I, ‘Spanish flu’ casualties

A once-in-a-century climate deviation that resulted in torrential rain and cold air over Europe from 1914 to 1919 likely increased the number of people who died during World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic.

The documented severe, incessant rains and unusually cold temperatures impacted major battles from 1914 to 1918 on the Western Front. “That included the battles of the Somme and Passchendaele, during which more than 1 million soldiers were killed or wounded,” says Alexander More, lead author of the study titled “The Impact of a Six‐Year Climate Anomaly on the ‘Spanish Flu’ Pandemic and WWI.”

GeoHealth, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, published the study.

The weather also exacerbated the H1N1 pandemic known as the “Spanish flu,” says More, a climate scientist and historian at Harvard University and the University of Maine Climate Change Institute, and an associate professor of environmental health at Long Island University.

The pandemic, which included an initial and a second wave, claimed an estimated 50 million lives between 1918 and 1919. It also infected 500 million people, which was one-third of the world’s population at that time.

“Besides sending a warning for our own pandemic’s second wave, this article proves once again, the insights we gain with interdisciplinary research, connecting data from fields that were once separate — climate science, history and public health — are now being brought closer together by projects like ours, spurred by the urgency to find solutions to the two major crises we’re facing: man-made climate change and the pandemic,” says More.

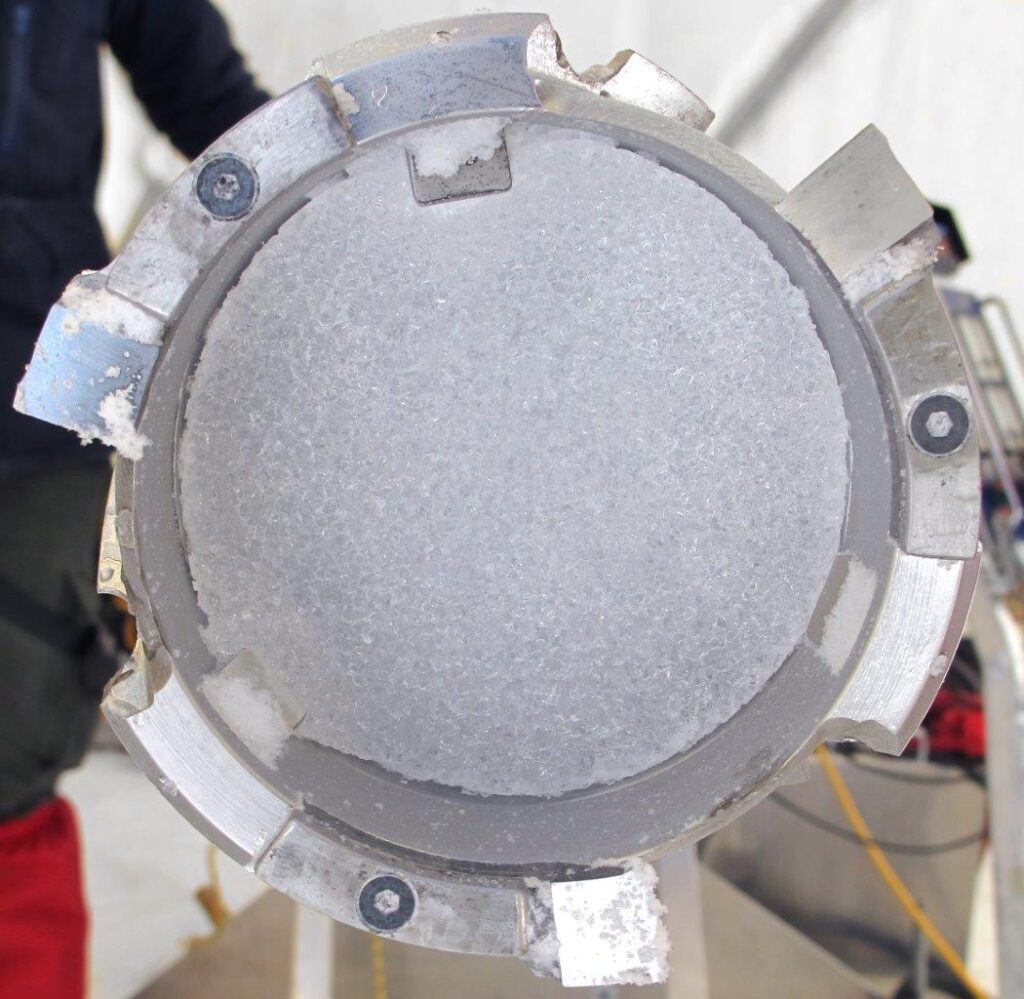

For the study, More and colleagues reconstructed environmental conditions over Europe during the war using data from an ice core from the Colle Gnifetti Glacier in the European Alps. CCI scientists used next-generation laser technology to provide the ice core data.

More and Christopher Loveluck from the University of Nottingham compared environmental conditions to historical records of deaths during the World War I years. The ice core record backs up historical accounts of flooded trenches and soldiers dying from drowning, pneumonia and infections.

Paul Mayewski, CCI director and co-author, says this research underscores the value of interdisciplinary discovery, “which is only heightened under the modern pressure of climate change, pandemics, disruptions to economies, and other threats to humans and the ecosystem.”

More also discovered that the extremely high precipitation in fall 1918 paralleled the pandemic’s mortality pattern. The increased precipitation was part of the six-year climate anomaly that brought rain and cold air from the North Atlantic over Europe, in a sustained Icelandic low pressure system.

More and Mayewski say a likely reason for the anomalously cool, wet period was the war. They say the major increase in dust and explosives could have cooled the local atmosphere and formed nuclei for precipitation.

Famines and the disruption of migratory patterns of wildlife — including the mallard duck, one of the main reservoirs and vectors of the H1N1 influenza — also likely contributed to weakening the population and increasing mortality.

Because the birds were close to military and civilian populations, a particularly virulent strain of H1N1 influenza may have transferred to people through bodies of water.

Philip Landrigan, director of the Global Public Health Program at Boston College, says it’s interesting to think that very heavy rainfall may have accelerated the spread of the virus.

“One of the things we’ve learned in the COVID pandemic is that viruses seem to stay viable for longer in humid air than in dry air,” says Landrigan, who was not connected to the study.

“So it makes sense that if the air in Europe was full of humidity during those years of World War I, that the transmission of the virus might have been accelerated.”

More says as we stare down a second wave of COVID-19 this fall, we should be mindful of the impact that climate and environmental conditions have on disease.

“Several ongoing epidemics are affected by man-made climate change, as animals and the diseases they carry migrate away from normal habitats to find food and water now made scarce by our impact on the environment,” he says.

In addition to More, Mayewski and Loveluck, study co-authors are Heather Clifford, Michael Handley, Elena Korotkikh and Andrei Kurbatov at UMaine; and Michael McCormick at the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard University.

The research is the result of a collaboration of the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard and the CCI, with ongoing contributions from researchers at LIU in New York City, and the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. The Historical Ice Core Project is funded by Arcadia, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.

Contact: Alexander More, afmore@fas.harvard.edu, 617.417.5608; Beth Staples, beth.staples@maine.edu; Media kit available here