Sports Writers

Tennis star Serena Williams does it. Olympic legend Michael Phelps did it during the 2012 London Games. Baseball player Carlos Delgado was profiled in a 2006 New York Times story for doing it.

So did the soccer teams Richard Kent coached around 30 years ago when he was teaching high school students in the western Maine town of Rumford.

Now an associate professor in the University of Maine’s College of Education and Human Development and the director of the UMaine-based Maine Writing Project, Kent has developed the concept of team notebooks in which athletes spend time in the course of a sports season writing evaluations of their preseason goals, feelings about games they have played and watched, and postseason outcomes.

He relates the notebooks concept to differentiated learning, which acknowledges that the variety of ways in which students learn in a classroom (or on a field, court or wherever athletes do their work) requires a teacher (or coach, trainer or adviser) to present a variety of learning techniques.

For athletes — from Olympians to high school players — Kent’s research shows that keeping a journal is a way to decompress, unpack mentally and think critically about the outcome of a game, match or other sporting event. Some use journaling in preseason to clarify their goals for the upcoming competition, or in the postseason to set themselves up for off-season training. Others write while an event is in progress. Delgado, for example, was known to keep notes in the dugout when he wasn’t playing.

“The team notebook is a way for athletes to communicate more directly with a coach, but even more than that, for them to think about learning in different ways,” Kent says. “What we know about learning these days is that we all learn differently, and in fact it’s differentiated instruction for coaches. This really mirrors what we know in the College of Education and Human Development of the effective classroom, which is that we address learners where they come from.

“In other words, we all have different ways to learn. Some of us do well by writing about it, some of us need to talk about it, some need to think about it, and some need a little bit of everything. That’s the bottom line with this research, that an effective coaching practice has lots of different ways for athletes to consider their performances and their training, and writing is one of them.”

Although athletes have been journaling on their own for years, Kent’s notebooks are among the first of their kind to standardize the process with specific writing prompts and consistent questions. Several institutions have starting using Kent’s model notebooks and tailoring them to their own needs, which Kent encourages. Coaches at Southern Virginia University, Gonzaga University, University of Missouri and Temple University have adapted the notebooks and implemented them in their programs.

Kent’s ideas about athletes and journaling started about 30 years ago during a flight from Europe. At the time, he was Maine’s state soccer coach, returning with a group of players who had competed in a tournament. It wasn’t a successful trip for the team. It hadn’t fared well against its European opposition.

That’s when Kent had the idea to have the players write about their experiences and how they felt about the trip. Problem was, the only paper available on the plane was the airline’s airsickness bags.

“Some kids wrote six sentences, but some wrote on both sides, ripped open the bags and wrote inside,” says Kent, the author of 10 books, including Writing on the Bus: Using Athletic Team Notebooks and Journals to Advance Learning and Performance in Sports, The Athlete’s Workbook and The Soccer Team Notebook. “I sat there and read them and thought, ‘Holy mackerel, this is really interesting.’ I started incorporating more writing activities with my teams.”

While Kent had used writing exercises with his soccer teams for years, his research for the notebooks began in 2005-06 when a University of Southern Maine soccer coach gave them to his team as a pilot project for a season. Also around that time, Kent met with David Chamberlain, an elite World Cup cross-country skier who grew up near Kent in Wilton, Maine. Chamberlain had long kept journals and training logbooks, and allowed Kent to study five years’ worth of his writing.

Kent looked at Chamberlain’s logs through a writing-to-learn lens advocated by William Zinsser, a well-known writer and teacher, and others who believe writing enables us to find out what we do — or don’t — know about a subject.

“The concept of writing to learn allowed me to see what types of themes would emerge,” Kent says. “Then I would interview Dave about those themes, one of which was he was thinking about whether he wanted to stay with ski racing or move on to become a coach. He wrote seven pages grappling with this issue.

“I do a great deal of narrative analysis, where you look at a piece of writing and think about: What direction is this athlete going with this? How do the themes merge with his thinking and what he ends up doing? It ended up that he stayed with skiing for another three years.”

Kent also asked UMaine head soccer coach Scott Atherley and members of his staff for feedback on the notebooks. A friend who was then an assistant coach with a professional basketball team also reviewed them.

“Everybody was very accommodating and offered me ways to reconstruct the notebooks,” Kent says. “Like with anything in writing, there is always a process of revision. When I work with teams or coaches I say, ‘Listen, make it your own.’ There isn’t one right way to do this. You have to revise and be comfortable with it. I used team notebooks five days a week, but you might want to do it once a week.”

Kent believes journaling makes athletes more accountable in a number of ways, and his work with Chamberlain provided a good example of this. At the higher levels of endurance skiing, athletes in training measure the levels of lactic acid in their blood as an indication of fitness level. Skiers who journal, along with tracking their lactic levels, can establish patterns that reveal how factors such as sleep, nutrition and mood affect a training session. The journals are frequently shared with coaches, sometimes via email.

“They write about it, talk to trusted advisers about it, and then make decisions about how they’re going to adapt their training,” he says. “Writing is a critical component for all of this and I think it’s been a missing link in athletics.”

Journaling can be a way for athletes to learn to take emotion out of analysis and think about categorizing, moving on from a win or loss.

“The mere act of writing slows us down and makes us think,” Kent says. “You start with the self, think about what you need and then move forward. It’s the same with the team notebooks. After a match, you sit and think: ‘What did I do well in this match, what did I struggle with? How did the other team do against us? What advice would you give as a coach to the other team about the way they played? It helps them as writers to learn theory and how to think more deeply about the way they look at sports, but also sort of turns them into coaches, which I think is a great thing. It helps them consider the sport through a different lens.”

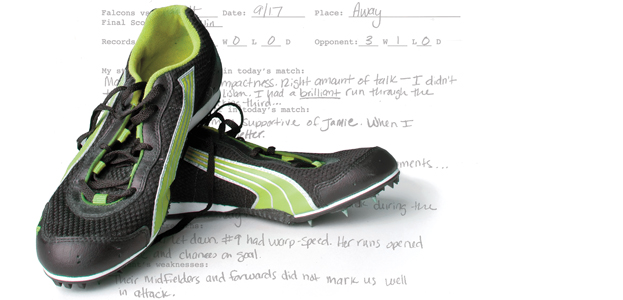

The basic athlete notebook contains five sections, complete with writing prompts based on the templates Kent used while he was coaching soccer. The notebook begins with a page called Preseason Thoughts, which the athlete is meant to fill out before regular-season competition begins. The athlete is asked to write about his or her individual and overall team strengths and weaknesses in the previous year, preparation done in the off-season for the upcoming season, goals for upcoming season, and information about his or her class load for the upcoming season.

The next section, Competition Analysis I, asks athletes to reflect on the outcome of a game or match in which they have participated. The writing prompts include individual, team and opponent strengths and weaknesses, suggestions for adjustments in subsequent games or matches, and what made the difference in a win or loss.

That section is followed by a Competition Analysis II, which is meant to be completed by players following a match they have watched but not participated in. It directs them to write their observations of the two teams, including strengths and weaknesses, halftime adjustments, comments about players at different positions, key moments of the game, and a final analysis that asks the players to think like a coach.

A page called Postseason Thoughts allows the player to think about strengths and weaknesses as an individual and a team, describe plans to improve in the off-season, reflect on preseason goals and discuss how he or she is handling schoolwork. The fifth section, Athlete’s Notes, is a kind of free space for players to store handouts, sketch plays and keep notes.

One of the trepidations teams often have when confronted with the notebooks is the amount of time that should be dedicated to journaling. This is particularly true for student-athletes who might have homework to do following a game, or coaches who are already overburdened. But Kent has designed the journals so they take a few minutes to complete. Athletes can write as little or much as they choose, and coaches can take as much time as they want to read the notebooks.

Coaches nationwide have contacted Kent to praise the notebooks for having helped their teams become more pragmatic and thoughtful about the way they analyze a game and a season. Kent sensed the power of the notebooks himself one night years ago following a soccer game that his team won after a late comeback.

The members of his winning team had formed a circle on the field, pulled out their notebooks and were busy writing. On the other side of the field, the members of the losing team milled about aimlessly, walking off into the darkness.

“I thought about the (losing team members’) drive back to their school and wondered how the players would unpack the match with one another,” Kent says. “I looked at my kids and how purposeful they were about their writing and their thinking, and knew that this was something that was special and helped create a common language for the team. That’s what I have explored and expanded through this research.”