You Are What U Eat

Getting UMaine to commit to 20 percent “real food” by 2020 is a challenge for undergraduates

By David Sims

UMaine Honors College senior Audrey Cross has been working hard these past two and a half years trying to get students a seat at the table—the dinner table, it could be said.

As a member of the Honors College Sustainable Food Systems Research Collaborative, or SFSRC, Cross has worked on a national food sustainability and justice movement driven by college students called “The Real Food Challenge.”

The students are organizing for systemic changes in both how colleges procure food and how student and stakeholder voices are engaged in dialogue and decisions. The goal of the campaigns is to get college presidents across the United States to sign the Real Food Campus Commitment, which commits a college campus to work for at least 20 percent “real food” by the year 2020.

The student-led work, which includes exacting, selective audits of every item that enters the UMaine food system in an effort to gauge if it is from local/community-based, fair, ecologically sound and humane food sources—“real food”—is challenging indeed.

“It takes a lot of time and effort for students to track every single food item to its source to figure out if it counts as real food but, in the end, it’s a really great exercise in that it gives students an expertise, which alters power dynamics,” Cross says. She adds, “That is, students do all this research and their work determines the percentage of real food, which gives them power over the analysis of the data because usually students are sort of like customers rather than engaged in the process.”

And what does that power provide? “A seat at the table that hopefully can lead to product shifts,” Cross asserts.

That potential product shift begins with a process/tool called the “Real Food Calculator.” In the process, students are provided with invoices from campus dining services or a food service contractor from two sample months of campus food purchases. The Real Food Challenge students then research each item and work with the distributors to figure out what certain codes mean to determine if the items have the certifications that make them count as humane, fair trade or ecologically sound, or if the items are sourced from a community-based business within a 250 road-mile distance of the university or college.

Says Cross, “We then have to research if there have been any recent labor violations associated with the food businesses, for example, through searching the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s database. We also have to determine all sorts of things about the ingredients. It’s a very rigorous process.”

It’s a process that has already led to positive change at UMaine.

When Cross helped Ashley Thibeault ’15 run the Real Food Calculator with data from the 2012-2013 academic year, they discovered there was a Japanese mining and agricultural company that UMaine purchased cashews and baby corn from that had been cited for slavery violations through 2002 in its mining operations. Since under the Real Food definition slavery disqualifies a company for ten years, those products could not count as “real food.”

“When UMaine’s dining director, Glenn Taylor, found out about it, he said it was a simple product shift and he found another source,” Cross notes. She adds that Taylor has been very supportive and participatory in the Real Food Challenge and has made some food substitutions simply because, according to Cross, he knows it’s important.

“He’ll say, ‘Guess what I just figured out—we’re now getting chicken and eggs from Portland in the Memorial Union,’ which is huge because the Union is sort of a test bed before foods go to the dining hall—it’s smaller demand, so you can start with smaller orders, and if the product is successful it can then be used in dining halls.”

A new paradigm

Cross was among the first group of SFSRC fellows, which also included Danielle Walczak and Ashley Thibeault. A new initiative of the Honors College that grew out of broad student interest in food systems research, the SFSRC brings together students, faculty, and community partners in an interdisciplinary approach to addressing problems of food production, food distribution, and hunger. (Cross notes that UMaine Honor College students Andrea Flannery and Shannon Brenner both did food-related research prior to the SFSRC, as did non-fellows Carolyn Stocker and Ethan Tremblay who graduated in 2015.)

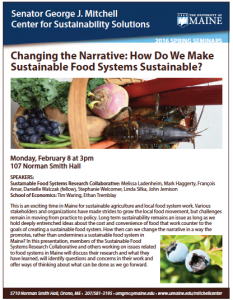

Initial support for the SFSRC was provided in 2014 by a seed grant from the National Science Foundation’s Sustainability Solutions Initiative (SSI), which evolved into the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions when the NSF grant concluded. The Mitchell Center’s stakeholder-engaged, solutions-driven, interdisciplinary research approach was a perfect match for the SFSRC project, which itself breaks new ground for the Honors College.

The SFSRC represents a new approach for the Honors College in that the honors thesis work is not conducted strictly between a student and his or her thesis advisor but, rather, is done in a more collaborative, interdisciplinary way that brings other fellows, faculty members, and community partners into the process.

The Honors College has traditionally paired a faculty advisor with an individual student for thesis projects but, says Cross, “Under the new paradigm of the SFSRC work they really mixed things up with how thesis research works so it’s now a more collaborative learning environment. We’re all working on our separate theses in the same room and sharing articles with each other— and discussing those— and helping each other out.”

Notes Mark Haggerty, Rezendes Preceptor for Civic Engagement, Honors College, “The SFSRC is a network that brings together and supports students, community partners and faculty in analyzing and generating solutions to long-term food systems problems.”

So what’s driving Honors undergraduates toward food systems research? Cross believes it’s because the topic is very central to her generation because they grew up in a time when a lot of media attention was focused on food issues—genetically modified organisms, sustainable agricultural practices, hunger, obesity, locally grown, etc.

“It’s something my generation is increasingly aware of because of all these things that have been revealed about the food system in documentaries and books and articles… things that are sort of shocking to a lot of people I know.” Cross says.

Growing up, Cross did love farmer’s markets and was “into” natural and local foods, but never engaged in food activism or thinking deeply about all parts of the food system. With an interest in botany, in her first two years at UMaine she took a lot of plant classes— such as taxonomy and biology—but when she began rooming with now former SFSRC Fellow Thibeault, food systems came into sharp focus.

“I lived with Ashley and ate most meals with her in the dining hall, and we talked about food issues because she’d worked with The Food Project in the Boston area.” The Food Project hires high school students to both work on a farm and learn about food systems issues—labor rights, sustainability, access—and does a community supported agriculture program and sells in farmer’s markets.

“Living and eating with her in college was very educational and transformative for me,” Cross recalls. “Just talking with her, I was learning facts about things like concentrated animal feeding operations, hormones, antibiotics, GMO papayas, injustices against farmworkers, and monoculture bananas. I was astounded.”

The Real Food Challenge work at UMaine actually started before the SFSRC got underway when three students went to a Real Food Summit. One of these students, Ruby Daybranch, started the campaign. “Ruby was here just a year but in that time she started a Real Food Challenge singlehandedly and when she left, she handed the project off to Ashley and me,” says Cross.

RFC students have been working for about three years to get the UMaine president to sign the Real Food Campus Commitment by doing Real Food Calculator audits and working with people from the Office of Sustainability, Dining Services and Auxiliary Services. “And they’ve been verbally supportive, and sometimes in actions as well, but they’re also bound by the bureaucracy, which can make things challenging,” Cross says. “So it’s been a long haul.”

To date, UMaine has committed to obtaining 20 percent local food by 2020 but has yet to sign on to the 2020 real food commitment. When Thibeault led the Real Food Calculator with data from academic year 2012-2013, she found UMaine got five percent real food at the time. There are currently five students running the Calculator for 2015-16, and Cross reports the percentage of real food has already surpassed five percent.

Democratic engagement and student activism

For her thesis, Cross is focusing on democratic engagement, student activism, and grassroots movements in the context of three years of Real Food Challenge work.

“I’m trying to draft the story of the campaign by looking back through my notes on administrative meetings and meetings within our student group, as well as a reflection document I maintained for a year, and press sources,” Cross says. “I want to assess the level and types of democratic engagement of students that was occurring and focusing on participatory democracy in that. So it’s looking at bringing about change, not just by voting with your dollar, but by being actively engaged and having a participatory role in making change happen.”

But it’s not just student voices that are valued in the process. The Food Systems Working Group, which is an integral part of the Real Food Campus Commitment the students want the UMaine president to sign, is comprised of a diversity of stakeholders. “We’re looking to have farmers and fisherfolk, policymakers and food service workers, farm laborers and alumni; we’re going to work to have these voices in the picture,” asserts Cross.

She adds that none of these peoples’ voices have been heard in the system with respect to how UMaine “does food”—how food is bought and from whom and where, and how people are served. So the working group gives at least some power to those stakeholder groups including, for example, a farmer who is not part the working group but knows someone who is and can communicate an issue important to him or her through that member.

Says Cross, “So that farmer’s voice can be included in how UMaine continues to operate its food system. It’s not like we asked farmers once through a survey and that’s the end of it. I think systemic engagement requires much more intentionality and focus on how we want to engage our community in a multi-directional flow of knowledge, opinion, and expertise. It’s not just comment cards; it needs to be people at the table.”

And the Mitchell Center helped set that table.

“The SFSRC has been engaged with the Mitchell Center where, last fall, we hosted an event that was about food service contracts, how food service works, and what ‘real food’ means,” Cross says. “And the ample conference room space at the Mitchell Center provided opportunities for more conversation and networking that was crucial.”

On May 2, UMaine Real Food Challenge students had a meeting with UMaine president Susan Hunter who, Cross reports, “said she was eager for a step-by-step plan on how to implement the Real Food Campus Commitment before signing.”