Sustainability Graduate Fellow Goes with the Flow for Safe Drinking Water

Story by Sonja Heyck-Merlin

“Where I grew up in Ghana, I became aware of the challenges many communities face in accessing clean and safe drinking water. That experience sparked my interest in environmental and then water quality research,” said Josephine Adu-Gyamfi.

These formative experiences coupled with her passion for problem-solving steered her educational journey. In Ghana, at KNUST-Kumasi, she received an undergraduate degree in geological engineering followed by a master’s in water resources engineering and management.

Hungry for more advanced training, Adu-Gyamfi, with her self-proclaimed can-do attitude, decided to pursue a second master’s at UMaine in civil and environmental engineering with a focus on water and the environment.

After her acceptance into the graduate program, Adu-Gyamfi applied and was accepted as a Mitchell Center Sustainability Graduate Fellow for the 2023-24 academic year. The program was a one-year experimental cohort of 11 graduate students across seven departments focused on networking, career-building, and peer-to-peer learning.

The cohort met regularly, working through professional development workshops designed by Mitchell Center faculty.

“I got the chance to meet other folks from different backgrounds who were in different sustainability sectors. The whole motive was to put our minds together to spark great synergy,” she said.

Maine’s per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contamination issues were a frequent discussion topic during her Mitchell Center meetings and in her classes.

PFAS are a group of chemicals widely used in industrial and consumer products such as nonstick pans, takeout food containers, and firefighting foam. They’re often called “forever chemicals” because they tend to break down very slowly or not at all.

PFAS can build up in the environment, impacting soil, and water. PFAS testing in Maine has revealed contamination in agricultural soils, private wells and public water systems, as well as crops, wildlife, and fish.

UMaine has been at the forefront of research efforts to identify and address the contamination.

While there were other water-related projects she could have pursued, like stormwater management, Adu-Gyamfi was drawn to UMaine’s PFAS research on water resources because it sits at the intersections of public health, environmental science, and risk management.

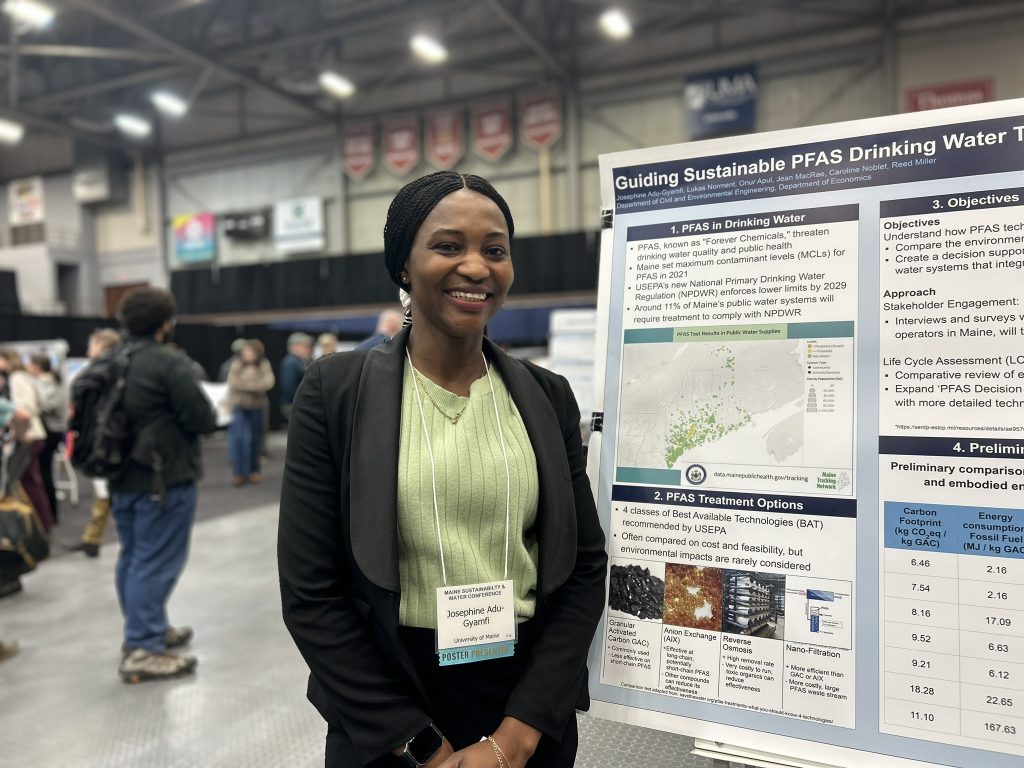

In the spring of 2024, Adu-Gyamfi joined a team working on Guiding Sustainable Enhanced PFAS Drinking Water Treatment Options, funded by the Maine Water Resources Research Institute, a program of the Mitchell Center.

Reed Miller, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, is her advisor and the leader of the project.

Adu-Gyamfi’s research looks at the best ways to remove these PFAS from drinking water while also thinking about the cost involved, the energy used, and the environmental impact of each method. This is especially relevant to public water systems in Maine that may need to invest in treatment to meet state and federal PFAS limits.

Currently, she is investigating the four “Best Available Technologies” as identified by the U.S. EPA as part of the final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR).

“I was particularly drawn to the PFAS work because of its urgent public health implications and the opportunity to evaluate treatment technologies from a sustainability perspective. The idea of helping communities make informed, cost-effective, and environmentally responsible decisions really resonated with me,” she said.

Adu-Gyamfi recently received a travel award to attend the The Universities Council on Water Resources (UCOWR) and The National Institute for Water Resources (NIWR) annual conference from June 3-5, 2025 in Minneapolis, Minn.

At the conference, she will participate in the graduate student poster contest and hopes to make connections that she said are so important for early career engineers like herself.

She’s also looking forward to the conference because anytime she can gain additional perspectives on water and sustainability issues, she’s all ears.

“You might not know the impact that the technologies and solutions you are working with will have on all the other systems — human life, agriculture, and animal life. The moment you put the minds of so many scientists, engineers, and people from different backgrounds, it helps to create balance to know if you’re on the right track in solving your issues or not,” Adu-Gyamfi said.