Mapping Meals: A Geographic System Searching for Food Waste

By Sarah Delmonte

By Sarah Delmonte

On November 20, 2023, University of Maine graduate student Courtney Baker delivered the first of several presentations at the Mitchell Center Lightning Talks event with a discussion on the development of a new food waste management tool.

“Approximately 40% of food produced in Maine is never eaten,” she began. “Maine wasted approximately 200,000 tons of food in 2019.”

According to Baker, food is the largest part of the solid waste stream in Maine. Most of the food that doesn’t get eaten ends up in landfills across the state, which presents a number of problems including wasting money and resources, harming the environment, and preventing good food from getting to those who might need it. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) found that $4 out of every $10 spent on food ends up wasted.

In response, Food Rescue MAINE, a Mitchell Center program, is working to launch the Maine Circular Food System Geological Information Systems (GIS) Map and Resource Locator.

What is a Circular Food System?

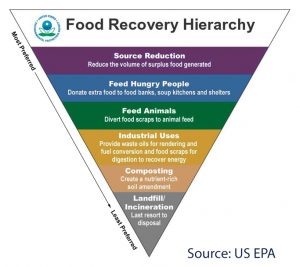

A circular food system is structured around the food waste reduction hierarchy, which consists of different levels that show where uneaten food should go. The top of the hierarchy highlights the most desirable goals such as reducing the amount of unwanted food through feeding people and animals. The lower goals in the hierarchy involve composting or turning food waste into fuel. At the very bottom is disposing of food waste into landfills.

A circular food system is structured around the food waste reduction hierarchy, which consists of different levels that show where uneaten food should go. The top of the hierarchy highlights the most desirable goals such as reducing the amount of unwanted food through feeding people and animals. The lower goals in the hierarchy involve composting or turning food waste into fuel. At the very bottom is disposing of food waste into landfills.

“Rather than food going directly to the garbage,” said Baker. “[It is] instead used to either feed people who would need that food or processed into another product, or [put] back into the soil so that agricultural producers can then produce more food.”

Essentially, the goal of a circular food system is to feed people, animals, and soil while simultaneously delivering profits to businesses and farmland with the lowest environmental impact. A circular food system increases the effectiveness of farms, reduces food insecurity and waste, and lowers the impact of food waste on climate change.

The Resource Locator

The tool that Baker is working to develop functions as an online map of food resource locations. Addresses of restaurants, food banks, grocery stores, bakeries, and other food providers can be categorized and filtered by users so they can find what best fits their needs.

“It’s been a really enlightening process because we’re trying to look at all the various stakeholders and food systems, integrate all that information into one place so that people can use this tool to make decisions,” said Baker in an interview. “In order to do that we met with countless stakeholders and they provided so much good information. Right now we are in the process of taking that information and outputting it into something that hopefully the highest number of stakeholders will find useful.”

While the tool is set to be accessible to everyone, Baker views the locator as a way to benefit businesses who need to figure out where to put their food waste.

“A big part of the reason why we’re developing this tool is that there are now various states in New England that have enacted policies limiting the amount of food waste that can be generated… They’re requiring companies to make sure their food waste doesn’t exceed a certain amount.”

With the resource locator, businesses are able to search for food banks in their area to donate food items that they cannot sell, allowing for a more sustainable method of eliminating their waste than sending food to landfills.

Getting Started

Getting Started

According to Baker, the locator tool began as part of a project launched through a GIS graduate course in 2022.

Susanne Lee, a Mitchell Center faculty fellow and program lead for Food Rescue Maine, worked alongside 30 students including Baker over the course of the semester to collect data sets and addresses to use with the locator tool. Students worked individually or in small groups to find location data or to turn addresses into data points for the map using a process called “geocoding”.

“There’s a quote that I will always remember from my very first introductory GIS course I took when I was an undergraduate,” said Baker. “They said, ‘about 90 percent of GIS is finding and gathering data’, which is absolutely true.”

Baker explained that her main role now in the development of the locator tool is meeting with stakeholders to seek out information that is missing from the data already collected. Stakeholders provided leads to other food resources, sites where resources could be located, and their own data to contribute to the tool.

“It’s been a process,” Baker stated. “It’s still a process because I’m still having to update this data consistently. We really want the data to be as accurate as possible when we launch the tool because, if it’s not accurate, that really mitigates the usefulness of this tool. We have been very particular about data.”

What’s Next?

Food Rescue Maine intends to continue updating the tool with the hope of launching the website next spring. According to Baker, the importance of the website lies in the fact that it compiles multiple different locations and information into one site, presenting a user-friendly way for both businesses and the general public to view where to find food sources.

Additionally, Food Rescue Maine hopes to expand their outreach to find more collaborators who are part of Maine’s food system and want to support a more circular approach. Stakeholders who may be interested can contact Food Rescue Maine at foodrescuemaine@maine.edu.

Resources

- Food Rescue MAINE website

- EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy

- A circular economy for food will help people and nature thrive

Sarah Delmonte is a Communications Intern with the Mitchell Center. Sarah is a senior undergraduate student majoring in English with a minor in Journalism.