Reflections on Remote Learning

Fall 2020 courses will be delivered via several modes of instruction. Among those modes are courses designated in MaineStreet as Remote. These courses, originally designed to be taught on campus and designated as UM Off-site in MaineStreet, have been adapted for delivery entirely at a distance. Class meetings may be held synchronously via streaming (on Zoom or another platform), recorded and posted for later viewing, and/or replaced by other learning activities.

In advance of the Fall 2020 semester, faculty members in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences were given the chance to reflect on the challenges, benefits, and practical components of remote learning. Here are some of their responses.

Kirsten Jacobson, Chair, Department of Philosophy

When the University of Maine switched to emergency remote delivery this past spring, many philosophy faculty and students were concerned that we would lose the rich conversational environment facilitated by face-to-face instruction. We were, however, pleased to discover a variety of approaches that helped to bring our new virtual classrooms to life. Some instructors held synchronous Zoom discussions and utilized breakout rooms for small group discussions; others developed online “journaling” assignments; many created group projects to promote students working together to create co-authored presentations or documents; a number created study groups or study cafes; and all held Zoom office hours. These responses were formed quickly, but successfully so. Professors found that some students who had been reticent to speak up in a physical classroom discovered their voices more fully via discussion boards; students also exercised their philosophical writing skills more regularly owing to necessary shifts toward virtual communications; and new connections were made among students as shifts away from physical seating led to different arrangements for group work. As a department, we were pleased to hear many of our students speak highly of the level of engagement that their philosophy courses continued to hold for them after the move to remote delivery this past spring.

When the University of Maine switched to emergency remote delivery this past spring, many philosophy faculty and students were concerned that we would lose the rich conversational environment facilitated by face-to-face instruction. We were, however, pleased to discover a variety of approaches that helped to bring our new virtual classrooms to life. Some instructors held synchronous Zoom discussions and utilized breakout rooms for small group discussions; others developed online “journaling” assignments; many created group projects to promote students working together to create co-authored presentations or documents; a number created study groups or study cafes; and all held Zoom office hours. These responses were formed quickly, but successfully so. Professors found that some students who had been reticent to speak up in a physical classroom discovered their voices more fully via discussion boards; students also exercised their philosophical writing skills more regularly owing to necessary shifts toward virtual communications; and new connections were made among students as shifts away from physical seating led to different arrangements for group work. As a department, we were pleased to hear many of our students speak highly of the level of engagement that their philosophy courses continued to hold for them after the move to remote delivery this past spring.

As we head into the fall semester, we are anticipating that all philosophy courses will be delivered remotely. We are thankful that we have the great advantage of being able to prepare in advance for this. Philosophy faculty members are hard at work adapting the content and format of their courses to maximize their effectiveness for remote delivery. We are experimenting with activities such as using shared virtual bulletin boards; recorded video-chain conversations; “pencasts” to layer audio atop visual materials ranging from annotated readings to PowerPoint presentations; semester-long work cohorts within courses; possibilities for student design input within some course modules, etc.,. We are also planning a number of extracurricular activities to connect our students outside of the classroom—including student-led discussion groups, philosophy forest walks, philosophy outreach opportunities, online movie nights, and philosophy “labs” where students can work through questions together as well as giving and receiving writing feedback. Using departmental gift funds, we are hoping to hire some of our majors to lead or co-lead a number of these projects as a means of 1) providing leadership opportunities and jobs for a few students and 2) providing inspiring peer-led activities for all of our majors and minors. Thus, in spite of our historical preference for face-to-face courses, the philosophy department genuinely feels enthusiastic about the opportunities that these new undertakings will offer us and our students. Sometimes a challenge or obstacle provides invigorating opportunities for reexamination and growth!

Daniel H. Sandweiss, Professor of Anthropology and Quaternary and Climate Studies

Class enrollment and students’ prior experiences in a discipline are important factors in pedagogy, in remote learning no less than in in-person contexts. An introductory course, Anthropology 101 in its remote form will be delivered asynchronously. Based on research that suggests videos longer than 8-10 minutes are less effective for students in terms of attention and knowledge retention, and that iterative exercises at regular intervals help learning stick, each “class” of ANT101 will consist of modules, most shorter than 10 minutes and each followed by an ungraded “knowledge check”—a few multiple choice, true/false, matching, fill in the blank, and/or pick-from-a-list questions about the module that students just viewed. Occasionally there will be optional online group projects.

Class enrollment and students’ prior experiences in a discipline are important factors in pedagogy, in remote learning no less than in in-person contexts. An introductory course, Anthropology 101 in its remote form will be delivered asynchronously. Based on research that suggests videos longer than 8-10 minutes are less effective for students in terms of attention and knowledge retention, and that iterative exercises at regular intervals help learning stick, each “class” of ANT101 will consist of modules, most shorter than 10 minutes and each followed by an ungraded “knowledge check”—a few multiple choice, true/false, matching, fill in the blank, and/or pick-from-a-list questions about the module that students just viewed. Occasionally there will be optional online group projects.

Each class ends with one question that carries a small amount of extra credit, and there will be a virtual tour of the Hudson Museum for additional extra credit, with an option of safe, small group live tours for students who are comfortable with that. Assessments will include open book assignments, each with 20 questions based on readings in the textbook; and four exams, each with 50 multiple choice questions drawn mainly from the recorded modules. Exams are not cumulative. Students will have 50 minutes to do each exam once they start, but can (in the interest of flexibility that remote learning allows over scheduled in-person classes) start at any time over a two-day period.

Each Monday during the regularly scheduled time for each section, the professor will hold an open “Archaeology Zoom Chat” in which students can ask any questions they have about the course material or about archaeology in general and can have a group discussion. Students can also request one-on-one meetings with the professor or the TA. All the videos have closed captions, so students can follow along aurally and/or in writing. This simple accomodation has clear benefits for those who may be hearing impaired, but is also a choice that has broader benefits—for the many students, for example, who choose to work at different paces by watching videos at 1.5x or double speed.

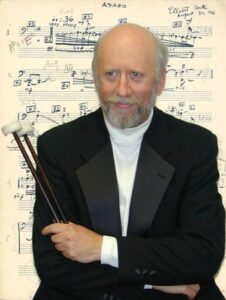

Stuart Marrs, Professor, Division of Music

Artists in many disciplines and genres have found that restriction of parameters stimulates creativity! That principle has become abundantly clear in our faculty’s response to teaching during a period of social distancing. In the process of thinking about everything anew, insights and improvements spring to the forefront. So, far from handicapping our teaching mission, this situation will make the entire enterprise better than what it was before.

Artists in many disciplines and genres have found that restriction of parameters stimulates creativity! That principle has become abundantly clear in our faculty’s response to teaching during a period of social distancing. In the process of thinking about everything anew, insights and improvements spring to the forefront. So, far from handicapping our teaching mission, this situation will make the entire enterprise better than what it was before.

I teach a broad variety of course material, from introductory music theory (Fundamentals of Music), to Music History, to a graduate course in Music Research, and finally applied music lessons in Percussion. With the exception of the Fundamentals of Music course, which I have been teaching asynchronously online for years and which has been polished and improved by an editorial team over a 50-year period, I am approaching all my courses with fresh eyes, ears, and mind.

For my graduate course in Music Research, I am taking advantage of technology to deliver much richer and more robust lecture content than I did during the live lectures. I am now able to add relevant graphics, video, and sound to the presentation in a more effective and engaging way. Now it is more like a series of short documentary movies than video recordings of a professor standing in front of a class. Combining that content delivery with the effective learning environment of Brightspace for additional materials, quizzes, sharing, and assignment areas is producing a more effective, clearer, and focused course. Of course, Zoom provides a means for real-time interaction as well. Scheduling this course was always a challenge in the past because most of my graduate students were working full-time. Now each student will be able to fit it into their own unique schedule. This is a huge improvement.

For my undergraduate students in history and applied lessons, Brightspace provides a simple and clear learning environment. I have introduced evaluation rubrics, familiar to students from their high school years, for many aspects of my courses. Whether it is for responding to academic writing or working with my percussion students on their practicing and performance, the rubrics provide clear guidance on expectations and outcomes. Zoom brings us all together in real time, and the recorded live sessions are always available for reference or for those who have had to miss a lecture. In my History syllabus, I suggest that students can choose to not take notes during the live lecture, but rather listen as if listening to a storyteller. Then go back to the recording to take and organize their lecture notes.

I am excited to move forward with some of these new (to me) teaching/learning modalities and it is inspiring to witness a broad evolution in teaching culture at our university. It is this collective creative response to our new parameters that in the end benefits our students of today and tomorrow.

Todd Zoroya, Lecturer, Department of Mathematics and Statistics

I teach a regular online statistics course, and was also teaching a Pre-Calculus class that went remote in the Spring 2020 term. President Joan Ferrini-Mundy actually sat in my Pre-Calculus lecture classes on a regular basis before we went to emergency remote learning. She sat in a couple of times as well after going remote, through Zoom. Though I benefitted from past experience teaching online, I tried to make my remote class as similar as possible to my normal active learning approach in face to face settings. President Ferrini-Mundy commented to me that the structure and style of the remotely delivered portion of the course was very similar to how the class was functioning before the pandemic.

I teach a regular online statistics course, and was also teaching a Pre-Calculus class that went remote in the Spring 2020 term. President Joan Ferrini-Mundy actually sat in my Pre-Calculus lecture classes on a regular basis before we went to emergency remote learning. She sat in a couple of times as well after going remote, through Zoom. Though I benefitted from past experience teaching online, I tried to make my remote class as similar as possible to my normal active learning approach in face to face settings. President Ferrini-Mundy commented to me that the structure and style of the remotely delivered portion of the course was very similar to how the class was functioning before the pandemic.

In terms of my regular online course, STS 232 (Principles of Statistical Inference, enrollment of approximately 50 students) is set up so that students read short excerpts, watch short videos, work through step by step examples, and do computer simulations. This way, students have numerous ways to work through the material. When completing homework problems, students have access to examples and step-by-step walk-throughs; the course is designed in such a way that they can send me a quick Ask Instructor question via our learning management system, use an on-demand tutoring service, or meet with my TA or me online via Zoom.

For my in-person MAT 122 (Pre-Calculus, enrollment of 75 students) course that went remote in the Spring, we continued to meet during our regular Monday/Wednesday/Friday class times using Zoom. Students worked through investigations in groups, using breakout rooms. As students are working through the investigations, my Teaching Assistants (TAs), Maine Learning Assistants (MLAs), and I popped into the breakout rooms to help guide the investigations, answer questions, and deal with any misconceptions. During Tuesday/Thursday recitations, students gathered in smaller groups with TAs and MLAs using Zoom to work through problem sets and deepen their understanding of concepts covered in class. The TAs, MLAs, and I offered regular office hours using Zoom, as well as setting up individual appointments as needed.

Hollie Adams, Assistant Professor, Department of English

For six weeks from mid-May until late June, I taught a fully remote graduate-level literature class. Senior undergraduate and graduate literature seminars are typically discussion-based with very little lecturing by the professor. The professor instead acts as a facilitator and students are expected to come to class with their own insights and discussion questions. Knowledge is generated through the students’ own discoveries, research, and collaboration with their peers. For these reasons, I felt that the learning needed to happen primarily synchronously and that I needed to provide a platform for students to be able to interact with each other in real time. We were originally scheduled to meet on campus for 3.5 hours twice weekly. Instead we met via Zoom for 2.5 hours twice per week—as that seemed to be the maximum length that students were able to stay focused on Zoom—and I assigned two hours of asynchronous learning activities per week to make up the time difference; these activities included watching pre-recorded lecture videos, posting to discussion board, and peer workshopping.

For six weeks from mid-May until late June, I taught a fully remote graduate-level literature class. Senior undergraduate and graduate literature seminars are typically discussion-based with very little lecturing by the professor. The professor instead acts as a facilitator and students are expected to come to class with their own insights and discussion questions. Knowledge is generated through the students’ own discoveries, research, and collaboration with their peers. For these reasons, I felt that the learning needed to happen primarily synchronously and that I needed to provide a platform for students to be able to interact with each other in real time. We were originally scheduled to meet on campus for 3.5 hours twice weekly. Instead we met via Zoom for 2.5 hours twice per week—as that seemed to be the maximum length that students were able to stay focused on Zoom—and I assigned two hours of asynchronous learning activities per week to make up the time difference; these activities included watching pre-recorded lecture videos, posting to discussion board, and peer workshopping.

One of the course’s assignments was to deliver a conference-style paper. Had we been meeting in a classroom, students would have delivered their conference papers in-person during the allotted 3.5 hours of class time. However, instead of having students deliver their papers in real time via Zoom, I had students pre-record their presentations and upload them to our course website in advance of our class meeting. This decision had several benefits: the presenters were able to edit and re-record their videos and could deliver the presentation without a “live” audience, reducing some of the stress and anxiety associated with presentations; students were able to pause, rewind, and re-watch their peers’ presentations as many times as needed to ensure full comprehension; and we all had a day with which to think about the presentation, gather our thoughts, and generate discussion questions rather than having to respond to the presentation immediately.

Overall, the fully remote model was a success. I had twelve students, and I had perfect attendance for all classes over six weeks. The discussion was lively, robust, and productive. Students came to the Zoom meetings prepared to discuss the week’s reading materials and appeared to be fully engaged during our conversations. The students who tended to be relatively quiet during the synchronous Zoom sessions contributed meaningfully during the asynchronous activities. The final essays were strong and demonstrated that real learning had taken place. I am scheduled to teach another graduate literature seminar in the fall semester and plan to use the same model: we will meet synchronously via Zoom for 2 hours per week with the other hour of class time devoted to asynchronous learning activities.

I am also teaching two undergraduate Creative Writing classes in the fall semester that will both be taught remotely: Intro to Creative Writing and Writing Fiction. Undergraduate students naturally have different challenges and different needs than graduate students, and so I will be using a hybrid-model of synchronous and asynchronous teaching, while making additional accommodations for students who might not be able to attend every Zoom meeting for whatever reason (e.g., connectivity issues, childcare duties, work responsibilities). Both classes were originally scheduled to meet in-person on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Now on Tuesdays, students will be asked to complete asynchronous tasks (which do not necessarily need to be completed during our originally-scheduled class time, to allow students some flexibility with their weekly schedules). These tasks will include watching my pre-recorded lecture videos, completing writing activities, posting to the course discussion board, and workshopping their peers’ writing. On these Tuesdays, I will be available during our originally scheduled class time; students will be able to Zoom with me one-on-one for tutorials, to ask questions, and to receive feedback on work in-progress. On Thursdays, students will be asked to attend synchronous one-hour Zoom sessions during our regular class time. During these meetings, students will have the chance to discuss the week’s assigned readings, talk about the writing and editing process, and ask questions of me and each other.

During these Zoom meetings, I will also lead students in real-time writing and editing activities—for example, I will ask them to bring writing they worked on asynchronously to Thursday’s Zoom meeting where I will then have them engage with their own work, leading them through a series of activities that ask them to revise, rethink, and rewrite what they accomplished on their own time. I will also make use of the “break-out room” function in Zoom to put students into small 3-4-person groups, which I will then circulate among, to ensure that quieter students who may be uncomfortable speaking in a larger group are able to contribute to discussion and converse with their peers. Additionally, I hope to have guest writers Zoom in during our class time to discuss the writing process and answer questions.

To accommodate students who are unable to attend the synchronous Thursday Zoom sessions, I will make instructions for the writing/editing activities available; there will also be discussion board forums open for each of the week’s readings and discussion topics where students will be able to post their insights, comments, and questions as well as respond to their peers’ ideas. Our synchronous Zoom sessions may also be recorded and made available for students who were unable to attend the live meetings—especially in the case of a visit from a guest writer.

Philip Edelman, Assistant Professor, Division of Music

One of the exciting lessons that I learned during our abrupt switch to online learning last semester was the importance of connection. In my remote courses, we will do a lot of reflecting together, learning from and with each other, and a lot of one-on-one zoom meetings to make sure that students understand the course material. We will also connect in small groups so that students in practical pedagogy classes can make transfers of what we are learning remotely to their eventual teaching positions. The most rewarding aspect of our remote learning last semester was the sense of community and connection I had with my students. They were eager to meet individually to discuss triumphs and fears, and my goal is to be just as accessible to them this semester as I was last semester, if not more. We will be using this opportunity to reflect on the core of our subject matter: What is essential? Why is it necessary? How can we teach these concepts even when we are in situations where playing instruments is not possible? I am looking forward to our time together immensely.

One of the exciting lessons that I learned during our abrupt switch to online learning last semester was the importance of connection. In my remote courses, we will do a lot of reflecting together, learning from and with each other, and a lot of one-on-one zoom meetings to make sure that students understand the course material. We will also connect in small groups so that students in practical pedagogy classes can make transfers of what we are learning remotely to their eventual teaching positions. The most rewarding aspect of our remote learning last semester was the sense of community and connection I had with my students. They were eager to meet individually to discuss triumphs and fears, and my goal is to be just as accessible to them this semester as I was last semester, if not more. We will be using this opportunity to reflect on the core of our subject matter: What is essential? Why is it necessary? How can we teach these concepts even when we are in situations where playing instruments is not possible? I am looking forward to our time together immensely.Jen Tyne, Lecturer, Department of Mathematics and Statistics

My remote calculus course will be a combination of synchronous and asynchronous learning. Students will watch short videos that I create on my iPad, as well as take short “video quizzes” after each sections’ videos. These quizzes will be conceptual in nature, and will ensure that students understand the “big picture” of the video. Then, students will meet in recitations of 25 students with their graduate TA (teaching assistant), where students will get to practice the concepts from the video, working on problems sets that are available through a course pack (purchased in the bookstore). The true learning in calculus takes place when students work on problems, with assistance from other students and TAs. In addition to available zoom help hours where students can get one-on-one or small group help from me, I will also meet with all students together once per week via zoom, allowing students to ask me questions from the week’s material, and also allowing me the opportunity to go over additional problems as needed to complement the videos and recitations.

My remote calculus course will be a combination of synchronous and asynchronous learning. Students will watch short videos that I create on my iPad, as well as take short “video quizzes” after each sections’ videos. These quizzes will be conceptual in nature, and will ensure that students understand the “big picture” of the video. Then, students will meet in recitations of 25 students with their graduate TA (teaching assistant), where students will get to practice the concepts from the video, working on problems sets that are available through a course pack (purchased in the bookstore). The true learning in calculus takes place when students work on problems, with assistance from other students and TAs. In addition to available zoom help hours where students can get one-on-one or small group help from me, I will also meet with all students together once per week via zoom, allowing students to ask me questions from the week’s material, and also allowing me the opportunity to go over additional problems as needed to complement the videos and recitations.

Ayesha Maliwal Bundy, Lecturer, Department of Mathematics and Statistics

Research has shown the importance of experiential learning in creating meaningful educational experience for students. To facilitate this active learning pedagogy, I followed a “flipped classroom” approach during the spring semester while teaching MAT 116: Introduction to Calculus. Under this model, students were introduced to the concepts before they came to class through videos that were created with the help of Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning (CITL) on campus. This allowed students to take their time learning the concepts by slowing down the videos, taking notes, and revisiting them over and over. The time in class was then for students to practice and apply the concepts, working together in groups. The presence of Maine Learning Assistants (MLAs) assured the availability of lots of help for students, both within and outside the classroom.

Research has shown the importance of experiential learning in creating meaningful educational experience for students. To facilitate this active learning pedagogy, I followed a “flipped classroom” approach during the spring semester while teaching MAT 116: Introduction to Calculus. Under this model, students were introduced to the concepts before they came to class through videos that were created with the help of Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning (CITL) on campus. This allowed students to take their time learning the concepts by slowing down the videos, taking notes, and revisiting them over and over. The time in class was then for students to practice and apply the concepts, working together in groups. The presence of Maine Learning Assistants (MLAs) assured the availability of lots of help for students, both within and outside the classroom.

The structure of this course prevented the pandemic from disrupting the flow of learning. Even when we transitioned to remote teaching, students continued to watch videos before coming to class. Through numerous examples and use of polls, it was easy to engage students in discussion during the virtual class. The Zoom feature to send students into virtual “breakout rooms” facilitated group work where students brainstormed problems together while the MLAs and I moved between different groups, answering questions and scaffolding student learning.

Moreover, after transitioning to remote teaching, I placed even greater emphasis on helping students feel grounded and connected in this new setting. I was aware, through lots of conversations with students, that they needed more structure and support to help them navigate through the uncertainty. Daily emails provided a gentle reminder so students could plan their learning, the Zoom class times created that community where they could clarify their doubts and work together, numerous help sessions created a space for them to seek support (now the instructors and learning assistants were collectively able to offer over 20 hours of help per week outside the classroom and since all sessions were held over Zoom, we could extend our availability to evenings and weekends as well), and finally, the openness to feedback and resolution of problems in real time provided the comfort that they were not alone.

In my view, remote teaching is not a necessary evil; rather, this experience has opened up my vision and understanding to how much more teaching can be beyond the classroom walls. This Fall semester, I will be again teaching the course remotely. Over the summer, I have been working on making the course more inclusive and accessible, more meaningful and applicable, more engaging and interactive. This includes rewriting the set of worksheets with more practice problems for students to work on, including more examples of real-life events and applications, providing clear captioning on videos, creating online discussion forums for students, redesigning assessments and planning a clear structure for the students with lots of support systems in place.

Though the pandemic has been a devastating blow to all of us, I personally think it will have a positive long-term impact on the quality of education. Across the globe, educators are converging and trying to find out how to not only make this work but to make it better than before. We are rethinking how we teach and what we teach. We are analyzing our teaching approaches and finding ways to make learning more meaningful, during and beyond covid-19. We all know that the world was changing even before the pandemic. With technology and AI at its current stage of advancement, there was a need to redefine our goals, methods and desired learning outcomes. Though we all wish there was a better reason for us to push for change, now that we are here, we cannot turn back. We cannot return to the world before the pandemic and should instead strive to reach a better place. I believe that the efforts of higher education to redefine teaching and learning will prove to be a big step in that direction.