Glacier Mini Lessons

More lessons and lesson components will be added throughout 2017.

Glacial Flow

If you’ve ever pushed on ice, it probably slipped, or if you pushed really hard, it cracked. Ice sheets and glaciers are very large masses of ice – the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica have thicknesses that are about 30x the height of the Statue of Liberty and Big Ben, 10x that of the Eiffel Tower, and over 3x that of the tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa.

Glaciers flow under their own weight, much like pancake batter will spread out from the spot where it is poured. You can make your own glacier!

Ice in glaciers and ice sheets usually flows too slowly to observe in a day (kind of like watching grass grow). One of the fastest glaciers is Jakobshavn Isbrae in Greenland; in 2012 it moved 10.5 miles (17 kilometers) in a year (Joughin et al. 2014, The Cryosphere). This is the same glacier and year where Chasing Ice filmed a huge chunk of the glacier breaking off.

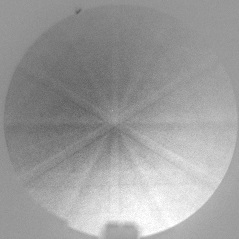

Crystallographic Orientation

When you make ice cubes, each is a single crystal. Glaciers and ice sheets are made of many crystals because they form from snow that compacts and grows together. Each ice crystal has one “soft” orientation – when you push on it in that orientation, it deforms much more readily than any other direction you push on it. If all the ice crystals in the glacier are lined up so that their soft orientation is pointing the same way, it will be easier to make the whole glacier flow quickly. If the crystals are oriented all different directions, then the crystals get in a traffic jam and the glacier does not flow as readily.

We can measure the orientation of ice crystals (called “crystallographic orientation fabric”) in a sample of a glacier with a scanning electron microscope (SEM). We have outfitted the SEM at the University of Maine School of Earth and Climate Science with a special holder that keeps the ice cold while we analyze it. We are one of a small number of labs in the world that has this capability.