Science with Attitude

By David Sims

After graduating from St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont in 2012 with a degree in biology, Connecticut native Emma Fox became an AmeriCorps Environmental Educator at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine.

Her AmeriCorps work hooked her up with a consortium of stakeholders known as the Frenchman Bay Partners (FBP) that since 2010 has worked to ensure Frenchman Bay—bounded on the east by the Schoodic Peninsula and Mount Desert Island on the west—is ecologically, economically and socially healthy and resilient in the face of future challenges.

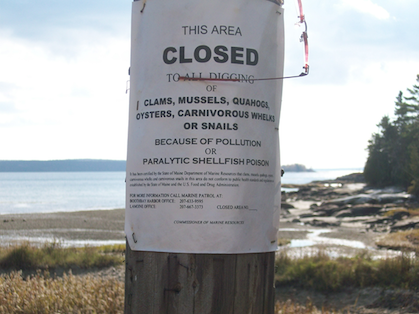

A contemporary effort of FBP is the 610 Project, which is aimed at opening 610 acres of closed mudflats. Fox’s initial work in Frenchman Bay was focused on the mudflats that are valuable to Maine’s economy, but also prone to bacterial pollution and, thus, closure. That valuation work began to steer Fox from her biology background to more of an economics and social science focus, all of which eventually landed her at UMaine and the Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions as part of the New England Sustainability Consortium (NEST) on an unexpected path towards a master’s degree.

“I had not planned to pursue a master’s degree, Fox says, “but the Frenchman Bay Partners research got me interested in economics and social science and also introduced me to Dr. Bridie McGreavy, who at the time was working with the Partners as part of her dissertation research.” (McGreavy, now an assistant professor in the UMaine Department of Communication and Journalism and member of the Mitchell Center, coordinates the 610 Project.)

That connection brought Fox to McGreavy’s dissertation defense at the Mitchell Center where McGreavy “was kind enough to announce ‘There’s someone here looking to be a master’s student and you should pick her up!’” recalls Fox. One thing led to another and Fox was introduced to NEST researcher Kathleen Bell of the School of Economics, who in turn connected Fox with Caroline Noblet, also of NEST, the School of Economics and the Mitchell Center, and now Fox’s advisor.

One component of her master’s thesis work has involved gauging how FBP members and stakeholders understand and value the so-called “ecosystem services” provided by the surrounding environment—including water filtration by soils.

Forest soils are superb at filtering water and, for example, had regions of the Catskills and Adirondack mountains not been preserved more than a century ago New York City would not have a plentiful supply of good water—that ecosystem service would have to be replaced by enormously expensive water treatment plants. Closer to home, coastal wetlands function as natural water filtration systems thereby helping to protect shellfish habitat from pollution and bacterial contamination.

Frenchman Bay ecosystem services

“Ecosystem services is a new focus the Partners has adopted, which is what got me interested in looking at it for my thesis work,” Fox says. “They did a series of workshops where they brought people in the Frenchman Bay region together to talk about what ecosystem services are.

Workshop participants included a diverse group from the Bar Harbor and Hancock business communities. “People come to Bar Harbor because of natural resources in the area—Acadia is a huge draw—and so they benefit directly or indirectly from the availability of these resources and the services that Frenchman Bay provides,” Fox notes.

Workshop participants included a diverse group from the Bar Harbor and Hancock business communities. “People come to Bar Harbor because of natural resources in the area—Acadia is a huge draw—and so they benefit directly or indirectly from the availability of these resources and the services that Frenchman Bay provides,” Fox notes.

“My research explores the Partners’ use of Ecosystem Service Values workshops as a means to engage people, so I’ve been following up with participants through interviews to see what was challenging to them, what they really know about ecosystem services, and if the workshops changed their perspectives,” Fox says.

A separate but related part of Fox’s thesis work has involved gauging public attitudes towards coastal water quality and the public’s willingness to pay for improvements in water quality.

Poor coastal water quality is both a public and environmental health concern. Contributors to poor water quality come from natural (flood events) and human (bacteria from pet waste, leaking septic systems, wastewater overflow, or sewer outfall) sources. Knowing what drives human behaviors on the coast can help managers target efforts and messages to mitigate harmful behavior, encourage healthy behavior, and effectively inform those who live, work, and play on the coast about possible threats to the health of the coastal environment.

“The purpose of this aspect of my master’s work is to identify attitudes residents may have about coastal water quality and use them to help understand citizen support for water quality improvement, and think strategically about messaging as a means to change citizen behavior,” Fox explains.

This work, which was done in parallel to the FBP work Fox did, was conducted as part of the National Science Foundation-funded NEST Safe Beaches and Shellfish project and carried out via a mixed-method pilot mail/online survey sent to coastal residents in Maine and New Hampshire.

“In our surveys, we asked about resident willingness to pay an increase in monthly sewer/water/septic fees to support a hypothetical Coastal Water Quality Improvement Program,” Fox says. “From the survey work, with data on attitudes and valuation in hand, we can go back to state agency partners at the Maine Healthy Beaches Program, the Maine Coastal Program, and the Department of Marine Resources and say, ‘Here is a way to help gauge citizen support for coastal zone programs.’”

“In our surveys, we asked about resident willingness to pay an increase in monthly sewer/water/septic fees to support a hypothetical Coastal Water Quality Improvement Program,” Fox says. “From the survey work, with data on attitudes and valuation in hand, we can go back to state agency partners at the Maine Healthy Beaches Program, the Maine Coastal Program, and the Department of Marine Resources and say, ‘Here is a way to help gauge citizen support for coastal zone programs.’”

Additionally, Fox adds, coastal managers can use the attitudinal data as a way to think about framing information for citizens on small things they can do to keep the coast clean. For instance, she says, “We know from our data analysis that a resident’s sense of personal responsibility for improving coastal water quality is an important factor in his or her choice to support a coastal water quality program. So, for state agencies, making the connection between dog waste or leaky septic systems and clam flats closed to harvest due to bacterial pollution explicit for citizens is a way to use those attitudes as a way to leverage change.”

Fox intends to continue her valuation work with the Frenchman Bay Partners, of which she is a member, and at the end of May accepted a Ph.D. research assistantship with the NEST Future of Dams project.

“I’m most interested in what’s happening on the coast and on helping to solve real-world problems—what can be done in coastal communities to improve people’s lives.” She adds, “I feel very strongly about serving Maine’s coastal communities and, in addition to my continued work with the Partners, the Future of Dams project will allow me to do just that.”

“…all of the work I’ve been a part of is focused on the ultimate question of sustainability… And I’ve been fortunate that the whole Mitchell Center NEST project has been very applied and very tuned into stakeholder needs throughout.” —Emma Fox

The NEST Safe Beaches and Shellfish Project paved the way to her future academic endeavors and, she says, really opened her eyes with respect to the opportunities and unique challenges with collaborative, cross-institutional research partnerships.

“I think that all of the work I’ve been a part of is focused on the ultimate question of sustainability. The Partners are thinking about a sustainable future for Frenchman Bay and how everyone can benefit from the bay’s resources moving into the future. And I’ve been fortunate that the whole Mitchell Center NEST project has been very applied and cross-disciplinary and very tuned into stakeholder needs throughout. That’s really important. I’m looking forward to more collaborative work in the future.”