UMaine project will livestream total solar eclipse from the stratosphere

When Noah Lambert of Bar Harbor enrolled at the University of Maine, launching a giant balloon 90,000 feet in the air to livestream a total solar eclipse wasn’t an activity he imagined being able to do during his college career.

For the past year, Lambert and nine other undergraduate and graduate students have been designing and testing camera, data collection, control and tracking systems for an April 8 balloon launch by the UMaine High Altitude Ballooning program. These systems will be tethered to the balloon and a large parachute. The initiative is offering live video coverage of the event through YouTube, unique student training and support for national atmospheric research.

UMaine is among 75 institutions making up a combined 53 teams nationwide to participate in the Nationwide Eclipse Ballooning Project led by Montana State University (MSU). Some teams, including UMaine’s, will launch large balloon systems to livestream the eclipse and gather data on atmospheric phenomena. Others will send out radiosondes on small balloons every hour for 24 hours up to and during the eclipse, according to MSU.

The 53 teams are divided into nine pods, and the UMaine group is one of the pod leaders. Rick Eason, associate professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering, leads the UMaine team with support from Andy Sheaff, a lecturer and facilities support for the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

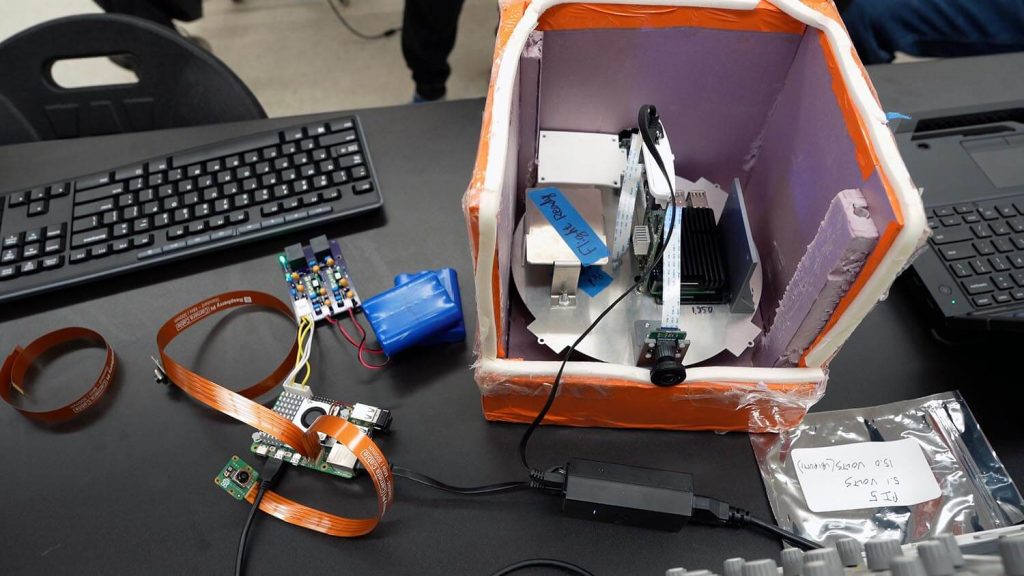

Lambert has been developing video system payloads — sets of standard and 360-degree cameras connected by wires and protected in boxes made of thick foam. He and his colleagues have also been testing payloads to ensure they don’t weigh down the large latex balloon, which is similar to a weather balloon.

Lambert has helped run workshops in Orono, Maryland and Minnesota, during which he and other students, as well as faculty nationwide, discuss strategies for effectively launching balloons during the eclipse and refining payloads for the camera, data, tracking and control systems. Many participants asked Lambert and his colleagues questions for assistance with troubleshooting, and they “became very quick experts on what we were doing,” he said.

“The job was a lot different than what I was expecting. It provided a lot of opportunities that I didn’t think was gonna happen,” Lambert said.

This is not the first total solar eclipse live-streamed by the UMaine High Altitude Ballooning Program. They previously participated in the MSU-led launch in 2017.

Preparing for April 8

UMaine’s balloon launch location on April 8 will be determined by wind direction and force, but it could occur anywhere in the Northeast. Leader of the UMaine team Eason said they will use predictive modeling to determine the optimal location.

The wind will steer the balloon. A ventilation system will fill the balloon with gas to lift it or release gas to drop it, which will slow the balloon’s ascent and eventually allow it to float. The vent system, provided by MSU and modified by the UMaine team, will be closed via remote control while the balloon is in the air, after which the balloon will ride the wind and float for up to 35 minutes with the intent to have it cross the eclipse path during totality.

While atmospheric forces will ultimately determine the balloon’s path, models can help the team predict where it will go and where they should establish a ground station, ideally located along the path of eclipse totality, for retrieval. Eason said the balloon will also be equipped with GPS technology to help the group track it down once it and all of its payloads return to the ground. Similar to the cameras, the GPS equipment will be packaged in foam boxes, which Sheaff says will protect them from cold temperatures in the sky and the impact of landing.

“When the payloads come down, the balloon is let go, and everything comes down on a parachute. The idea is the parachute deploys, and they come down nice and slow for a nice gentle landing,” Sheaff says.

The GPS data also will be shared with MSU researchers so they can investigate whether there is a connection between eclipses and low-frequency pressure waves that surround the atmosphere.

In preparation for the eclipse, Eason, Sheaff and their students are bench testing their equipment to ensure it will function properly and won’t weigh down the balloon. They are also testing the battery life of the equipment and its ability to communicate with computers and a satellite dish on the ground.

“There’s a lot of education for our students, who are diving into this project and just taking the lead on solving problems we don’t immediately know the answers to,” Eason said. “It’s not something that we’re just saying, ‘Oh, here’s a homework problem for you to do that we know the answer to, but you see if you can figure it out.’ These are real problems that provide real engineering experience.”

With over 135 launches since its inception in 2011, the UMaine High Altitude Ballooning Program has conducted research with college students and assisted K–12 classes with facilitating their own experiments at the edge of space. Learn more on the program’s website.

Contact: Marcus Wolf, 207.581.3721; marcus.wolf@maine.edu