World War II-era love letters unsealed after 50 years

“‘Bring him back to me, please’ That was my nightly request,” Frances Hartgen wrote. “The letters piled in my bureau drawer, eventually tied with ribbon and stacked away. For what or why I did not know.”

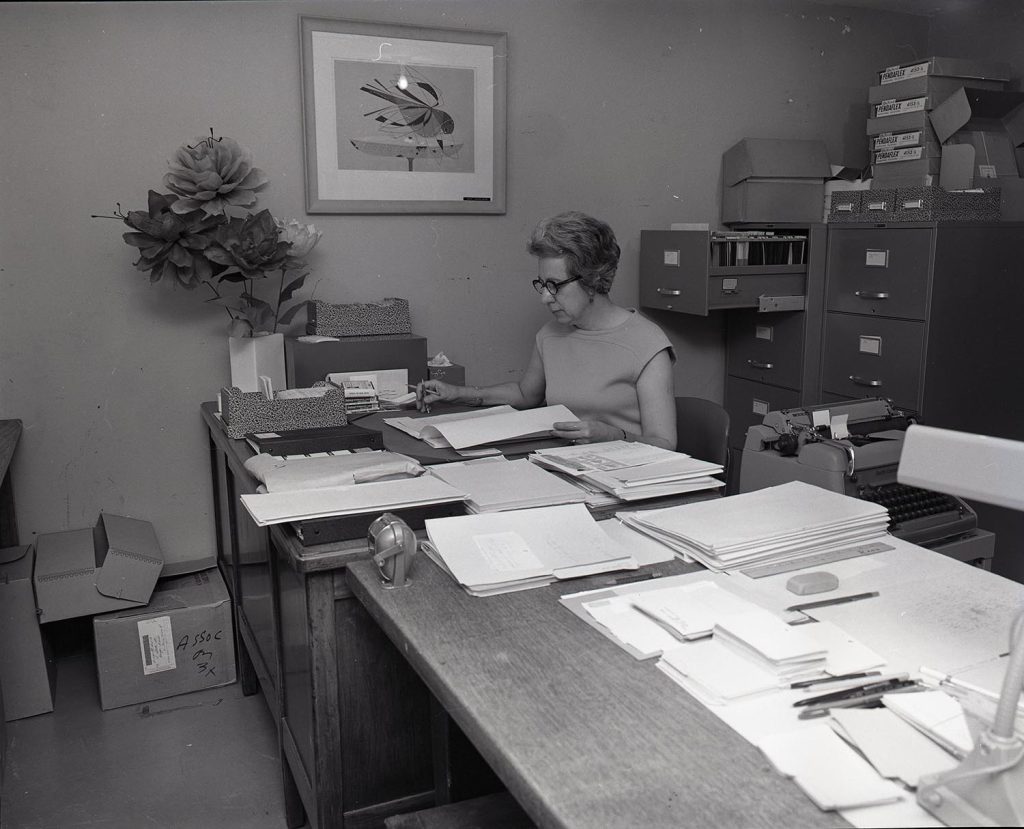

Hartgen recounted in her 2003 memoir, “For Vincent: A Love Story,” her days away from the man who would later become her husband. Written after Vincent Hartgen’s death, her memoir reads like the love letters she curated during her time as the head of Special Collections at the University of Maine’s Fogler Library in the 1970s. After 50 years in storage, Fogler has recently made one of those collections available to the public.

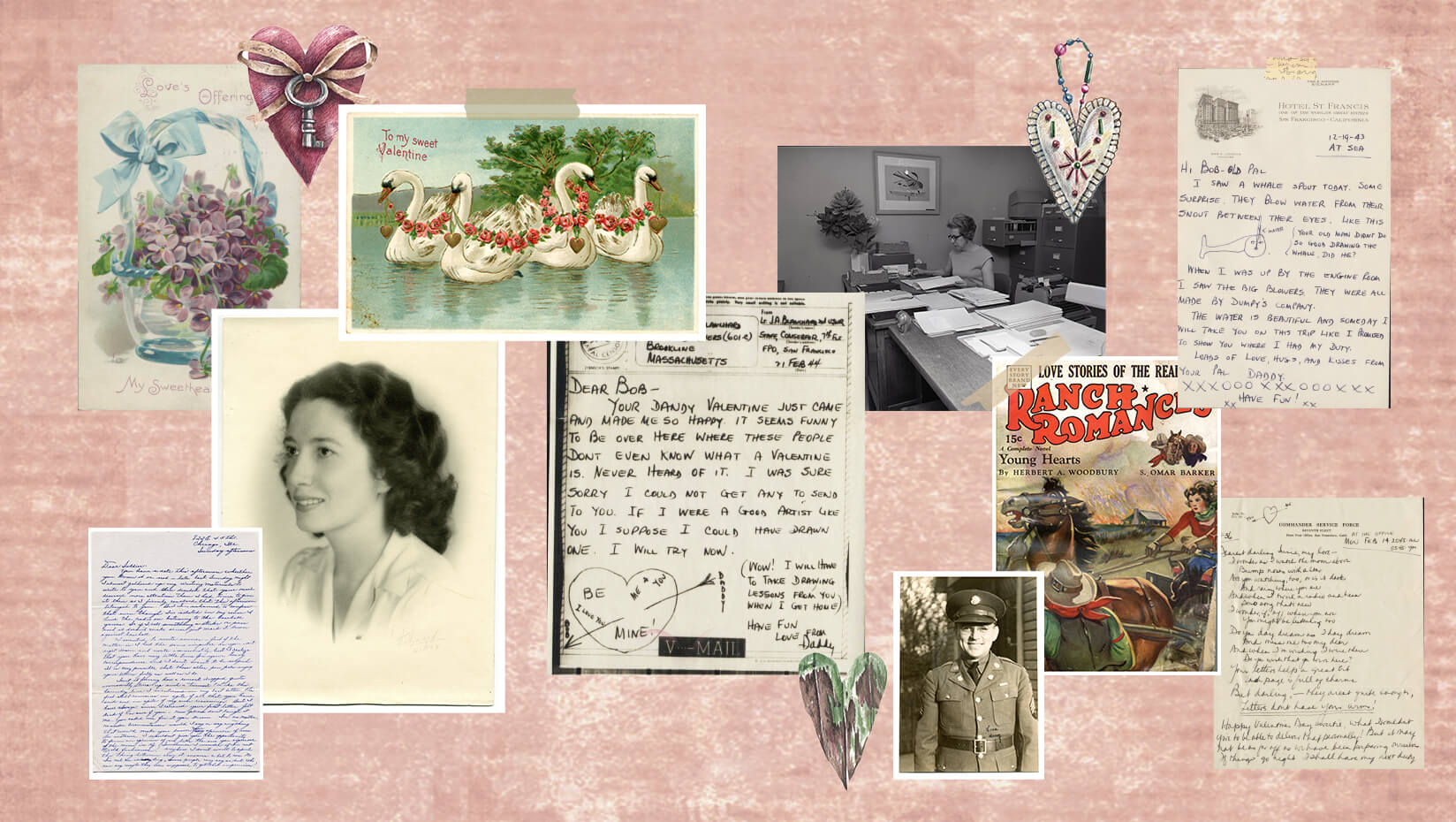

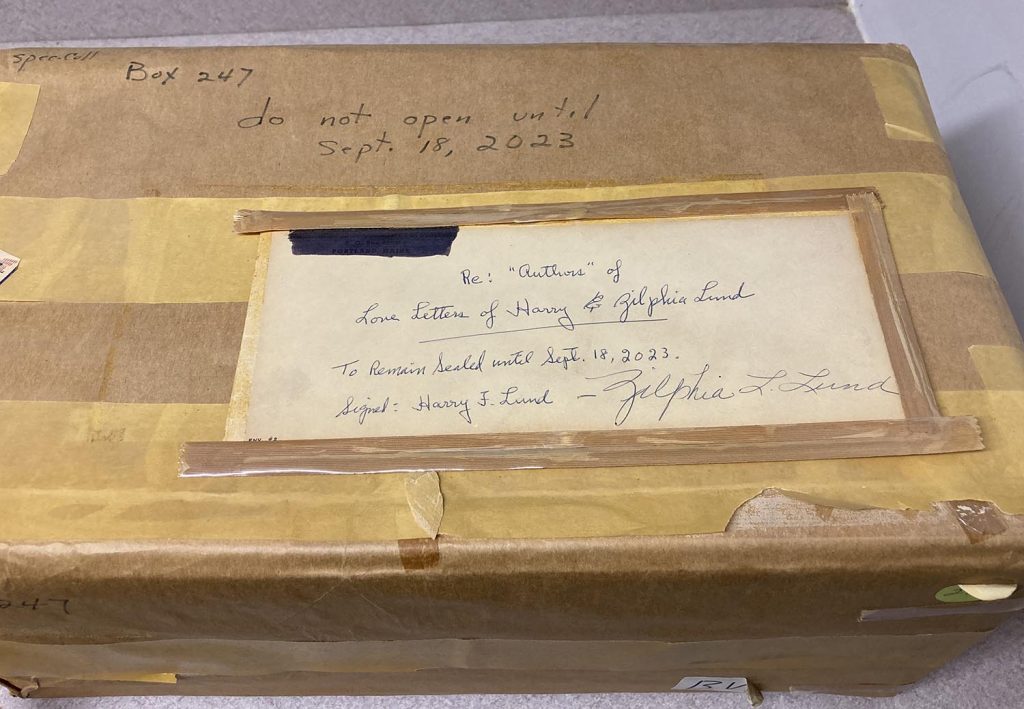

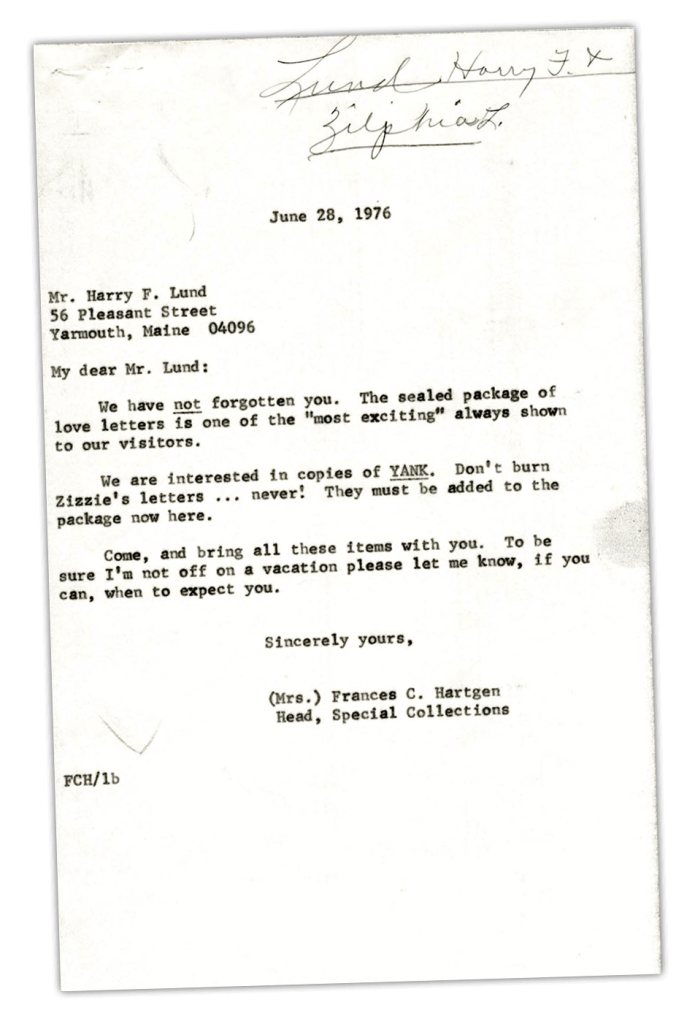

A televised plea from Hartgen on “A Time to Live” asked the public to donate love letters to the library. It caught favor with one couple who sent in 485 letters on one condition: they be kept sealed until Sept. 18, 2023, the date of their would-be 80th wedding anniversary. Those 485 letters from The Lund Collection contain exchanges made between the two during the World War II era.

A televised plea from Hartgen on “A Time to Live” asked the public to donate love letters to the library. It caught favor with one couple who sent in 485 letters on one condition: they be kept sealed until Sept. 18, 2023, the date of their would-be 80th wedding anniversary. Those 485 letters from The Lund Collection contain exchanges made between the two during the World War II era.

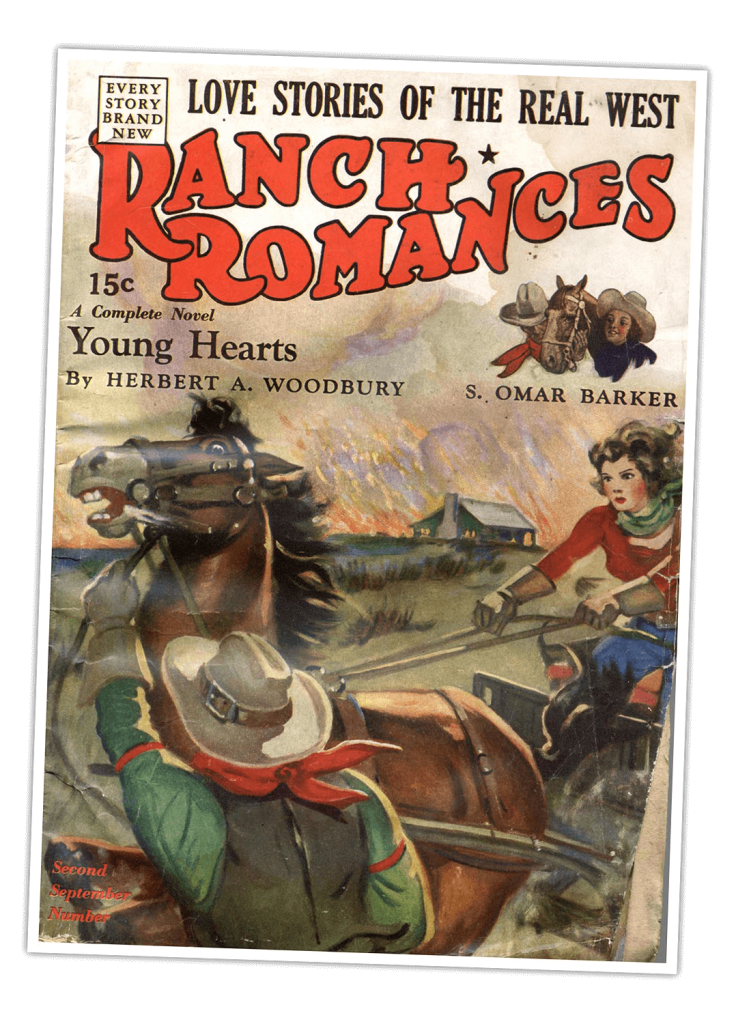

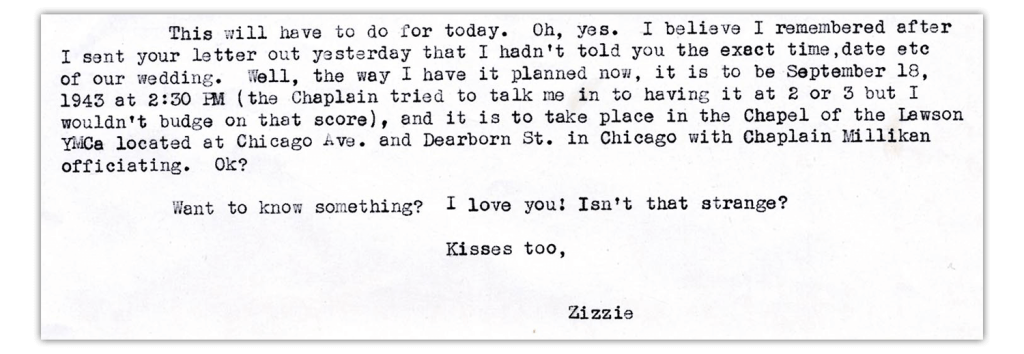

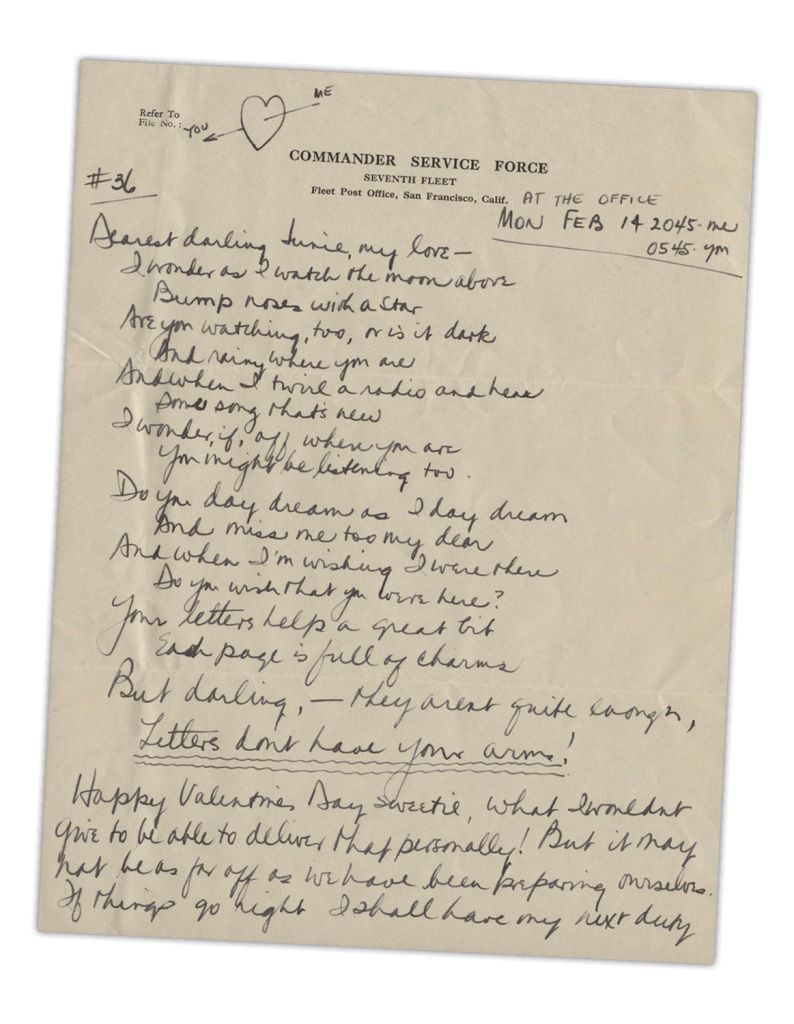

Harry Lund, a banker and soldier from Yarmouth, Maine and his future wife, Zilphia “Zizzie” Lund, began their relationship as pen pals in 1941. In “Ranch Romances,” a pulp magazine that mixed Western stories with romance novels, Harry submitted a letter to the editor asking for a friend to exchange letters with. “Circumstances have made me a lonesome duffer in my twenty-ninth year, and I have lots of time for writing,” his letter read. “I’d enjoy hearing from anyone near my own age.”

Zizzie answered this call. Many of the letters were sent by mail from Chicago where Zilphia worked to Fort Williams in Cape Elizabeth where Harry was stationed as a sergeant in the United States Army. The two eventually married in 1943.

“‘They were part of us,’ sais [sic] Mrs. Lund simply, ‘and we didn’t want to give them up. We felt, of course, that eventually we’d have to burn them since we didn’t want anyone else to read them — at least not while we’re alive,’” an old clipping from the Bangor Daily News read. “When she approached Mrs. Hartgen, Mrs. Lund asserted that the letters were not written by ‘name people. I am a housewife and my husband a bank clerk. We have lived a quiet married life in Maine, where our children were born.’

“‘History,’ Mrs. Hartgen replied, ‘Needs to be aware of the average person like you and me, what we did, felt and dreamed of doing. Those papers are just as important, in many ways more so, for study and research (as those of great personages).’

“‘The letters were written in business offices, in day – rooms, in guard rooms,’ said Harry. ‘But the message is there for our hearts to respond.’”

The promise to keep the box sealed was held, the contents of the love letters remaining a secret until the date the Lunds indicated they would like them released. Exchanges between the two, often handwritten but sometimes made with a typewriter, span about two decades, eventually including letters from Harvey Lund, their son (born in 1945), to his father.

The Lunds weren’t the only couple to donate their letters. Fogler Library’s Special Collection and Projects Department has the letters of many couples, including a large collection from James A. Blanchard II to his wife, June E. (Peterson) Blanchard, while he was stationed in the Pacific with the U.S. Navy.

Norma Stockwell, who lived in Bradford, and Paul Dewitt’s letters were also donated to the department. Similar to Harry Lund, Dewitt was stationed at Fort Williams and wrote to Stockwell often: “You should know how much I miss you dear. I think about you all of the time,” he wrote on April 8, 1942. On April 12, he received a reply, and while it’s filled with run-of-the-mill things (“Something is the trouble with my tooth it feels terrible everytime I move. Just as if it was bare. Ma says it may be an ulcer forming. Always something. Je mon cris! [sic]”) it also contains the heartache of missing one’s love: “Honest, dear, I miss you terrible [sic] and I just can’t go on any longer without seeing you,” she says.

Because Vincent Hartgen also served in the military and he and Frances spent much time apart as a result, it may be that Frances’ own experience influenced her interest in gathering love letters. Stephen and David Hartgen, the twin sons of Frances and Vincent, died in 2021, two of the last people likely to remember Frances and Vincent’s early relationship.

“The war years dragged on,” Frances’ memoir reads. “On the day Vincent was discharged he ran up the steps into the kitchen, stood there and peeled off his uniform, piece-by-piece, placing them in a pile at his feet …‘I’m going to bathe and by the time I come out of the bathroom that pile must be gone. I want never to see any part of it again,’” Frances remembers Vincent saying.“The coat was-warm and heavy [sic], The pants and shirt durable. No matter. His command was heeded. Off to the Salvation Army it all went. How many uniforms like that one found their way to this other army? Out of sight, but never out of mind.”

As for the love letters Frances mentions in her memoir, they are not part of this collection and may be lost to time. Her legacy instead lives on in those she collected from others.

“‘Their value to future generations,’ Mrs. Hartgen says, ‘is in expressing to them how we lived and felt about love experiences … No one can be assured how much material will be studied, viewed or read in the future, but it is my personal belief that the world will need to know how some of us expressed our courtship days in letters.”

The Lund Collection and other collections mentioned here can be viewed upon request in Special Collections at Fogler Library at the University of Maine.

Contact: Shelby Hartin, shelby.hartin@maine.edu