UMaine artists make life-size knight sculpture for use in classrooms across the state

On a bench inside a high-tech workshop lay a life-sized sculpture of a medieval knight. Crafted by University of Maine artists with 3D scanning and layered Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, coupled with traditional sculpture methods, the five-and-a-half foot warrior wore plate and mail armor and bore a sword and shield.

Though it appeared as if made from stone, the knight, which will soon galavant across Maine to teach children about life in medieval times, was made of a material one might not guess at first glance: poplar wood from Kings Mountain Hardwood in Orrington, Maine.

Sean Michael Taylor, a research engineer for UMaine’s Innovative Media Research and Commercialization (IMRC) Center, created the sculpture for History Live! North East, a nonprofit in Union, Maine which offers K–12 schools history lessons that involve showcasing and demonstrating various artifacts.

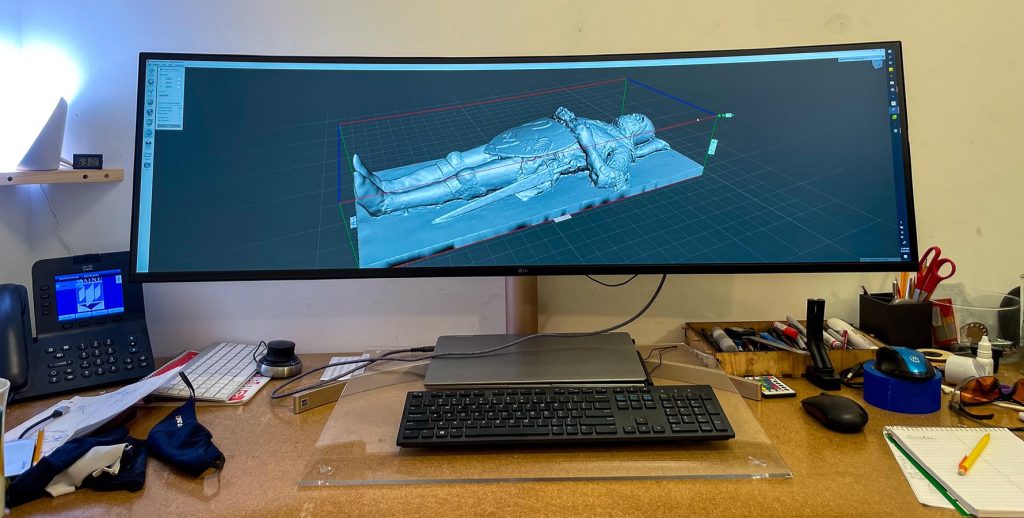

The two-and-a-half-year-long project began with Ian Donnelly, who has since graduated from UMaine, designing a 3D-model of the knight primarily through photogrammetry, a process that involved stitching together numerous photos of the founder of History Live! North East, Matt Blazek, dressed in armor.

From there, Taylor and his students, James LeBlanc, Ian Beckett, Mason Bloomquist and Maine Space Grant Consortium MERITS Program Intern Cooper Parlee refined the design and coded instructions for how IMRC technology could bring it to life. They shared a file with both with the CNC machine at the center, which milled the knight from a large block of wood in many two-inch layers over 24 hours of actual cutting time.

Taylor and his students then glued the layers together, scraped out excess wood and added details to the sculpture by referencing the 3D model in the software viewer and examining it from different angles.

Watch this YouTube video to learn more about the sculpture’s creation.

“My first thought when I got this request was ‘Oh, I can’t wait to do that! That sounds awesome!’ I’ve never done a life-sized sculpture with the CNC machine,” Taylor said. “I feel like I have a special place in the world, to be able to work on projects like these. To be creative is one of the best feelings I can imagine.”

A six-foot-long wooden panel is attached to the sculpture so it can be used to top off a tomb, said Blazek, also executive director and lead historical interpreter for History Live! North East. He plans to use it to showcase how warriors were memorialized in medieval times. This will complement other artifacts like weapons and armor that Blazek hopes will someday encompass a mobile, interactive exhibit.

“The collaboration with UMaine has been great. Everyone at the IMRC consistently kept me in the loop throughout the process,” Blazek said. “It’s one of the coolest projects I’ve ever worked on.”

As an artist, Taylor’s mission is to showcase the utility of art and to create works with practical applications that benefit society. He also researches the ways in which artists solve problems, methods that scientists, historians, engineers and other professionals could apply to their own work.

“I think problem solving is something we should focus on more, especially in higher education,” he said. “Creatives solving problems can benefit all fields.”

The sculpture not only offers educational benefits for K–12 students. Taylor himself used the crafting process as an opportunity to teach students how to use digital software and industrial equipment to create art. Some of his undergraduate and graduate students learned how to use new software, while others coded instructions for the CNC machine for the first time.

“I know that there’s a high probability that students are going to fail at their first attempts in creating something with the CNC machine, and I try to get them to push themselves past that,” he said. “In the second attempt, it’s funny how fast all of the good parts come back from the first attempt, but their composition is better. So that’s the creative design process we’re trying to push students to learn.”

Work at the IMRC is collaborative and interdisciplinary. Taylor said he teaches students who study art, intermedia and engineering. Industrial design, he said, is a form of art. While using engineering processes to create art can be difficult, it allows for unique creations to come to fruition.

“When all these different forces like art and science come together, that’s the creative process. Then when you add technology to that, it’s exponentially unfolding what art can be,” Taylor said.

Contact: Marcus Wolf, 207.581.3721; marcus.wolf@maine.edu