Vincent Weaver ‘demakes’ video games to teach about computer systems

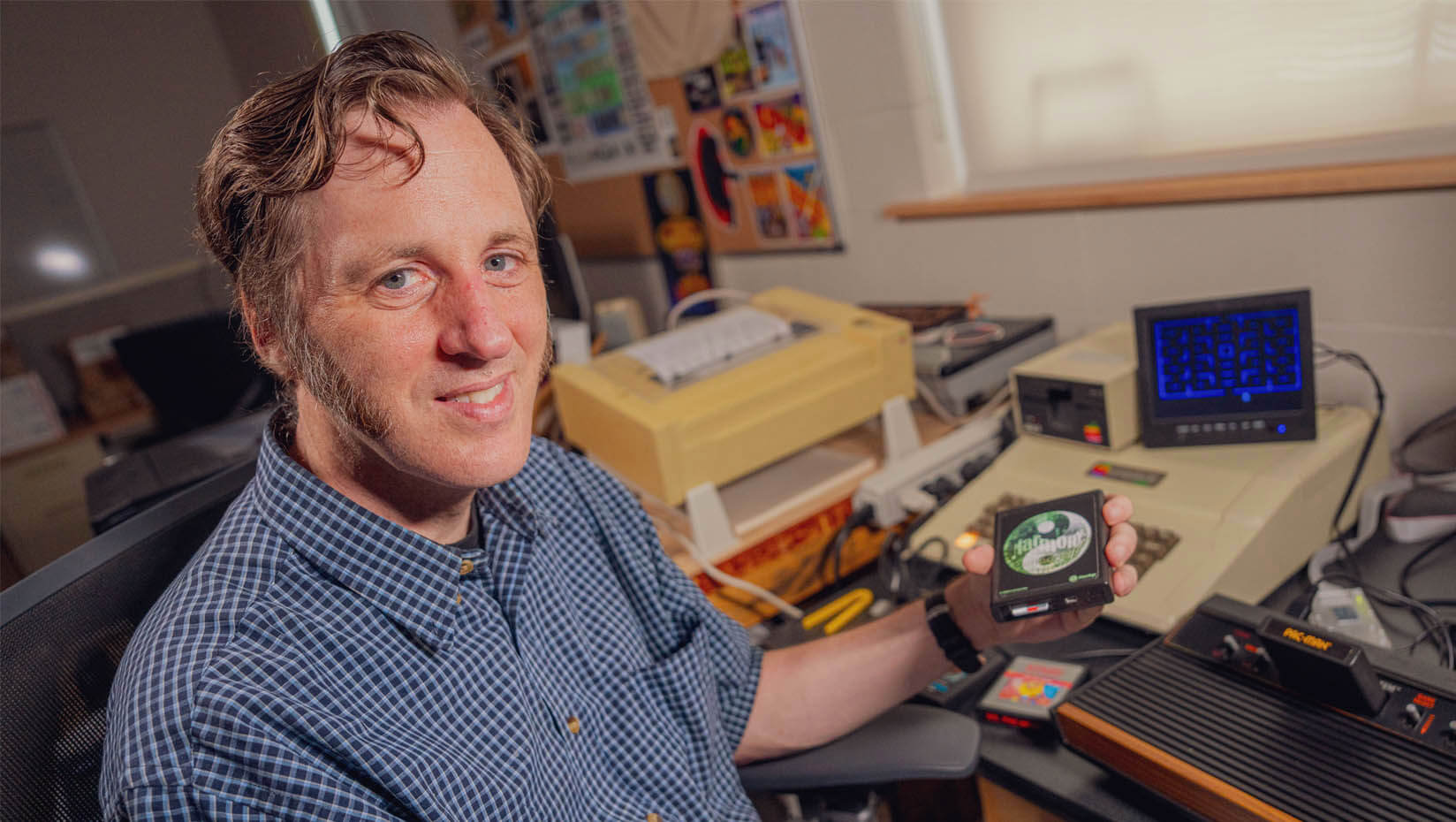

Vincent Weaver, a University of Maine associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, has a quirky hobby: “de-making” video games, or reformatting classic games onto even simpler systems than the ones they were launched on as a programming challenge. Weaver has not only amassed an online fan base for his demakes — he has also found ways to incorporate them into his curriculum for UMaine students.

Weaver has always been interested in the problem-solving elements of the most extreme computer systems, from supercomputers to microprocessors. Both systems are driven by efficiency; for small processors, efficiency ensures that their tiny batteries can last longer.

“The biggest computers and the smallest computers have a lot in common,” Weaver explains. “We have limited resources — how can we best use them to make a fast computer?”

For that reason, Weaver is also interested in the vintage computer systems that provide the foundation for the field. Because these systems were simple compared to the computers of today, the problem solving and approach to programming had to be creative and often more efficient. Weaver even rescued several old systems from a UMaine basement before they were disposed of, including an Apple II and Commodore 64.

When COVID started, Weaver was looking for a hobby that might incorporate the old computers he had amassed. He decided to try to make some of his favorite video games run on systems that were even simpler than the ones they were originally designed for, in a process known as “demaking.” Demakes try to capture all of the magic of the games with fewer graphics and processing at their disposal.

“I found it a fun side project to do,” Weaver says. “Writing a video game pushes the limits of the hardware, the software, things like that. There’s really clever stuff going on behind the scenes.”

Weaver started with a game called Kerbal Space Program, launched in 2011 and playable on Linux, OS X, Windows, PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S and Xbox One; Weaver’s demake is on the Apple II, which was designed in the 1970s. Weaver has also created partial demakes of Portal and the Monkey Island games for this system.

Recently, Weaver completed a demake Myst, a classic point-and-click adventure game from 1993 and one of the top-selling video games of all time. Myst was originally designed to be played on Macintosh systems, but Weaver’s Myst runs on the much simpler Atari 2600, released in 1977. Despite the limited computing capabilities, Weaver’s demake is recognizable frame-for-frame to the original’s graphics and gameplay.

Weaver’s detailed demakes started to catch the eyes of fellow hobbyists and programmers — including the original game designers for Myst.

“I get to talk to a lot of the creators of the games,” Weaver says. “I never thought I’d talk to these people. It’s been a fun little adventure.”

Over the past few years diving into this hobby, Weaver has realized that demakes can be a great way to introduce his engineering students to a different kind of problem solving, particularly for his EC471 class, Embedded Systems, which focuses on the tiny computers that run the technology of our everyday lives, from cellphones to microwaves.

“They’re not much more powerful than the old systems, and we still have to program them. It’s a different kind of programming. While it’s boring to think of programming a microwave, people like talking about video games and you can use the same sort of skills. It’s a good entry. Sometimes you can learn to code by doing videogames and you can apply it to other aspects of things.”

Tristan Woodrich, a 2019 alumnus of UMaine’s computer engineering program, says that Weaver makes engineering seem fun and possible for all students. Now an engineer at BAE Systems, Woodrich says Weaver inspired him to continue pursuing his own passion for collecting vintage computer systems.

“He was one of the teachers that really made it like, ‘Oh, I can actually do this,’” Woodrich says. “His knowledge is coming from passion.”

For what it’s worth, too, Woodrich says that the Myst remake shows an impressive amount of skill on Weaver’s part.

“It’s hard to get all those images into an Atari 2600. When I saw the pictures [of the Myst demake], I was like, ‘That’s a lot of detail for that system,’” Woodrich says.

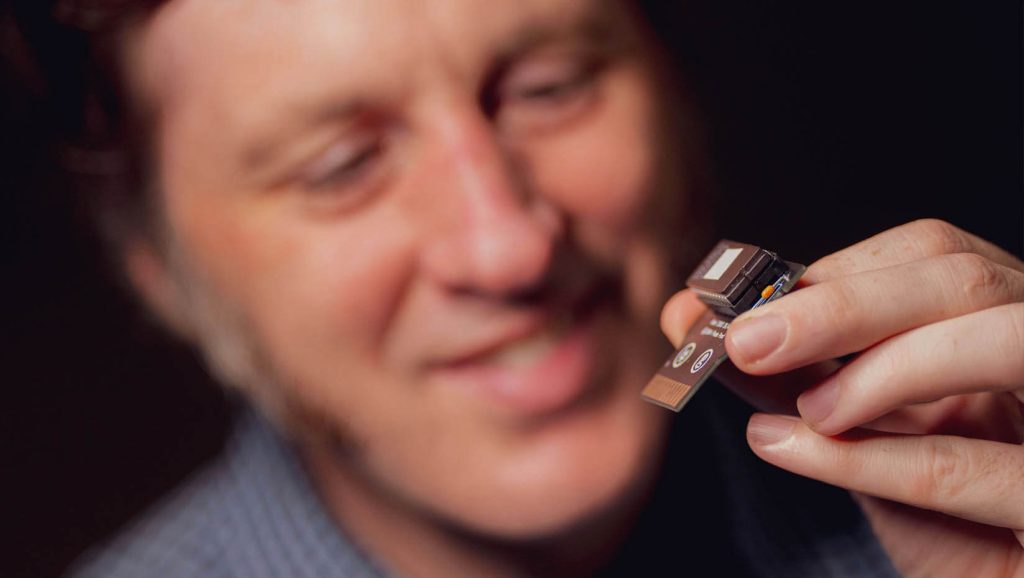

Weaver’s demakes also add to a legacy of small processors at UMaine. Chuck Peddle, a 1959 graduate of UMaine who invented the MOS Technology 6502, which revolutionized the industry for being fast and inexpensive to make, is a hero of Weaver’s. He even got to meet Peddle at a UMaine event before he died in 2019; Weaver and Woodrich displayed an exhibit of their vintage systems and processors for the event.

“There’s a history to it, and a preservation angle,” Weaver says. “Sometimes things will come up where they’re like we have to replace this 30-year-old computer and no one knows how to program it anymore. You keep it alive by remembering how to program this stuff.”

In addition to classwork for the fall, Weaver is finishing a demake of Peasant’s Quest; the original creators at Homestar Runner even sent Weaver a message saying that they are fans of his work and are looking forward to seeing the end product.

This story was written by Sam Schipani.

Contact: Marcus Wolf, marcus.wolf@maine.edu