UMaine art education students, Bangor Land Trust collaborate on edible landscape project

As part of a collaboration with the Bangor Land Trust, the Maine Humanities Council and the Clement and Linda McGillicuddy Humanities Center, art education students at the University of Maine are helping to improve food security for humans and wildlife in Maine by producing outreach materials for a project that is introducing native berry, nut, seed and fruit-producing plants to local preserves.

Through 2020 and 2021, students in associate professor of art education Constant Albertson’s AED 474/574 Topics in Art Education Courses worked on community outreach materials for the Bangor Land Trust’s Edible Landscape project, producing signage, lesson plans and illustrations related to edible plants being introduced to Bangor Land Trust preserves on the Penobscot Nation’s homeland, with the goal of increasing food sources for both wildlife and humans, encouraging consideration of our relationships to — and responsibility to care for — the places in which they live.

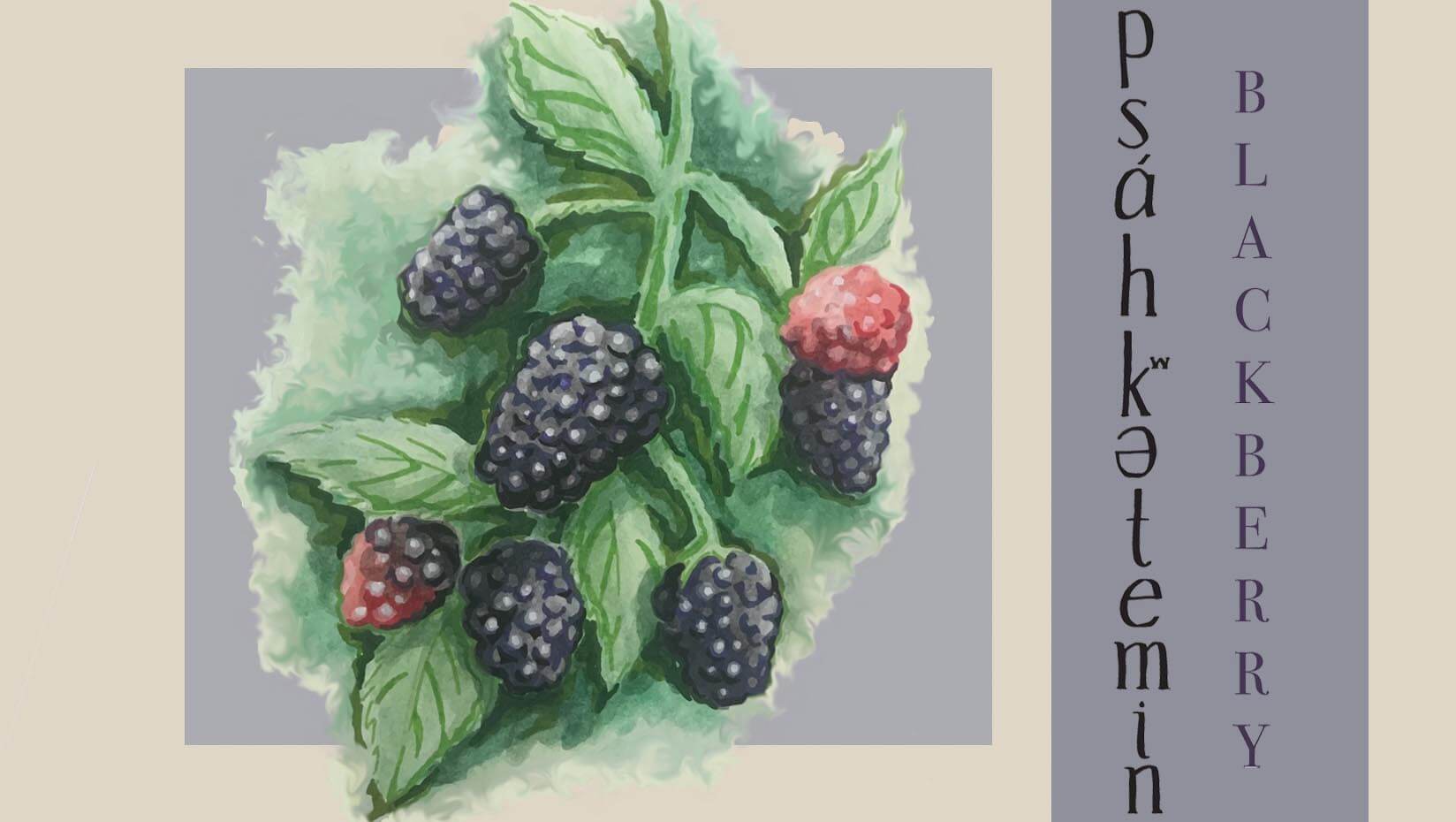

Art education students worked on original illustrations of edible plants requested by the habitat specialist and Bangor Land Trust lead project coordinator Kathy Pollard of Know Your Land Consulting. Several of these illustrations were then chosen to be digitally scanned and composed as signage with both Penobscot and English language labels that will appear around Bangor Land Trust lands. The Penobscot labels were created by hand by Penobscot elder and language keeper Carol Dana, along with the collaboration of Penobscot tribal member Ann Pollard Ranco.

The signage, which will be posted in strategic locations, is not mere decoration: it will help visitors distinguish between edible and inedible plants and fruits they might find in their journeys.

Albertson explains, “Imagery is incredibly powerful in shaping our beliefs, and consequently, our behavior. We buy goods, vote for candidates and pick up our litter largely because of the images that are in our heads about what is right and good. This makes the teaching of art highly consequential for creating the kind of society that we aspire to build.”

With this particular project, she adds, “The human community in the Bangor area suffers disproportionately from food insecurity, and the Edible Landscape will help to address that. It is an honor to assist in this endeavor, and we are grateful for this opportunity to collaborate.”

To complement their own artistic projects, which also included an educational brochure, T-shirts for volunteer planters and donors, and recipe cards explaining how visitors might make use of some of the introduced plants — such as acorn flour — the students also completed a video unit of interdisciplinary, intercultural art lessons specifically intended to address the outcomes specified in LD 295, the Maine law requiring the teaching of Wabanaki history and culture in public schools.

Originally these lessons were to be taught on-site to local middle school children, but when on-site instruction ended in the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the art education students switched gears to record lessons that would utilize common materials that children and teens might have in their homes. These lessons are available via YouTube and emphasize traditional Native American principles of sustainability now known as the Four R’s: relationship, reciprocity, respect and responsibility, principles that, the Trust points out, have guided Wabanaki values and decisions about land and water use and resource harvest for over 15,000 years.

Project lead Pollard explains that “the students in professor Albertson’s class will be able to integrate into their professional experience the capacity to teach their own students that art can be a form of activism and awareness building, as well as community service. This represents ripple effects that could potentially reach a couple generations and hundreds in number of Maine public school children.”

Moreover, she adds, “The art and informational pieces produced by the students will go out into the greater community, thereby broadening awareness for many who’ve never considered the history that led to Indigenous dispossession of lands and resources.”

Kate Westhaver, an art education and studio art double major from Nobleboro, valued the opportunity to work with stakeholders outside of the university. “I had never worked with an entity outside of myself or my professors while creating artistic products. Suddenly my class was working to provide the community with visual aids that will teach them what to eat! It was just a wonderful experience to create, edit, collaborate, and edit again, until our product was as helpful and clear as it could be.”

Westhaver, who graduated in spring 2021 and currently teaches an adaptive art at Lincoln Academy, adds “it was an extremely gratifying experience to directly work with individuals who have the best intentions for their community, and who are effecting positive change while using the impact of visual arts.”

Contact: Brian Jansen, brian.jansen@maine.edu