New book from Ballingall draws line from Plato’s Laws to our own

Ideas evolve and change. It’s the nature of learning – what we know today is more than we knew yesterday and less than we’ll know tomorrow. However, sometimes, we can look back on some of those past ideas and still learn something new.

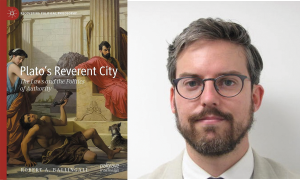

Robert Ballingall, assistant professor of political science at the University of Maine, has brought some of those past ideas into the present day, shining a new and different light on classical political philosophy.

Ballingall’s new book is Plato’s Reverent City: The Laws and the Politics of Authority, published by Palgrave Macmillan. It offers up an original interpretation of Plato’s Laws and shows the relevance of studying Plato as a way to help understand the tendencies toward cynical transgressiveness in modern societies. You can find a link to the book here.

The work of the ancient Greek philosopher has long been a subject of interest for Ballingall over the course of his academic career.

“I first became interested in the Laws as a graduate student at the University of Toronto, where I was fortunate to study Plato with one of the world’s foremost scholars of classical political philosophy, Ryan Balot,” said Ballingall. “At Toronto, Ryan taught a seminar on the Laws that was quite simply unforgettable. He helped us appreciate how this longest yet long-neglected Platonic dialogue explores questions with which every thoughtful human being must wrestle. How we should we live our lives, both individually and collectively? Should we leave it up to each person as much as possible? Or does the flourishing of each presuppose a discipline and collective action that must limit our individual discretion? Should we rule ourselves as much as possible? Or should we follow the lead of the wisest among us? How can wisdom even have authority if so few of us have the eyes to see and the ears to hear it?”

Ballingall reflected on just how prescient Plato’s work was and how the questions that it raised remain applicable to the workings of the world even many centuries later.

“The amazing thing about Plato’s Laws is how it shows the inevitability of such questions to practical politics. As frustrating and dysfunctional as politics can be, it confronts us with problems of the greatest magnitude, even if we seldom do the work to recognize as much,” he said. “On the reading of the Laws that I propose in the book, we are encouraged to consider how politics would be improved by a civic culture that fosters such recognition—that teaches citizens to stand in awe of the problems that politics must navigate.

“Indeed, the Laws suggests that there is a virtue or excellence of character disposing people to take this attitude, the closest English word for which is ‘reverence.’ At its practical best, politics nurtures and benefits from the reverence of citizens and statesmen.”

From there, Ballingall explained more deeply just how applicable Plato’s ideas are to the current political climate.

“Once I began to understand the importance of reverence to the teaching of the Laws, I was struck by how our own politics stands in dire need of it,” he said. “It’s not just that we’re exceptionally disrespectful of those with whom we disagree; it’s that we’re disrespectful of the questions or problems that lie behind our disagreements. The more contempt we have for the tasks of politics, the less respect we have for our political opponents, and for ourselves as political participants.

“There’s a paradox here: the less seriously we take what it is that we are doing, the more arrogant and complacent we become about it,” he continued. “Such attitudes are the enemies of healthy politics. If the problems at hand are trivial, then they should admit of obvious solutions, namely those that occur to me.”

The polarization of the political sphere of today is also reflected in Plato’s work; it captures the trend toward antipathy between opposing viewpoints and how that trend has developed.

“Whoever takes a different view must then seem unreasonable, the more so the more forcefully he presses his ‘absurd’ position. Contempt inspires arrogance, arrogance disdain. And it’s this disdain that is being mobilized by reckless demagogues the world over to whip their followers into frenzies of revolutionary pathos. Remarkably, then, Plato’s Laws anticipates this trend and diagnoses its origins in a cause that we otherwise have trouble describing.”

Of course, one of the joys that can come from doing a deep dive such as this one is the discovery of something unexpected. As it turns out, Plato still had a surprise or two in store for Ballingall, even after he had devoted so much time and thought to the subject. For instance, Ballingall thinks that Plato’s seeming disdain for us regular folks and our engagement with the world around us might be a touch overstated.

“Plato has a reputation for taking a dim view of ordinary people. Political life is inevitably suffused with public opinion—the opinion of the popular majority. That is why another of Plato’s dialogues, the Republic, infamously presents political life as a cave in which ordinary people are imprisoned. The opinions around which most of us organize our lives are in fact shadows, imitations of a reality from which we are for the most part cut off.

“Something that surprised me while working on the Laws is that Plato emphasizes in this other work a sense in which ordinary people can be in touch with reality despite living in the cave,” he said. “Having reverence for the questions that our moral and political opinions try to answer, we can take those opinions seriously even as we recognize something of their deficiency. We can and should be serious about our convictions even as we appreciate their “shadowiness.” Reverence allows us to love our country, for example, without blinding ourselves to its imperfections. We can revere what it is that our constitution is trying to accomplish without having to assume that it is infallible. Of course it’s not. Nothing human ever is.”

Ultimately, there’s always something more to be taken from the thoughts and ideas of the past. Even if you’ve explored them a hundred times, there’s a discovery to be made in the hundred-and-first.

“Inevitably, I would find myself confronted with new questions or with new angles on my original questions, forcing me to look at the text anew, and to delve into some other vein of the academic literature,” said Ballingall. “The dialogues are so rich and the literature that has grown up around them so vast that I could have repeated this process endlessly without losing interest in what I was doing. But at some point, I had to stop and share what I had learned.”

That stop and share resulted in Plato’s Reverent City: The Laws and the Politics of Authority. In short, Robert Ballingall thought (about) The Laws and The Laws won.