Human travel is a driving force in the spread of mosquito-borne disease

By Brian F Allan, Professor of Entomology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

[Español]

This year is shaping up to be the worst ever for mosquito-borne dengue virus. Globally, dengue cases are breaking records. In the Americas, close to 9 million human cases of dengue have been reported to the Pan American Health Organization, representing a 231% increase compared to the same period last year and a 425% increase compared to the last five years. Undoubtedly climate change is playing a major role, along with El Niño (ENSO), contributing to an early start for the development of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the most prolific vector of dengue virus on the planet. Likewise in Europe, which also is experiencing a surge in dengue cases, climate change is likely a contributing factor to the ongoing spread of the invasive Aedes albopictus mosquito, another major vector. But climate change is not the whole story, and to understand why mosquito-borne diseases are increasing in prevalence despite gains on many other fronts in public health, we must consider the contributions of human commerce and travel.

These two species of vector mosquitoes responsible for the transmission of dengue virus to humans, along with other major public health threats including chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika viruses, were not always so common. But they have a unique feature in their biology – the ability to lay “desiccation-resistant” eggs – which means that their eggs can tolerate extended periods without water. When these eggs are eventually inundated when the habitat they’re in fills with rainwater, the eggs hatch and their mosquito larvae develop. This, in combination with their proclivity to lay eggs in human-made container habitats, such as tires which get shipped all over the planet, means that they are arguably two of the most successful invasive species in human history.

Due to the global spread of these two mosquito species, the viruses they transmit to humans have been able to proliferate. All it takes to introduce one of these pathogens to a new region is for a human infected during a local outbreak to board a plane, fly to another location where one or both mosquito species has become established, and be bitten by an uninfected mosquito upon arrival. While this may sound like an improbable chain of events, this is exactly the sequence by which scientists believe Zika virus was introduced to Brazil from French Polynesia, sparking a massive outbreak in the Americas that included thousands of cases of infant microcephaly due to infections in pregnant mothers harming fetal development.

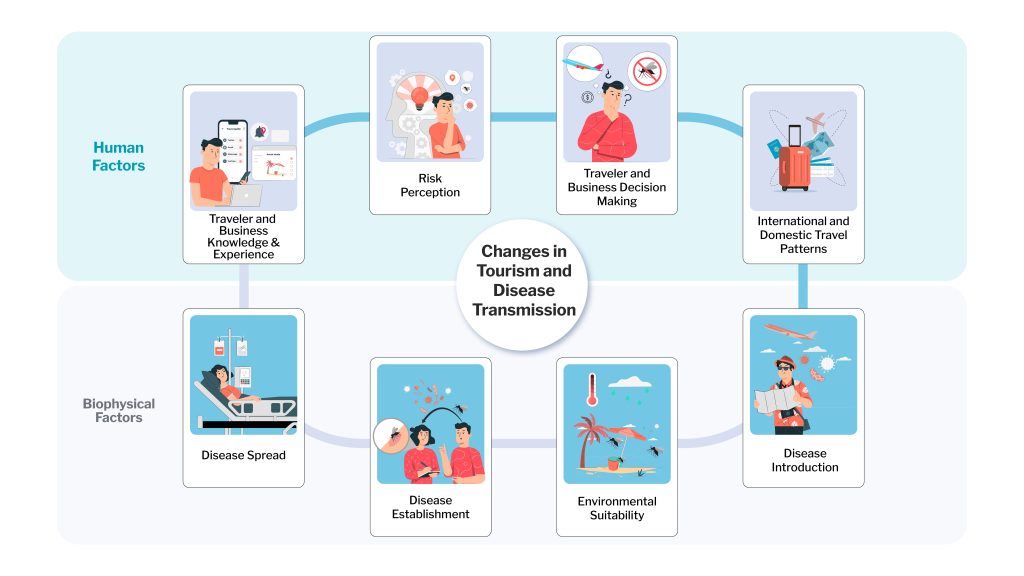

Thus it is the trifecta of commerce, human travel, and climate change that likely is to blame for the erasure of over a century of public health gains in mosquito control and mosquito-borne disease prevention. By globalizing the distributions of vector mosquitoes, human commerce has created the necessary conditions for the viruses transmitted by these mosquito species to become established. Human travel then creates the opportunity to seed new outbreaks, with the possibility of a single infected traveler introducing a new pathogen. Furthermore, the limited genetic diversity of the Zika virus at the onset of the outbreak in the Americas suggests that it was likely introduced by a single infected traveler, who may not have even been aware of their illness due to the high rate of asymptomatic cases. Adding climate change into the mix, which expands the range of environments hospitable to vector mosquitoes and creates conditions that promote early and prolonged mosquito reproduction and virus transmission, provides a clear explanation for the resurgence of mosquito-borne diseases.

Coupled Natural-Human Systems

Before we succumb to despair, it’s important to remember that we have successfully nearly eradicated several of these diseases in the past, including in many nations of the Global South. Previously, efforts were mainly concentrated on local vector control, involving large numbers of volunteers and the public to eliminate juvenile mosquito habitats, reduce mosquito entry into homes, and educate communities. A 21st-century approach must build on these strategies and expand them. This should include screening shipments for mosquito eggs (similar to current inspections for harmful agricultural pests), monitoring airline passengers for symptoms of mosquito-borne diseases, and implementing measures to mitigate the impacts of climate change. Collectively, these actions could help prevent a future marked by increased heat and illness.