Eastern Fine Paper Company Oral History Project

(You may also be interested in Women in Maine Paper Industry 1880 – 2006.)

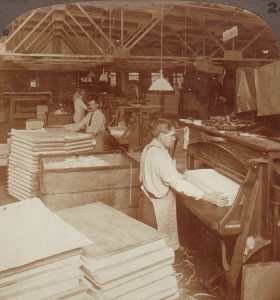

Pauleena MacDougall, Associate Director of the Maine Folklife Center, and Amy Stevens, graduate student in history, are conducting a series of oral history interviews, and collecting photographs and documents relating to the history and culture of Eastern Fine Paper in Brewer, Maine. The mill closed in January, 2003 after operating as a paper and/or lumber mill for more than a century. The project is timely because as more and more mills close, workers with specialized skills are retrained into other general service-related industries and their knowledge and heritage is in danger of disappearing.

Pauleena MacDougall, Associate Director of the Maine Folklife Center, and Amy Stevens, graduate student in history, are conducting a series of oral history interviews, and collecting photographs and documents relating to the history and culture of Eastern Fine Paper in Brewer, Maine. The mill closed in January, 2003 after operating as a paper and/or lumber mill for more than a century. The project is timely because as more and more mills close, workers with specialized skills are retrained into other general service-related industries and their knowledge and heritage is in danger of disappearing.

There has been a steady attrition of paper mills and papermaking jobs in Maine for the last thirty years, just as elsewhere in America a decreasing number of workers are employed in manufacturing. This process is markedly similar to the historical decline of farming and logging, in which a progressively smaller number of people produced an expanding volume of goods. However, it differs in that the paper companies have moved their operations to countries in South America and Asia where labor is inexpensive. As a result, unionized factory workers are forced into lower-paying, non-unionized service sector jobs, and income disparities increase – as has happened here in Maine.

Our approach is both historical and anthropological.

History

Maine was competitive in nation-wide lumber markets before 1880, but a new forest industry grew in the latter part of the 19th century: pulp and paper production. The paper industry began to expand in 1827 when the paper machine known as the Fourdinier was brought to New England, creating paper in a continuous-flow process for the first time.

Maine was competitive in nation-wide lumber markets before 1880, but a new forest industry grew in the latter part of the 19th century: pulp and paper production. The paper industry began to expand in 1827 when the paper machine known as the Fourdinier was brought to New England, creating paper in a continuous-flow process for the first time.

This new industry required large amounts of capital. Using funds acquired from the lumber trade in Boston and New York, capitalists built mills on the lower Penobscot, Kennebec, and Androscoggin Rivers in the 1880s. The state’s abundant woodlands and waterways provided cheap log transportation and hydroelectric power necessary for pulp and paper production, and soon, entire new cities in the Maine wilderness were created to serve the industry’s needs. Not only was the latter part of the nineteenth century the most active period of industrial expansion, but by the time the Eastern Fine Paper mill (at that time the Ayer mill) was built in the 1880s, Maine’s poplar and spruce trees had become the most useful species for paper making.

Papermaking drew new investments into the state, and a diverse array of products, from newspapers to paper plates, was manufactured. In 1885 Maine had 12 pulp and 9 paper mills. By 1906, the industry had grown to 109 mills.

By 1900 the industry had dominance over Maine’s forests, consuming nearly half the annual cut of timber in the state. Paper production increased in the 1950s, accounting for 80 percent of the forest’s bounty. Millinocket’s Great Northern mill was the largest producer, with a thousand tons per day, and a new facility was built in East Millinocket that nearly matched Great Northern’s output. Other giants in the industry were Oxford Paper in Rumford, Fraser in Madawaska, S.D. Warren in Westbrook, International in Jay, and Scott in Winslow. Together with Brewer’s Eastern Fine Paper mill, they made Maine the eighth ranking paper-making state in the nation. By 1970, one quarter of Maine’s manufacturing workforce was employed in the paper industry.

But that soon changed. According to forester and historian Lloyd Irland, by 1999, only 17 pulp and/or paper mills remained, including those in the towns of Millinocket and East Millinocket, Old Town, Brewer, located along the Penobscot River. Maine mills experienced competitive pressure from mills in the southern United States, Canada, and other countries. So despite the paper industry’s strong record of growth throughout the twentieth century, layoffs and mill closings have occurred in several Maine towns. As a result, paper mill workers are at risk. While a few workers have found jobs at other mills, many are no longer employed or have been forced to seek out employment in other sectors. As these workers move into other areas of the economy, their traditional knowledge is lost. Because paper has been such an important part of Maine’s culture and its history, it is imperative that we undertake a study of the paper industry.

Anthropology

A branch of anthropology, folklore seeks to document the traditions of work in a given trade. From a cultural point of view, work is central to people’s lives. Work helps to define individual identity. Human beings relate occupation to race and ethnicity, gender, region, and religion.

A branch of anthropology, folklore seeks to document the traditions of work in a given trade. From a cultural point of view, work is central to people’s lives. Work helps to define individual identity. Human beings relate occupation to race and ethnicity, gender, region, and religion.

Benjamin A. Botkin first coined the term “industrial folklore” in the 1930s, after which it came to be known variously as: occupational folklore, workers’ culture, the anthropology of work, labor’s heritage, and occupational folklife. Whatever the name, the study encompasses job technique, customary practice, verbal art, and ideological causes.

Folklorists such as Phillips Barry, Fannie Eckstorm, and Mary Smyth recorded logging disasters preserved in the ballads and folksongs of the Maine lumber woods. Horace Beck and Wayland Hand collected tales and legends of disasters in maritime and mining occupations. And Ben Botkin, Archie Green, George Korson, and Pat Mullen have all presented worker’s expressions of the danger of industrial work.

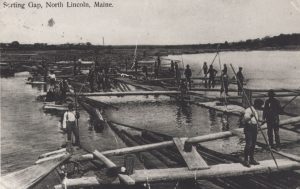

Since the 1960s, Edward D. “Sandy” Ives, founder of the Maine Folklife Center, has built the preeminent collection of folk culture from Maine and Maritime Canada’s lumbering occupation. At first interested primarily in songs, Ives later collected and presented the most comprehensive description of lumbering and river driving in his study of how lumber from the northern Maine woods made its way to lumber mills on the Penobscot River. He documented the skills, the processes, the stories, and the details of workers’ lives as the occupation ended, but before workers knowledgeable about the industry passed on. These oral histories of lumbering and river driving in our collection provide a solid foundation for our current papermaking research.

Ives and others have demonstrated how formal knowledge exists side by side in the workplace with abundant lore, such as wordplay, arcane nomenclature, raw jests, admonitory tales, outlandish boasts, bawdy humor, and nicknames. Workers symbolically “buy back” dignity or identity with pranks and jests and other folkloric forms. One thing we hope to find out through the interview process is how expressive learning such as this shapes notions of identity and reality. Workers’ folklore and work culture may lead to a better understanding of labor economics and/or industrial relations.

Linguistic expressions also provide an understanding of identity and attitudes: towards business, other workers, management, or unions. Numerous questions may be answered by the present research. Tradition is innately conservative – labor unions are liberal. How do these ideas intersect?

Linguistic expressions also provide an understanding of identity and attitudes: towards business, other workers, management, or unions. Numerous questions may be answered by the present research. Tradition is innately conservative – labor unions are liberal. How do these ideas intersect?

In addition, how has the mill closing affected the community? After industrial dislocation, workers face not only economic hardship but also the traumatic loss of heritage and identity. Initial interviews underscore this response. Most of the workers interviewed to date have expressed a great sense of sadness and loss, referring to the workplace as “family,” and the mill’s shut-down “like a divorce.”

For additional reading:

Women in Maine Paper Industry 1880 – 2006 / University of Maine

Applebaum, Herbert. 1981. Royal Blue: The Culture of Construction Workers. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Botkin, Benjamin. 1949. “Industrial Lore.” In Maria Leach, ed., Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 521-22.

Clarke, John et al. 1980. Working-Class Culture. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Condon, Richard H. 1995. “People and Economy.” In Richard W., Judd et al, eds., Maine: The Pine Tree State from Prehistory to the Present. Orono: University of Maine Press, 535.

Green, Archie. 1960 “American Laborlore: Its Meanings and Uses.” Industrial Relations 4 (February): 51-68.

Hand, Wayland. 1941 “Folklore from Utah’s Silver Mining Camps.” Journal of American Folklore 54: 132-61.

Irland, Lloyd. 2004. “Maine’s Forest Industry: From One Era to Another.” In Richard Barringer, ed., Changing Maine: 1960-2010. Gardiner, Me.: Tilbury House; Portland, Me.: Muskie School of Public Service, University of Southern Maine, 363-387.

Ives, Edward D. 1985. “The Teamster in Jack MacDonald’s Crew.” In Alan Jabbour and James Hardin, Folklife Annual. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, The American Folklife Center, 74-85.

Ives, Edward D. 1976. “Argyle Boom.” Northeast Folklore vol. XVII, Northeast Folklore Society, University of Maine, Orono.

Judd, Richard. 1995. “The Pulp and Paper Industry, 1865-1930.” In Richard W., Judd et al, eds., Maine: The Pine Tree State from Prehistory to the Present. Orono: University of Maine Press, 426-431.

McCarl, Robert S. 1988. “Accident Narratives: Self Protection in the Workplace.” New York Folklore vol. XIV, Nos. 1-2.