What is eDNA?

As organisms transverse their environs they behind a trace of its genetic information throughout actions as simple as touching the air. The genetic material they shed is commonly referred to as environmental DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) or eDNA. Scientists can collect this eDNA from water, air, and soil samples and the sampling method is relatively non intrusive. This allows scientists to obtain information about a species like presence and abundance. This can be paired with other methods to study biodiversity of an environment or species range shifts. Sample collection can be as easy as collecting water in a plastic water bottle.

What Questions can eDNA Help Answer?

There are many eDNA projects happening across Maine exploring who is in our waters, the spread of disease, historical species presence and more!

Tracking Shark Migration

Kyle Oliveira, a Maine-eDNA graduate student, is using eDNA to study white sharks. With the Gulf of Maine warming, more sharks are making their way north from Cape Cod. eDNA helps Kyle detect the sharks even if we can’t see them in the water. This data can be leveraged to build models that will help people know when sharks are likely to be in certain places. This information can be used for further research, public safety, and more.

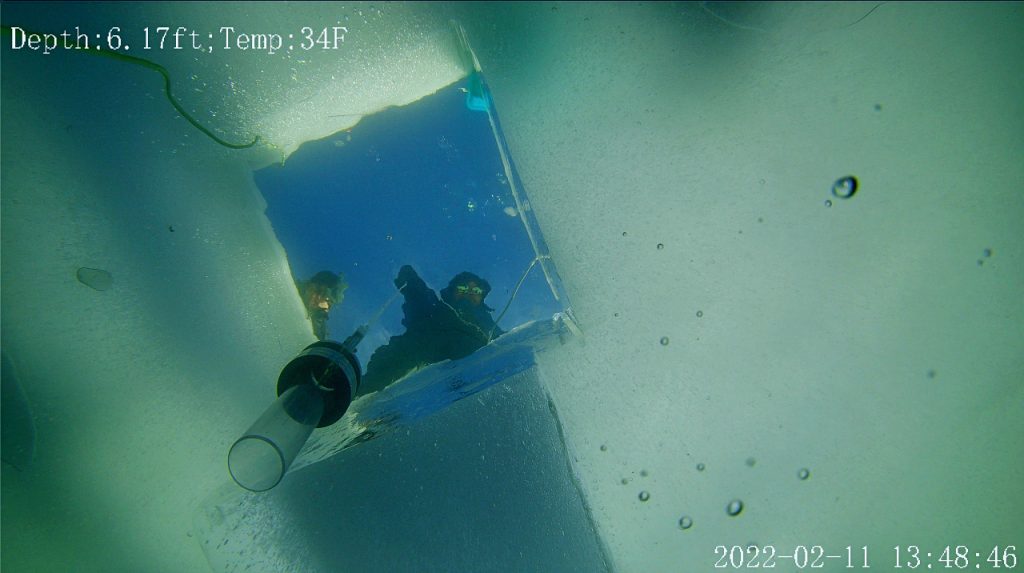

Detecting and Quantifying Scallops

Phoebe Jekielek, Maine-eDNA Ph.D. Candidate and Hurricane Island Lead Scientist, uses eDNA to study scallop populations. Scallops are hard to detect and quantify without pulling them out of the water or diving. Phoebe is taking samples throughout the water column over active scallop beds to help improve eDNA as a tool to detect the species. If successful, aquaculturalists will be able to locate and quantify beds easily from the surface.

Understanding Disease Spread

Dr. Allison Gardner, Associate Professor of Medical Entomology at UMaine, uses eDNA to detect mosquitoes, a disease vector, in their aquatic habitat. The more mosquitoes there are in one place the more likely humans catch disease. Dr. Gardner and her team hope to develop tools that allow them to detect the presence and quantity of mosquitoes to help protect humans from disease.

Investigating Algal Blooms

The Wolfeboro Waters town committee noticed new algal blooms in the water. Concerned about the presence of a potentially harmful cyanobacterium a group of community members turned to eDNA for help. The group funded the purchase of a portable quantitative PCR machine which allowed them to genotype eDNA samples. Within a week of sampling a new bloom the group was able to identify that bloom as Dolichospermum.

Historical Species Presence

Grayson Huston, a Maine-eDNA graduate student, is looking at historical alewife populations in Maine lakes. Many eDNA researchers are looking at current populations but it is also important to understand who used to be in certain environments. By taking cores from the bottom of lakes, Grayson uses eDNA to detect whether alewife were present hundreds of years ago. This can help better target alewife recovery efforts and potentially work for other species as well.

Quantifying Carbon Storage

Heather Richard, a Maine-eDNA graduate student, uses eDNA to better understand how Maine’s marshlands function as carbon sinks. Marshes are capable of storing a lot of carbon but building roads and other infrastructure through them could have deleterious effects on their ability to store carbon. Heather uses metabarcoding to look at the hard to study microbial and fungal communities present in these marshlands. These microbes play a big role in storing carbon and the presence or absence of certain microbes could help measure the marsh’s ability to store carbon.

To learn more about how eDNA in a water sample is translated to a species list check out the videos produced with Maine-eDNA researchers on the lab and bioinformatics processes.